In Bascom Global Internet v. AT&T Mobility LLC, Bascom Global sued for infringement of US Patent No. 5,987,606, titled "Method And System For Content Filtering Information Retrieved From An Internet Computer Network," November 16, 1999 (the '606 patent). The defendant moved to dismiss the complaint under Rule 12(b)(6), and the motion for dismissal was granted on the ground that the claims of the '606 patent are ineligible as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101. In what could become a highly impactful decision, the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the district court's order dismissing the complaint.

This is only the third time that the Federal Circuit has held software claims patent eligible since the Supreme Court's Alice decision (the first two were DDR and Enfish). Although these three cases have some common themes, they provide different paths to patent eligibility. Of the three decisions, Bascom may be the most generally applicable. Judge Chen wrote for the court, joined by Judge O'Malley. Judge Newman concurred, writing separately on her views of how to harmonize litigation on patentability and eligibility.

Background

The '606 patent describes and claims a system for filtering Internet content. The patent describes its filtering system as a novel advance over prior art computer filters, in that no one had previously provided customized filters at a remote server. The claimed filtering system is located on a remote ISP server that associates each network account with (1) one or more filtering schemes and (2) at least one set of filtering elements from a plurality of sets of filtering elements, thereby allowing individual network accounts to customize the filtering of Internet traffic associated with the account. For example, one filtering scheme could be a word-screening type filtering scheme, and one set of filtering elements (from a plurality of sets) could be a master list of disallowed words or phrases together with an individual list of words, phrases or rules.

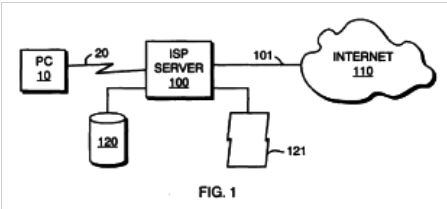

Figure 1 of the patent is reproduced below. This is described as a single-user configuration embodying the invention. In the single-user configuration, local client 10 is connected to ISP server 100. The connection 20 is described as typically being a dial-up asynchronous telephone line but could be any of a number of known means, such as a cable connection or a continuous direct connection. The ISP server is described as including at least one filter scheme 121 and a database 120 of a plurality of sets of filtering elements associated with individual end users.

Claim 1 is an example of the claims at issue:

- A content filtering system for filtering content retrieved from an Internet computer network by individual controlled access network accounts, said filtering system comprising:

a local client computer generating network access requests for said individual controlled access network accounts;

at least one filtering scheme;

a plurality of sets of logical filtering elements;

and a remote ISP server coupled to said client computer and said Internet computer network, said ISP server associating each said network account to at least one filtering scheme and at least one set of filtering elements, said ISP server further receiving said network access requests from said client computer and executing said associated filtering scheme utilizing said associated set of logical filtering elements.

In its motion to dismiss, the defendant applied the Supreme Court's decision in Alice[1] and argued that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of "filtering content," "filtering Internet content" or "determining who gets to see what," each of which is a well-known "method of organizing human activity" like the intermediated settlement concept that was held to be an abstract idea in Alice. Bascom responded by arguing that the claims are not directed to an abstract idea because they address a problem arising in the realm of computer networks, and provide a solution entirely rooted in computer technology, similar to the claims at issue in DDR Holdings.[2]

Bascom characterized the recent Supreme Court and Federal Circuit decisions invalidating claims under § 101 as focusing on claims that are directed to a longstanding fundamental practice that exists independent of computer technology, and asserted that its claims are different because filtering Internet content was not longstanding or fundamental at the time of the invention and is not independent of the Internet. In addition, Bascom argued that, even if the claims are directed to an abstract idea, the inventive concept is found in the ordered combination of the limitations: a "special ISP server that receives requests for Internet content, which the ISP server then associates with a particular user and a particular filtering scheme and elements."

The district court found that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of "filtering content" because "content provided on the Internet is not fundamentally different from content observed, read, and interacted with through other mediums like books, magazines, television, or movies." In its search for an "inventive concept," the district court first determined that no individual limitation was inventive because each limitation, in isolation, was a well-known, generic computer component or a standard filtering mechanism. The district court then determined that the limitations in combination were not inventive either because "[f]iltering software, apparently composed of filtering schemes and filtering elements, was well-known in the prior art" and "using ISP servers to filter content was well-known to practitioners." The district court also noted that the absence of specific structure for the generic computer components raised the likelihood that such claims could preempt every filtering scheme under the sun.

Federal Circuit Opinion

In the Opinion entered by Judge Chen, the court commented that software-related patents have been found eligible under both steps of the Alice two-step test. The court found that the claims were not sufficiently limited to avoid the "abstract idea" moniker under step one, but were nonetheless eligible under step two.

Step 1

Under step one, the court noted that a particular improvement to a database system patent was deemed eligible under step one in Enfish,[3] a case in which the court found claim language reciting the invention's specific improvements to help its determination in step one that the invention was directed to those specific improvements in computer technology.

The court also recognized that, in other cases involving computer-related claims, there may be close calls about how to characterize what the claims are directed to. In such cases, an analysis of whether there are arguably concrete improvements in the recited computer technology could take place under step two. That is, some inventions' basic thrust might more easily be understood as directed to an abstract idea, but under step two it might become clear that the specific improvements in the recited computer technology go beyond well-understood, routine, conventional activities and render the invention patent-eligible. The court took this step-two path in DDR in stating, "When the limitations of the . . . claims are taken together as an ordered combination, the claims recite an invention that is not merely the routine or conventional use of the Internet."[4]

The court noted that claim 1 of the '606 patent is directed to a content filtering system for filtering content retrieved from an Internet computer network, and claim 22 similarly is directed to an ISP server for filtering content. The court also noted that the specification reinforces the Internet-centric nature of the invention by describing the invention as relating "generally to a method and system for filtering Internet content." Bascom had argued that the claims are directed to something narrower than the concept of "filtering," i.e., the specific implementation of filtering content set forth in the claim limitations. Specifically, Bascom argued that claim 1 is directed to the more specific problem of providing Internet-content filtering in a manner that can be customized for the person attempting to access such content while avoiding the need for local servers or computers to perform such filtering and while being less susceptible to circumvention by the user, and claim 23 is directed to the particular problem of structuring a filtering scheme not just to be effective but also to make user-level customization administrable as users are added. The court recognized that it sometimes incorporates claim limitations into its articulation of the idea to which a claim is directed, citing Enfish, 2016 WL 2756255 at *6 (relying on a step of an algorithm corresponding to a means-plus-function limitation in defining the idea of a claim for step-one purposes). The court distinguished this case from Enfish, stating that the claims in Enfish were unambiguously directed to an improvement in computer capabilities whereas here the claims and their specific limitations "do not readily lend themselves to a step-one finding that they are directed to a non-abstract idea." The court thus deferred consideration of the specific claim limitations' narrowing effect for step two and the search for an "inventive concept."

Step 2

The court noted that the "inventive concept" may arise in one or more of the individual claim limitations or in the ordered combination of the limitations, and that an inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention must be significantly more than the abstract idea itself, and cannot simply be an instruction to implement or apply the abstract idea on a computer.

The district court had taken each limitation individually and noted that the claimed "local client computer," "remote ISP server," "Internet computer network" and "controlled access network accounts" were well-known generic computer components. The district court also analyzed the limitations collectively, and held that filtering software, composed of filtering schemes and filtering elements, and using ISP servers to filter content, were well-known at the time the application was filed. The district court thus concluded that the limitations, considered individually or as an ordered combination, are no more than routine additional steps involving generic computer components and the Internet, which interact in well-known ways to accomplish the abstract idea of filtering Internet content.

Inventive Concept

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the limitations of the claims, taken individually, recite generic computer, network and Internet components, none of which is inventive by itself. However, the court disagreed with the district court's analysis of the ordered combination of limitations. The court characterized the district court's analysis as being similar to an obviousness analysis under 35 U.S.C. § 103, except lacking an explanation of a reason to combine the limitations as claimed. The court said that the inventive concept inquiry requires more than recognizing that each claim element, by itself, was known in the art. According to the court, an inventive concept can be found in the nonconventional and non-generic arrangement of known, conventional pieces. The court characterized the inventive concept described and claimed in the '606 patent as the installation of a filtering tool at a specific location, remote from the end users, with customizable filtering features specific to each end user, which allegedly gives the filtering tool both the benefits of a filter on a local computer and the benefits of a filter on the ISP server. Based on the limited record before it, the court held that this specific method of filtering Internet content cannot be said, as a matter of law, to have been conventional or generic.

The court went on to say that the claims do not merely recite the abstract idea of filtering content along with the requirement to perform it on the Internet, and they do not preempt all ways of filtering content on the Internet. According to the court, the claims instead recite a specific, discrete implementation of the abstract idea of filtering content. The court noted that filtering content on the Internet was already a known concept, and the patent describes how its particular arrangement of elements is a technical improvement over prior art ways of filtering such content.[5]

The court also noted that its recent case law on step two of the Alice test supports the patent-eligibility of Bascom's claims. The court favorably compared the present case to DDR, noting that it held that DDR's patent claimed a technical solution to a problem unique to the Internet – websites instantly losing views upon the click of a link, which would send the viewer across cyberspace to another company's website. The court said that the claimed invention in DDR solved the problem in a particular, technical way by sending the viewer to a hybrid webpage that combined visual elements of the first website with the desired content from the second website that the viewer wished to access. The court said that DDR's patent was engineered in the context of retaining potential customers, and claimed a technical way to satisfy an existing problem for website hosts and viewers. Similarly, the court noted, the invention in the '606 patent is engineered in the context of filtering content, and the '606 patent claims a technology-based solution to filter content on the Internet that overcomes existing problems with other Internet filtering systems. The court characterized Bascom's solution, taking a prior art filter solution (one-size-fits-all filter at the ISP server) and making it more dynamic and efficient (providing individualized filtering at the ISP server), as representing a software-based invention that improves the performance of the computer system itself.

Conclusion

This case shows the value of being able to describe the invention as a technological solution to a problem rooted in technology. Moreover, even where the claimed invention is a combination of known elements, patent-eligibility can be based on a showing that the claims recite an ordered combination or configuration of elements designed to solve the specific technological problem. Structural claim limitations can also be helpful in avoiding overbreadth and the risk of preemption.

In this case, the court saw an "inventive concept" in the allegedly novel configuration of known elements. The court worked from the DDR framework on the second Alice step (familiar to Judge Chen, since he also wrote DDR), viewing the claims here as a technology-based solution. It seems safe to observe from Bascom (as well as Enfish and DDR) that, on one hand, the court is looking for a claim rooted in technology, but on the other hand the court is looking for a claim that is narrow in some respects so as to avoid "preemption," a specter which continues to haunt the patent law. The court seems favorably disposed toward claims offering a particular way of implementing a general idea. The breadth/preemption idea is always woven into the background of § 101 cases, but the court has not done a good job of explaining the test for overbreadth in § 101. To some degree, these considerations rise and fall together – a narrower claim is going to look more like a specific technological solution.

One way to read the three cases finding eligibility is that in "clear" cases like Enfish, the analysis can end at step one. But Enfish's claim had the benefit of the means-plus-function construction incorporating a particular algorithm. In more difficult cases like DDR or Bascom, the step two analysis is necessary – even if there is not a clearly established abstract idea.

Footnotes

[1] Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank

International, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014)

[2] DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 773 F.3d 1245

(Fed. Cir. 2014)

[3] Enfish LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 2016 WL 2756255, at *8

(Fed. Cir. May 12, 2016)

[4] DDR, 773 F.3d at 1259

[5] According to the court, prior art filters were either

susceptible to hacking and dependent on local hardware and

software, or confined to an inflexible one size-fits-all scheme.

The court accepted Bascom's assertion that the inventors

recognized there could be a filter implementation versatile enough

that it could be adapted to many different users' preferences

while also installed remotely in a single location. Thus, construed

in favor of the non-movant – Bascom – the claims were

deemed to be more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the

abstract idea, but rather could be read to improve an existing

technological process.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.