The constant movement of talent between competitors exposes would-be employers to potential liability for trade secret misappropriation.

If proper precautions are not in place, a key lateral hire may place a company at risk. A newly launched product tainted by a competitor's trade secrets results not only in costly litigation but also in negative press in the industry.

How does a company protect itself from being on the wrong end of trade secret misappropriation litigation? The best tool may be to create an effective "clean room."

Crown Jewels

A company can keep its crown jewels in perpetual confidence and reap the commercial benefits they provide. Properly maintained, trade secrets can offer benefits not otherwise available through patent protection.

While patents are inherently valuable, the public disclosure requirement coupled with their term limits make them, in some cases, less appealing than trade secrets.

Additionally, patent litigation can be expensive and carries a risk that the patents could be invalidated in the enforcement process.

Moreover, infringement can be difficult to prove, especially for patent claims covering methods of manufacturing.

For that reason, chemical manufacturers and ancillary industries often rely on trade secrets to protect their confidential manufacturing processes.

However, these industries may face allegations of trade secret misappropriation and theft, resulting in multimillion-dollar liability claims.1

Trade secrets can also result in criminal liability. The U.S. government has secured several convictions for trade secret misappropriation with penalties that included significant restitution awards. Many of the reported thefts occur at the hands of current or former employees.2

Trade secret misappropriation claims can arise whenever there is an exchange of confidential information between a company and a third party.

The following are typical scenarios that often lead to such claims:

- Joint ventures: Companies engaging in joint ventures with suppliers or other companies to develop products and processes, which require the disclosure of sensitive Though a research and development strategic alliance can be useful for combining the resources and sensitive assets of multiple entities to facilitate technical development, unwitting or unscrupulous participants might usurp the sensitive information provided by other parties for their own commercial gain. Alternatively, a company may inadvertently use another's confidential information exchanged during the joint venture because adequate protection or security measures were not in place.

- Consulting relationships: Companies hiring consultants and contractors, giving them access to otherwise sensitive information, or permitting the contractors' sharing of sensitive business information about the competitors' business practices.

- Acquiring or licensing technology: Companies assessing new technology under a non-disclosure agreement for the purpose of acquiring or licensing the technology and subsequently implementing, disclosing or appropriating those technologies without

- Recruitment: Companies hiring employees from competitors without proper procedures to prevent contamination of their own processes resulting from the use of the competitor's confidential information.3

- Supplier relationships: Companies evaluating new raw materials provided by a supplier and using the supplier's confidential information to develop and seek patent protection of formulations and products incorporating the new raw material.

What is a trade secret?

A trade secret can be any confidential business information that gives a company a competitive edge (i.e., has economic value to the user), if it is not generally known or readily ascertainable by "proper means," such as reverse engineering, and for which the company has established reasonable measures to safeguard its secrecy.

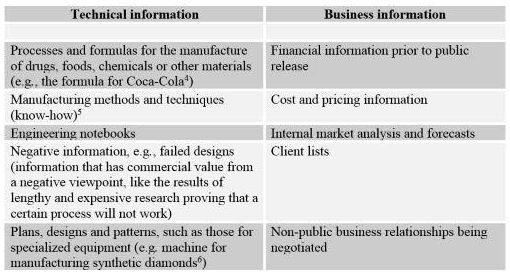

Just as they can do for companies in other industries, trade secrets can cover technical and business information of chemical companies:

Unlike owners of other forms of intellectual property, a trade secret owner does not have to file an application or seek registration identifying or describing its trade secrets.

Instead, protection attaches automatically and perpetually as long as the sensitive information is kept secret by the owner.

Keeping sensitive information secret requires recognizing and identifying the protectable information or processes and establishing proper policies and practices to protect the information.

"The nature and character of the vigilance required of the owner to protect secrecy varies, depending upon a variety of factors," according to IP treatise author Roger M. Milgrim. "Among things to be considered are the size and character of the enterprise (generally, large, sophisticated enterprises are held to a higher 'secrecy effort' standard), the location of the enterprise (elaborate steps that may be required in an 'industrially dense' area may not be required in, say a rural area) and the nature and character of the enterprise's staff."7

Reasonable measures can include advising employees with access to trade secret information of the information's status as a trade secret and educating them on how to protect the information; establishing physical and data security measures to keep secret documents secure; limiting access to the information to a "need to know" group; and requiring people who have access to the information to sign confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements.

What is trade secret misappropriation?

A company commits trade secret misappropriation if it acquires a trade secret through improper means, such as by breaching a contractual obligation or committing fraud or theft.

Misappropriation can also occur if a company uses another's trade secret with knowledge that the person who gave it the

information acquired it through improper means or under circumstances giving rise to a duty to maintain its secrecy or limit its use.

Importantly, independent discovery or reverse engineering of commercially available products or processes does not constitute misappropriation.8

As such, companies accused of misappropriation often claim independent discovery, even when the companies were exposed to the confidential information of their competitors — either through a former employee, joint venture or licensing negotiations.

In those instances, the accused company needs to show that its development process was not contaminated by another's improperly acquired confidential information.

One way to show independent discovery is through the establishment and implementation of "clean room" procedures.

'Clean Room' Procedures

Clean-room procedures attempt to safeguard the development of products and production processes, guarding against any claims that the new work uses another's proprietary/trade secret information.

Companies can also apply these procedures during the development of competing products within a company, such as when a product is being jointly developed with another company while a similar product is also being simultaneously developed internally.

Clean-room procedures have been successfully implemented in the software industry despite the industry's high risk of misappropriation claims.

In software development, liability for trade secret misappropriation does not require proving actual copying of a competitor's software.

Instead, as is true with respect to copyright claims, it is sufficient to show that the accused party had access to the competitor's source code and that the accused party's software is substantially similar.

Exposure to competitive or substantially similar code could create legal risks, especially if a company is developing software with similar functionality.

Under a clean-room scheme for software development, three separate teams of employees collaborate to develop the products and processes:

- Specification team: This group is typically familiar with the competitor's products and processes, and might include individuals who have been exposed to the competitor's confidential information (e.g., the competitor's former employees). The goal of this team is to analyze the competitor's products and create a list of functionality specifications for developing a competing product. The specifications must not include any reference to the competitor's trade secrets or other confidential information.

- Coordination (or "gatekeeper") team: This team serves as the screeners of information provided to the development team. The coordination team evaluates the specifications to keep out protected information that flows in and out of the clean room, and it ensures that all procedures are followed and properly This team often comprises engineers or scientists (to assess the technical information) and individuals trained in trade secret law.9

- Development/design team: This team is often physically and electronically isolated in the clean room. The team is allowed access only to the specifications and information reviewed and approved by the coordination It executes the actual development of the products or processes. The team's members must be screened to ensure that they have no access to alleged trade secrets. As such, former employees of competitors and other employees who might have had access to a competitor's confidential information are excluded from this team.

Similar procedures can be implemented for the research and development in chemical companies.

For example, when a new engineer, having knowledge of a competitor's confidential information, joins a company to work on a competitive formulation or process, that engineer may be assigned to the specification team to analyze the competitor's formulation or processes and to create a list of specifications needed to develop a competing formulation.

However, the employee is walled off from working with or sharing any information related to the competitor's formulation or process with the development team, and any information received from that employee is screened by a coordination team comprised of other engineers and lawyers.

Limitations and Best Practices

Despite their obvious benefits, clean rooms also pose risks that companies must be aware of and take appropriate measures to account for.

Cost of Establishing Clean-room Procedures

Establishing clean-room procedures is expensive. Having multiple teams involved in developing products and processes that otherwise require one team is undoubtedly costly.

Further, maintaining development records and constantly educating employees about the company's procedures will create additional financial obligations.

Deficient Clean Rooms

Suppose, for example, that a research and development team realizes that a competitor's trade secrets were used in the development of the company's top pipeline product.

The team can remove the trade secret information and begin development from scratch with a team that has no knowledge of the trade secret information.

Alternatively, the team can remove the trade secret information and continue to develop the product.

In the latter scenario, it is likely that the final product would still be contaminated by knowledge obtained from the competitor's trade secret information.10

However, as a practical matter, most companies (given cost concerns and business deadlines) would likely not start the development process from scratch with an entirely new team.

Moreover, despite a company's efforts to establish proper clean-room procedures, there is always the risk that contaminated information will still seep through the screens.

A company's good-faith efforts will not absolve it of liability if its processes and products still contain tainted material, or if people on development team are found to have used or maintained competitors' trade secret information.

Best Practices When Establishing Clean-room Procedures

In establishing clean-room policies and procedures, companies should ensure that comprehensive rules are in place to regulate the flow of information between clean- room teams — and make sure that the rules are followed.

The following additional considerations can also help minimize the risk of misappropriation.

First, companies should conduct regular trade secret audits to be aware of their confidential and trade secret information and take reasonable steps, as discussed above, to protect confidential information.

Second, companies should educate new hires, current employees, contract employees, temporary employees, consultants and retirees about the consequences of nondisclosure agreements signed as part of the employment contracts, supplier agreements or a company joint venture as well as the risks associated with contaminating company processes and products using confidential information from competitors.

In particular, companies should ensure that their onboarding processes include agreements preventing new employees from bringing or using any proprietary information from former employers, and new employees should be briefed on the companies' trade secret policies and procedures and safeguards against misappropriation.

Further, when hiring an employee from a competitor, companies should consider placing that employee in a completely different role for a few years.

Third, the clean-room coordination teams should ensure that all work is thoroughly, properly and methodically documented.

The documentation should include as much detail as possible about the personnel involved, the products and processes developed and all sources of information, as well as when and where the products and processes were developed.

This information could come from a variety of sources. These sources include internal development documents (e.g., patent applications, lab notebooks, witnessed invention disclosures, etc.), acquired or licensed-in technologies, and publicly available sources (such as dated articles, books, etc.).

The development records should be maintained in the regular course of business and not only when a company suspects it might be particularly susceptible to misappropriation claims.

Good documentation lays the foundation for substantiating an independent development defense if the company is later accused of trade secret misappropriation.

Finally, companies should make sure to collect and preserve all confidential information from a departing employee before the last day of employment.

Too many companies discover a former employee has left with substantial amounts of confidential information only after that employee has already started working for a competitor.

The risks and costs associated with claims of misappropriation claims are high.

While not guaranteed to protect against all inadvertent receipt of trade secrets, proper clean-room procedures can be a useful tool to guard against claims of trade secret misappropriation for chemical companies to mitigate these risks.

Footnote

1 See, e.g., E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. Kolon Indus. Inc., 564 F. App'x 710 (4th Cir. 2014) (jury verdict for $919.9 million in damages and 20-year worldwide injunction, later vacated for new trial); CardiAQ Valve Techs. Inc. v. Neovasc Inc., 708 F. App'x. 654 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (affirming reasonable royalty award of $70 million, which was enhanced to $91 million, against Neovasc Inc. for misappropriation of three trade secrets).

2 See, e.g., United States Xu, No. 17-cr-63 (D. Del. 2017) (former employee of Chemours Co. and DuPont pleaded guilty to conspiracy to theft of trade secrets related to the development and marketing of sodium cyanide); United States v. Shi, No. 17-cr-110 (D.D.C. 2017) (former employees of Trelleborg indicted for conspiring to steal trade secrets relating to syntactic foam, a buoyant material filled with tiny spheres that has commercial and military uses); United States v. You, No. 19-cr-14 (E.D. Tenn.) (former employee of companies working for Coca-Cola indicted of conspiracy to steal trade secrets related to bisphenol-A-free coatings).

3 The vast majority of cases about trade secret theft involve an employee or business See David S. Ameling, A Statistical Analysis of Trade Secret Litigation in State Courts, Gonz. L. Rev., Vol. 46:1 at 66 (2011).

4 See, g., Thomas v. Soft Sheen Prod. Co., 500 N.Y.S.2d 108 (App. Div. 1986) (formula for hair conditioner); West v. Alberto Culver Co., 486 F.2d 459 (10th Cir. 1973); Coca-Cola Bottling Co. of Shreveport Inc. v. Coca-Cola Co., 107 F.R.D. 288 (D. Del. 1985).

5 Minnesota Mining & Mfg. Co. Pribyl, 259 F.3d 587 (7th Cir. 2001) (know-how like operating procedures, training manuals and process standards for using equipment in making adhesive resin sheeting).

6 Elec. Co. v. Sung, 843 F. Supp. 776 (D. Mass. 1994).

7 Roger Milgrim, 1 MILGRIM ON TRADE SECRETS § 1.04. 8 See, e.g., Bonito Boats Inc. v. Thunder Craft Boats Inc., 489 U.S. 141 (1989).

8 See, e.g., NEC Corp. Intel Corp., No. 84-cv-20799, 1989 WL 67434 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 6, 1989); Bridgetree Inc. v. Red F Mktg. LLC, No. 10-cv- 228, 2013 WL 443698 (W.D.N.C. Feb. 5, 2013) (outlining the clean-room process to be used by enjoined parties wishing to offer or sell the product at issue: designating a physical location within a specific geographic area, limiting employees who may be present in the clean room, requiring a third party "gatekeeper" to review materials going into and work product coming out of the clean room to ensure they are free of trade secrets).

9See, e.g., Patriot Homes Inc. Forest River Hous. Inc., No. 05-cv-471, 2007 WL 2782272 (N.D. Ind. Sept. 20, 2007) (finding a clean room ineffective where months after its creation, "the 'clean room' was still tainted").

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.