In Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v. Hospira, Inc.,1 the Federal Circuit affirmed the lower court's ruling that the asserted claims of Merck's U.S. Patent No. 6,486,150 (the '150 patent) were obvious despite evidence of commercial success and copying by others. Concerned that the majority's opinion constituted a shortcut around a proper Graham analysis, Judge Newman dissented and highlighted the court's inconsistent application of secondary considerations of nonobviousness in the context of establishing a prima facie case of obviousness. The decision is also noteworthy for its clarification of the so-called blocking patent and the effect of such a patent on evidence of commercial success.

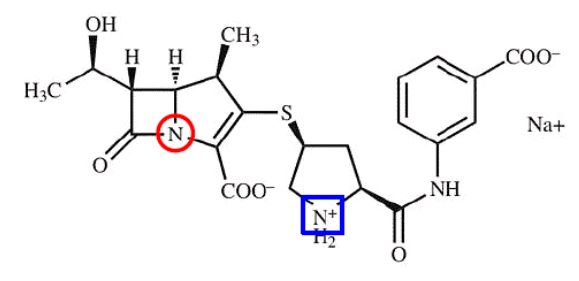

Ertapenem is an antibiotic known to be susceptible to degradation by hydrolysis of the lactam nitrogen (red circle) and dimerization at the pyrrolidine nitrogen (blue square). Although the prior art taught that ertapenem stabilized from dimerization, the claims at issue in the '150 patent were directed to methods of manufacturing a formulation of the drug stabilized from both dimerization and hydrolysis. Intending to manufacture a generic version of Merck's ertapenem formulation, Invanz®, Hospira informed Merck that it had filed an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) with a paragraph IV certification, and Merck sued for infringement.

At trial, the district court found that the asserted claims of the '150 patent were obvious even though the prior art was silent regarding multiple steps of Merck's claimed process, because the "recipe" was known in the art and the previously untaught steps were merely routine manufacturing steps.2 Agreeing with the district court's analysis, the Federal Circuit explained that the steps were simply "experimental details." Thus, one skilled in the art and having knowledge of the principles in the prior art would have employed the steps to solve the problems of degradation of ertapenem.3

Having found that the district court did not commit legal error in ruling that the previously untaught steps "would have been discovered by routine experimentation while implementing known principles," the court next addressed Merck's objective evidence of nonobviousness.4 The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that Merck's product enjoyed commercial success but determined that the lower court's analysis that such evidence was weakened because of the existence of a blocking patent (a patent directed to ertapenem itself) was flawed.5 The court acknowledged that it previously held that when a patent precludes market entry and has exclusive statutory rights stemming from FDA marketing approvals, objective evidence of commercial success can be discounted.6 But here, the court noted that developers of new compounds often obtain a package of patents protecting the product, including compound, formulation, use, and process patents, and that such patents often result from a restriction requirement or from continuing improvements in a product or process. Accordingly, the court stated that multiple patents do not necessarily detract from evidence of commercial success of a product or process, which speaks to the merits of the invention, not to how many patents are owned by a patentee. Instead, the court clarified that commercial success is a fact-specific inquiry that may be relevant to an inference of nonobviousness, "even given the existence of other relevant patents."7 Nonetheless, the majority did not find clear error in the district court's holding that the evidence of commercial success would not overcome the weight of evidence that the asserted claims were obvious.8

Evidence of copying by others as indicia of nonobviousness was also presented to the district court. Specifically, the evidence indicated that Hospira, after multiple alternative processes failed to yield a stabilized ertapenem, resorted to a process that the lower court found would infringe the '150 patent.9 Here, Hospira argued that evidence of copying is not compelling in the context of ANDA cases because the Hatch-Waxman Act requires generic manufacturers to copy the approved drug. The Federal Circuit agreed with the lower court that the Act does not require the generic manufacturer to copy the New Drug Application (NDA) holder's process of manufacturing the drug. In any event, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the evidence of copying by Hospira of Merck's patented process would not "overcome the weight of the competing evidence of obviousness."10

In her dissenting opinion, Judge Newman admonished the Federal Circuit for its inconsistent approach to analyzing obviousness cases and argued for a return to the standard of evaluating obviousness recited in Graham and reconfirmed in KSR International Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 399 (2007), that "established the factual premises and fixed the placement of burdens."11 She cited several cases in which the court, in her opinion, "recognized and correctly applied the Graham factors" and several cases as evidence of a "shortcut" analysis in which the court "converted three of the four Graham factors into a self-standing 'prima facie' case, whereby the objective considerations must achieve rebuttal weight."12 This analysis, according to Judge Newman, diminishes objective evidence to a rebuttal role and "distorts the placement and the burden of proof," even though the court has previously said that the most probative evidence pertaining to obviousness may often be objective indicia and that they should be "considered as part of all the evidence, not just when the decision maker remains in doubt after reviewing the art."13 Because the district court stated that secondary indicia such as copying and commercial success "simply cannot overcome a strong prima facie case of obviousness," Judge Newman would have remanded the case to the lower court for reconsideration under a proper Graham analysis, i.e., with the proper "analytic criteria under the four Graham factors."14

This case is a reminder that the Federal Circuit's approach to analyzing the Graham factors is not consistent and, according to at least Justice Newman, evidence of secondary considerations of nonobviousness needs to be part of all the evidence, not a rebuttal to the first three factors. The case also sets forth that the existence of a blocking patent or requirements of the Hatch-Waxman Act do not necessarily diminish evidence of commercial success or copying.

Footnotes

1 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v. Hospira, Inc., No. 2017-1115 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 26, 2017).

2 Slip op. at 4.

3 Id. at 9.

4 Id.

5 Id. at 10.

6 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v. Hospira, Inc. at 10 (citing Merck & Co. v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

7 Id. at 10-11. However, it is not clear whether the existence of FDA rights in combination with another patent would have diminished the evidence of commercial success.

8 Id. (emphasis included).

9 Id. at 5.

10 Id. at 11 (emphasis added).

11 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. v. Hospira, Inc., at 2-3 (Newman dissent).

12 Id. at 3.

13 Id. at 4 (citing Stratoflex, Inc. v. Aeroquip Corp., 713 F.2d 1530, 1538-39 (Fed. Cir. 1983).

14 Id. at 6.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.