In July 2014 AbbVie Inc. and Shire Plc announced a $54.8 billion merger deal that would have made AbbVie the largest U.S. company to move its legal residence, though not its operations, abroad in order to lower its tax rate in 2016 from 22% to 13% (i.e., a corporate inversion). At the time, the U.S. government was discussing how to curb such corporate inversions. Between 2012 and 2014, 20 U.S.-registered companies entered into agreements that would result in a shift of their legal address abroad to lower their tax. Two months later, the Treasury Department announced rules to limit the financial benefits of corporate inversions. Within a month of the Treasury announcement, AbbVie's board recommended that shareholders vote against the takeover of Shire, saying the change in the tax rules would undermine the reasons for entering into the deal.

Given the political environment opposed to corporate inversions at the time the deal was negotiated, Shire had sought protection in case the United States passed legislation putting the deal at risk. The agreement called for AbbVie to pay Shire a termination fee (also known as a "breakup fee") of 3% of the deal's value, or about $1.6 billion, if the deal was not consummated. Merger agreements often contain provisions for the payment of a termination fee by the party terminating the agreement, as a way to compensate the other party for costs incurred should the deal not be consummated. Termination fees range in amount, depending on the size of the transaction and the reason for termination, but are typically significant in whole-dollar terms.

The tax treatment of termination fees, both from the standpoint of business expenses versus capital expense and the character of the fees (i.e., ordinary or capital), is a significant issue for taxpayers. The primary effect of treating a termination payment as either an ordinary business expense or a capital expenditure concerns the timing of the taxpayer's cost recovery: while business expenses are currently deductible, a capital expenditure usually is amortized and depreciated over the life of the relevant asset, or, where no specific asset or useful life can be ascertained, is deducted upon dissolution of the enterprise. The effect of characterizing a termination payment as ordinary or capital primarily affects the benefit of a loss to the taxpayer: capital losses are not deductible as ordinary expenses and generally are only allowed to offset capital gains. It was reported that if AbbVie were able to deduct the breakup fee as an ordinary expense, rather than being required to capitalize the fee, it would reduce AbbVie's tax liability by approximately $650 million.

The tax treatment of termination fees, both in terms of deductibility or capitalization of the expense of the fee and the character of the fee as either ordinary or capital, has been the subject of past litigation and Internal Revenue Service (the "Service") guidance. Treasury Regulations under Code section 263 provide that the costs of terminating a transaction are normally deductible at the time of termination. However, the payer of a breakup fee is required to capitalize the fee if the payer is terminating the transaction in order to enter into another transaction.

Prior to 2016, the Service issued guidance [See TAM 200438038 and PLR 200823012] where it treated termination fees as liquidated damages, and thus ordinary income, arguably because the taxpayer had not sold, exchanged or transferred any capital asset. The Service noted that provisions of the tax law, namely Code Section 1234A, which provide that gain or loss attributable to the termination of a right or obligation with respect to a capital asset will be treated as gain or loss from the sale of a capital asset did not apply to the termination fees received. Thus, unless the termination of a merger agreement subsequently facilitated a second mutually exclusive transaction, the breakup fees were treated by the Service as ordinary income and eligible for deduction.

However, in recent taxpayer specific guidance released in September and October of 2016 [See CCA 201642035 and FAA 20163701F], the Service reversed its position and provided that capital asset provisions (again, Code Section 1234A) of the tax law apply to termination fees pursuant to certain merger agreements. The guidance involved the acquisition of stock in a reorganization. In the new guidance, the Service's view is that the target's stock would have been a capital asset in the hands of an acquirer had the deal been completed and, therefore, the breakup fee relates to a contractual right and obligation concerning a capital asset (the right and obligation to acquire target stock). Thus, any gain or loss realized by a taxpayer on the termination of the merger agreement would be capital in nature. The importance the Service placed upon the fact that the termination fee was paid under a contract to purchase the stock of a target may imply that the result would be different if the fee is not paid under an executed contract or where the contract is for the acquisition of something other than a capital asset (e.g., operating business assets).

The new guidance may have resulted from the 2014 proposed merger of AbbVie and Shire, which involved a mix of cash and stock consideration and, as discussed above, would have resulted in a corporate inversion of AbbVie if completed. The facts in one piece of guidance are similar to those of the failed AbbVie merger, which resulted in AbbVie being required to pay a $1.6 billion breakup fee when it withdrew from the deal. Given the amount at stake to AbbVie, there is likely to be litigation concerning the tax treatment of the breakup fee if it was, indeed, the subject of this guidance.

This change in the Service's position could result in a taxpayer incurring a capital loss upon payment, which limits the benefits of a loss to the taxpayer. Capital losses are not deductible as ordinary expenses and usually are only allowed to offset capital gains. However, the receipt of a termination fee could result in capital gain, which may allow it to take advantage of existing capital losses that might otherwise expire unused or to be taxed at favorable capital gain rates if ultimately passed through to an individual investor. Thus, payers and recipients of breakup fees are likely to argue for opposing treatment of such fees.

The treatment of breakup fees is likely to hinge on the form of the merger transaction and is not always clear. The following examples illustrate this point.

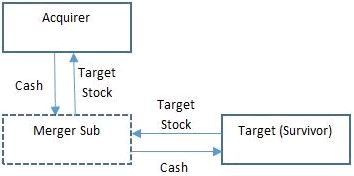

Reverse Subsidiary Merger (Cash)

In a reverse subsidiary merger for cash, Acquirer's transitory Merger Sub will merge into Target, with Target surviving as a subsidiary of Acquirer. Target's shareholders will receive cash in exchange for their Target stock. If Acquirer subsequently abandons the deal and pays a breakup fee to Target, Acquirer's loss will likely be treated as capital because it is attributable to a capital asset: Target's stock. However the treatment of Target's receipt of the breakup fee is not as clear. A merger agreement generally contains rights and obligations with respect to different properties, including cash consideration, the target's stock, stock of a merger subsidiary, and the assets of the target. In this example, neither the cash nor Target's own stock would be capital assets in Target's hands, but certain of Target's assets may be capital assets. No IRS guidance has addressed the characterization of a breakup fee with respect to capital assets of a target. Thus, arguments can be made for both ordinary and capital treatment, depending on Target's asset composition.

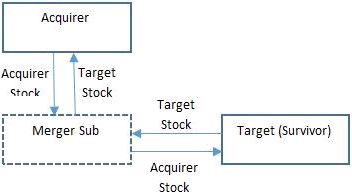

Reverse Subsidiary Merger (Stock for Stock)

In a reverse subsidiary merger for stock, Acquirer's transitory Merger Sub will merge into Target, with Target surviving as a subsidiary of Acquirer. Target's shareholders will receive Acquirer stock in exchange for their Target stock. If Acquirer subsequently abandons the deal and pays a breakup fee to Target, Acquirer's loss will likely be treated as capital because it is attributable to a capital asset: Target's stock. Similarly, since the merger agreement also contains rights and obligations with respect to Purchaser's stock, which would be a capital asset in Target's hands, then Target's receipt of the breakup fee should constitute capital gain.

Forward Subsidiary Merger

As another example, consider a forward merger where Target will merge into Acquirer's newly-formed Merger Sub, with Merger Sub surviving as a subsidiary of Acquirer. Target's shareholders will receive cash in exchange for their Target shares. For U.S. federal income tax purposes, Target is treated as transferring all of its assets to the surviving Merger Sub. This presents a stronger case for looking at the target's assets to determine whether capital asset treatment should apply. An argument could be made that the breakup fee should be allocated between ordinary income and capital gain or loss based on the relative values of the target's capital and non-capital assets. However, breakup fees generally apply to the merger agreement as a whole, rather than the independent rights and obligations contained in the agreement. This could require Target's gain or loss to be characterized as capital if the target held any capital assets. The same allocation issue could arise in a merger involving a mix of cash and stock consideration. Again, no IRS guidance has addressed the characterization of a breakup fee with respect to the capital assets of a target.

Apart from the Treasury Regulations, the guidance issued by the Service is not binding on taxpayers but is reflective of the position the Service is likely to take. Absent further guidance from the Service, legislation, or subsequent litigation, the tax treatment of breakup fees is likely to remain unclear. Parties involved in M&A transactions should carefully evaluate the likely tax consequences before agreeing to pay termination fees.

IRS Reverses Its Position Regarding The Treatment Of Merger Breakup Fees

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.