Decision: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., 914 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (LOURIE, Bryson, Wallach)

Holding: The Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (“PTAB”) determination in IPR2016-00204 that the challenged claims of U.S. Reissue Patent No. 38,551 (“the RE ’551 patent”), including claim 8, were not unpatentable for obviousness under 35 U.S.C. § 103.

Background: As will be seen, the Federal Circuit’s decision came some 20 years after the original U.S. Patent 5,773,475 (the ’475 patent) issued. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc.’s (“RCT”) RE ’551 patent recites a pharmaceutically active compound used to treat epilepsy and other central nervous system disorders. Claim 8 recites the active ingredient, lacosamide and sometimes called BAMP, in “Vimpat®,” an FDA-approved product for the treatment of epilepsy. In 2012, global market sales of Vimpat® approached $400 million USD, of which some $290 million were in the United States. https://www.marketresearch.com/product/sample-7406645.pdf.

For Vimpat®, the RE ’551 patent is Orange Book listed, covering both the drug substance and the drug product. This article focuses on the amazing story of claim 8, which is directed to the drug substance, lacosamide, rather than on dependent claim 14, which is directed to the drug product Vimpat®. Claim 8, which is still the same as when it first issued in the ’475 patent, reads:

8. The compound according to claim 1 which is (R)-N-Benzyl 2-Acetamido-3-methoxypropionamide.

Solely for sake of completeness, we note that drug product Orange Book-listed claim 14 reads:

14. The therapeutic composition of claim 10, wherein the compound is (R)-N-Benzyl 2-Acetamido-3-methoxypropionamide, which is at least 90% (w/w) R stereoisomer, and wherein the anticonvulsant effective amount is effective to treat epilepsy.

The RE ’551 patent, originally slated to expire March 17, 2017, received a 5- year patent term extension, as reported in https://www.uspto.gov/patent/laws-and-regulations/patent-term-extension/patent-terms-extended-under-35-usc-156 and also reported in the file history of the RE ’551 patent in an August 24, 2012 Patent Term Extension Certificate. Hence, the RE ’551 patent expires on March 17, 2022.

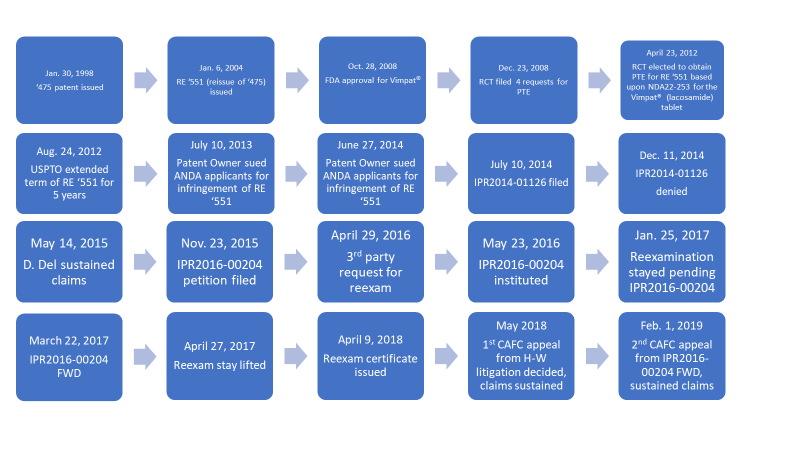

A Timeline of Events for Claim 8 from January 30, 1998 to the Present Day

As noted above, Claim 8, which is still the same as when it first issued in the ’475 patent, reads:

8. The compound according to claim 1, which is (R)-N-Benzyl 2-Acetamido-3-methoxypropionamide.

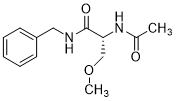

The chemical structure of the (R)-enantiomer recited in claim 8 is:

Dependent claim 8 has had a long and somewhat tortured journey, as seen in the timeline immediately below:

The purpose of this article is to trace the journey of claim 8.

The ’475 Patent Issued in 1998

The claim 8 story begins on January 30, 1998, the day the ’475 patent issued. Claim 8 was independent form, exactly as recited above.

The ’475 Patent Reissued in 2004 as the RE ’551 Patent, and PTE of Five Years Was Obtained

RCT filed a reissue application to perfect a claim to priority, and the reissue ’551 patent issued on July 6, 2004. Dependent claim 8 was unchanged.

On October 28, 2008, the Vimpat® drug product was approved by the FDA, and on December 23, 2008, RCT filed four requests for patent term extension (PTE) based on RE ’551 and U.S. Patent 5,654,301 (“the ’301 patent”) for five years in length as shown in the Table immediately below:

Attorney Docket No. |

Patent No. |

NDA No. |

Approved Product |

|

32555-0002-1 |

RE 38,551 |

NDA22-253 |

VIMPAT®(lacosamide) tablet |

|

32555-0002-2 |

5,654,301 |

NDA22-254 |

VIMPAT®(lacosamide) injection |

|

3255-0002-3 |

RE 38,551 |

NDA22-254 |

VIMPAT®(lacosamide) injection |

|

3255-0002-4 |

5,654,301 |

NDA22-253 |

VIMPAT®(lacosamide) tablet |

On April 23, 2012, RCT responded to the USPTO’s requirement to elect one of the four PTE applications. RCT elected to obtain the PTE for the RE ’551 patent based upon NDA22-253 for the Vimpat® (lacosamide) tablet.

On August 24, 2012, the USPTO responded to that election and extended the term of the RE ’551 patent for five years. As required by the USPTO, RCT corresponded (date unknown) with FDA to amend its Orange Book listing to recite the extended March 17, 2022, date for the expiration of the RE ’551 patent.

|

Patent Data |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Product No. |

Patent No. |

Patent Expiration |

Drug Substance |

Drug Product |

Patent Use Code |

|

001 |

RE38551 |

03/17/2022 |

DS |

DP |

U-1567 U-2140 |

As will be seen, that extra five years of patent term for the RE ’551 patent triggered a veritable explosion in legal efforts by generic manufacturers to knock out the RE ’551 patent. And with some $300 million in annual U.S. sales at stake, the game for RCT was certainly worth the candles spent in successfully punching back over the last two decades

Litigation in Delaware in 2013 and 2014, Decisions in favor of RCT affirmed by Federal Circuit on May 23, 2018

In response to Paragraph IV certifications, RCT brought suits on July 10, 2013 (1:13-cv-01206) and June 27, 2014 (1-14-cv-00834), along with other plaintiffs, in the District Court of Delaware. Claim 8 was at issue in all these suits. The cases were consolidated, RCT prevailed, and the Federal Circuit affirmed RCT’s victory on May 23, 2018. UCB v. Accord Healthcare, 201 F.Supp.3d 491 (D.Del. Aug. 15, 2016), 890 F.3d 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2018), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 574 (U.S. Nov. 19, 2018). Dependent claim 8 survived to fight another day.

IPR 2014-00126 Was Filed Challenging the RE ’551 Patent

After the district court litigations were filed, the RE ’551 patent was challenged in IPR2014-01126, filed on July 10, 2014, by more than ten generic entities, overlapping with parties sued in the Delaware court actions. The generics alleged anticipation of, inter alia, dependent claim 8 in view of each of the ’301 patent and a thesis by LeGall (“LeGall”), as well obviousness over the LeGall thesis and other prior art. Actavis, Inc. v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., IPR2014-01126, Paper 6.

This IPR never got off the ground, as institution was denied. IPR 2014-01126, Paper 21 (P.T.A.B. Jan. 9, 2015). With regard to anticipation, PTAB found that LeGall was not proven to be publicly accessible and hence was not prior art. Thus, the PTAB rejected the anticipation argument over LeGall, as well as the § 103 argument based on LeGall. Id. at 13-14.

No appeal of the denial of institution was filed. The wisdom of the petitioners’ decision not to file an appeal was affirmed on June 20, 2016, by the Supreme Court’s decision in Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee, 136 S.Ct. 2131 (U.S., 2016) (affirming that generally there is no appeal allowed of a PTAB institution decision).

Once again, claim 8 survived attack.

IPR2016-00204 Was Filed Challenging the RE ’551 Patent; Although Instituted, the PTAB ruled against Petitioner in its Final Written Decision (FWD), and the Federal Circuit affirmed

The attacks on the RE ’551 patent nonetheless continued. On November 23, 2015, some months after denial of IPR2014-01126, another generic manufacturer, Argentum, filed an IPR, IPR2016-00204, attacking the RE ’551 patent, including claim 8. Argentum Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., IPR2016-00204, Paper 1. Argentum had not been a party to IPR2014-01126. Argentum also was not a party to the Delaware litigations and the resulting Federal Circuit appeal.

Argentum managed to achieve institution, Argentum Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., IPR2016-00204, Paper 19 (P.T.A.B. May 23, 2016). To be sure, the PTAB continued in its view that LeGall had not been proven to be publicly accessible. Id. at 8-12. The PTAB warmed, however, to certain obviousness attacks made in the Petition. Id. at 12-22. The PTAB instituted the IPR against claims 1-13 of the RE ’551 patent, which, of course included claim 8. Id. at 23-24. This is the only time in the two decades of history of the lacosamide legal disputes that there was a ruling, albeit preliminary, of a reasonable likelihood that claim 8 was unpatentable. But the PTAB hastened to add it was not, at this stage in the proceeding, making a final determination that claim 8 was unpatentable. Id. at 23. And in the FWD, PTAB ruled in favor of the patent owner on all the claims at issue in the RE ’551 patent including dependent claim 8. Argentum Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., IPR2016-00204, Paper 85, at 54 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 22, 2017).

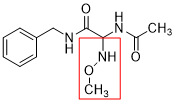

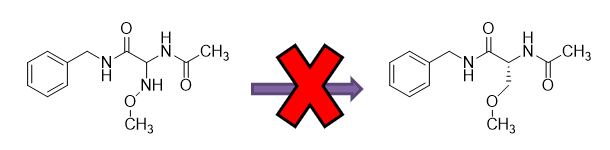

Petitioners employed a lead compound analysis to argue claims 1-13 of the ’551 patent would have been unpatentable as obvious. Petitioners proposed that Compound 3l from the Kohn 1991 article (“Kohn 1991”) was the proper lead compound:

Alleged Lead Compound 3l

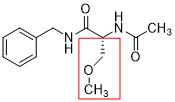

Compare that to the compound of claim 8, with the differences being boxed:

“BAMP” or “lacosamide”

Here, Compound 3l is a racemate and includes an amino (–NH–) linker between the main carbon chain and methoxy group (–OCH3), thus forming a methoxyamino group. In contrast, lacosamide, an enantiomer, features a methylene (–CH2–) linker between the main carbon chain and methoxy group (–OCH3), thus forming a methoxymethyl group.

In finding that Petitioner failed to carry its burden to establish obviousness, the PTAB examined:

1) Whether Compound 3l is a lead compound that one skilled in the art would choose to modify, and

2) If so, whether one skilled in the art would have been motivated to modify the amino linker in Compound 3l to obtain the methylene linker recited in claim 8’s lacosamide.

IPR2016-00204, Paper 85, at 17.

Petitioners asserted that a person of ordinary skill in the art (“POSITA”) would have recognized stability and potency problems with the methoxyamino group in Compound 3l, thus providing motivation for replacing the amino linker with a methylene linker to yield lacosamide. Id. To bridge the differences between racemate Compound 3l and enantiomer lacosamide, Petitioners contended a POSITA would have isolated the (R)-enantiomer from the racemate because Kohn 1991 taught that the (R)-enantiomer possessed greater anticonvulsant effects. Id. at 15.

In its FWD, the PTAB accepted racemate Compound 3l as the lead but nevertheless concluded that Petitioners did not meet their burden in establishing a motivation to modify Compound 3l. Id. at 17. According to the PTAB, the disclosure of Kohn 1991 taught that compounds without a methoxyamino group or nitrogen-containing moiety at the α-carbon had reduced activity and therefore taught away from the proposed modification. Thus, a POSITA seeking pharmacological activity would view conversion of the methoxyamino group as undesirable. Id. at 19, 24-25.

The PTAB also relied on evidence that substituting a methylene linker for the amino linker in Compound 3l would result in a significantly different conformation and altered biological activity. Id. at 22. Finally, the PTAB noted a lack of evidence suggesting modification of the methoxyamino group of the lead compound would reduce toxicity. Id. at 26.

The PTAB also noted evidence of commercial success in that since its introduction in 2009, Vimpat® generated more than $2.4 billion in net U.S. sales and sales of Vimpat® had increased significantly each year. Id. at 39.

Thus, the PTAB, despite finding at the institution stage that there was a reasonable likelihood that Petitioner would prevail with respect to the challenged claims, reversed course in the FWD and held that “[b]ased on the record developed in this proceeding, we conclude that Petitioner has not established by a preponderance of the evidence that claims 1–9 of the RE ’551 patent are unpatentable for obviousness over Kohn 1991 and Silverman, nor has Petitioner established by a preponderance of the evidence that claims 10–13 of the ’551 patent are unpatentable for obviousness over Kohn 1991, Silverman, and U.S. 5,378,729 (“the ’729 patent”). Id. at 4.

The Federal Circuit Appeal from the Decision in IPR2016-00204: Did the Board Err in Holding the ’551 Patent Not Unpatentable as Obvious?

The generics lost the Delaware ANDA litigation and some of those generics subsequently joined the Argentum IPR. After the PTAB upheld the claims of the RE ’551 patent in the IPR, the generics, but not Argentum (the original petitioner), appealed to the Federal Circuit. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., 914 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

On appeal, Appellants maintained that their lead compound analysis rendered lacosamide obvious. Id. at 1374. Specifically, the Appellants argued that a functionalized oxygen was associated with increased potency, and that a POSITA would have isolated the (R)-enantiomer because the prior art references disclosed a racemic lacosamide mixture and improved anticonvulsant activity of the (R) enantiomer of Compound 3l. Id. Furthermore, Appellants urged that a POSITA would have recognized the methoxymethyl group as uncommon and likely to cause problems with synthesis and stability and thus there was motivation to replace it. Id.

To reach the conclusion that a POSITA would have chosen a methylene linker to replace the amino linker of the methoxyimino group in Compound 3l, which both the Court in this appeal and the PTAB in IPR2016-00204 assumed was an appropriate lead compound, Appellant relied on principles of bioisosterism taught by a prior art document, Silverman. Id. In particular:

Bioisosteres are substituents or groups that have chemical or physical similarities, and which produce broadly similar properties. Bioisosterism is an important lead modification approach that has been shown to be useful to attenuate toxicity or to modify the activity of a lead, and may have a significant role in the alteration of pharmacokinetics of a lead.

Argentum Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., IPR2016-00204, Paper 85, at 14 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 22, 2017).

The Patent Owner responded that the record lacked evidence supporting the ability and ease with which the lead compound analysis could be executed, thereby showing a lack of motivation to modify the lead compound. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., 914 F.3d at 1375. The Patent Owner argued that insufficient evidence was presented to show that the methylene linker is the only bioisostere that would result in a compound with more therapeutic and stable properties than Compound 3l. The Patent Owner also argued that relevant literature taught away from removing the amino linker, because such a structural change would result in decreased potency. Id.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board’s determination that Appellants had not established obviousness was supported by substantial evidence:

Even if a person of skill in the art would have been motivated to modify compound 3l, the record evidence suggests that compounds without a methoxyamino or nitrogen-containing group at the α-carbon had reduced activity. …. The evidence also suggests that replacing the methoxyamino in compound 3l would have yielded a different conformation.

Id.

The Court also rejected the Appellants’ bioisosterism argument:

While Silverman does disclose that that bioisosterism may be useful to attenuate toxicity in a lead compound, the record does not indicate why bioisosterism would have been used to modify compound 3l in particular, which already had a high potency and low toxicity, and why methylene was a natural isostere of methoxyamino.

Id. at 1376.

Appellants argued that Kohn 1991 details “stringent steric and electronic requirements that exist for maximal anticonvulsant activity in this class of compounds, including the size of the group on the α-carbon.” Id. at 1374. According to Appellants, their modification retained a small moiety and, inter alia, satisfied this steric requirement. Id. Appellants further asserted that their proposed modification retained a functionalized oxygen atom, two atoms removed from the α-carbon. Appellants also urged that their proposed modification would have been expected to have excellent potency. Id.

However, “Appellants’ predicted potency for ‘racemic lacosamide’ was less impressive than that of compound 3l.” Id. at 1374-75. Appellants had urged that a POSITA would have made the modification to address stability, synthetic simplicity, pharmaceutical familiarity, and acceptability, even if potency were to be lowered in the process. But Patent Owner pointed out that the record lacked evidence that the N–O bond of Compound 3l was sufficiently labile to support Appellants’ proposed modification. Id. at 1375.

In fact, the prior art taught that Compound 3l was stable. The record also lacked evidence that a POSITA would forgo a compound with higher potency and lower neurotoxicity just to obtain stability. Id.

The Patent Owner contended that a POSITA would have considered all of a compound’s properties together. The Patent Owner also pointed out that the generics’ expert’s predicted ED50value of Compound 3l relied on impermissible hindsight, and that the literature consistently showed that substituting the amino linker of α-carbon amino substituents with other functional groups reduced potency. Id.

The Patent Owner further argued that substituting the amino linker with a different functional group would have yielded a significantly different conformation. The art indicated that such a conformational change may affect interaction with receptors and alter biological activity. Id. The PTAB had accepted that conclusion. Id. at 1371.

According to both the PTAB and the Federal Circuit, a POSITA would not have been motivated to modify the methoxyamino group in Compound 3l to the methoxymethyl group in the compound recited in claim 8.

Even if a POSITA were motivated to modify Compound 3l, the evidence did not support a motivation to substitute the amino linker of the methoxyamino group with a methylene linker to form a methoxymethyl group due to reduced functionality. Id. at 1375.

The Intervening Reexamination: Stay Lifted after FWD was Issued and Reexamination Was Concluded after the Appeal of the FWD in IPR2016-00204 was lodged but before the Federal Circuit’s Decision

While IPR2016-00204 was pending, Argentum filed a Request for Reexamination urging that there was a substantial new question of patentability (“SNQ”) for claims 1-13 of the RE ’551 patent raised by the combined teachings of the ‘301 patent, U.S. 5,378,729 (“the ’729 patent”), Kohn 1991, and LeGall.

SNQ Reference |

SNQ Reference is Presented in a “New Light” |

NewTechnological Teaching |

|

’301 patent (Ex. 1019) raises an SNQ for claims 1-13, alone or as evidenced by LeGall (Ex. 1008)

|

Although the ’301 patent was considered during original examination, Patent Owner’s later admissions to both the PTO (Ex. 1020) and District Court (Ex. 1004) confirm that the Examiner misunderstood that Claim 44 of the ’301 Patent does indeed contain an ether (methoxymethyl) at the R3position. LeGall was never considered during examination or reissue. LeGall discloses a compound with an ether (methoxymethyl) at the R3position, as Dr. Kohn admitted under oath to the District Court (Ex. 1038). Moreover, Patent Owner has admitted that LeGall is prior art (Ex. 1004, Joint Statement of Uncontested Facts, ¶86 (e)(e) and ¶87.). |

The compound of Claim 44 of the ’301 Patent contains an ether (methoxymethyl) at the R3position.

|

The USPTO concluded that there was an SNQ for claims 1-13 under the doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (“OTDP”).

During the reexamination, the patent owner canceled claims 1-7 and added new claims 14-27. At the end of the reexamination the USPTO provided a lengthy rationale in affirming claims 8-13 and allowing new claims 14-27. The rationale focused on the lack of motivation to modify prior art compound 3l because modification would result in decreased therapeutic activity and a significantly different conformation and biological activity. The rationale also mentions “no one was interested in [compound 3l] as a lead compound” in 1996, which defeats requestor’s lead compound analysis. Notice of Intent to issue a Reexam Certificate, at 2. The PTO pointed out that, at the time of the invention, there was no evidence that a functionalized amino acid, such as lacosamide, would exhibit any anticonvulsant activity nor do so with minimal side effects.

The PTO thus confirmed claim 8 in reexamination. Thus, once again claim 8 survived. However, it never came up during reexamination that claim 8 depended directly from canceled claims 1-7. The USPTO issued the reexamination certificate.

Hence, at the end of day, following decades of legal dispute, Claim 8 survived untouched. In its journey, claim 8 survived original prosecution, two IPR proceedings, a reissue proceeding, a reexamination proceeding, and two Federal Circuit decisions.

Practice Takeaways

What, therefore, is to be made from this amazing journey of claim 8? At first blush, one might think that the ruling has narrow implications because the obviousness inquiry was very fact-dependent.

This case, however, provides helpful guidance to those in prosecution (whether in original prosecution, reissue, or reexamination) trying to defeat an Examiner’s rejection based on a seemingly minor difference between a claimed compound and a compound of the prior art.

Attacking a Theory based on Bioisosterism

For example, bioisosterism alone is not grounds that would have made the molecule recited in claim 8 obvious. The Federal Circuit held that the PTAB was entitled to cast aside the reference discussing bioisosterism as motivation to modify racemate Compound 3l. Compound 3l already had a high potency and low toxicity. So why would the POSITA go looking to bioisosterism to make a modification? They would not.

The record also failed to indicate why the methylene linker in lacosamide’s methoxymethyl group was a natural isostere of the methoxyamino group of Compound 3l. Notwithstanding the excellent properties touted for Compound 3l, the failure of an Examiner to prove that the prior art modification is a natural isostere of the lead compound is an excellent argument to keep in the prosecutor’s toolbox.

Also, if the rationale for making the chemical modification includes a potency difference, there must be evidence supporting that potency. The prosecutor may also be able to submit a robust and well-supported declaration establishing that a POSITA would predict less potency for the proposed modification, thus eliminating motivation for a POSITA to make a modification. Care, however, should be exercised with declarations, as declarations can be the subject of bitter attacks. See Intellect Wireless, Inc. v. HTC Corp., 732 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

Are the Bonds Proposed to be Modified Labile?

As in RCT, if the bonds proposed to be modified are not labile, why would the POSITA seek modification? That may be yet another reason why the proposed modification should fail and is at least worthy of some consideration if similar facts are involved.

Does the Proposed Modification Involve a Change in Molecular Conformation?

Also, note that in RCT, the change of conformation argument was very effective. The prior art suggested such a conformational change may have significantly affected interaction with receptors and altered biological activity. And the main reference in RCT, Kohl 1991, itself counseled against making a modification that would significantly affect a compound’s conformation. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., 914 F.3d at 1375. Such arguments and evidence may be available to assist your prosecution.

Can the Patent Owner Use a Third-Party Request for Reexamination to Fortify Its Claims?

The reexamination raises additional practice takeaways. The patent owner did not request reexamination. That was done by third party Argentum. And yet, the patent owner was able to take advantage of the reexamination requested by a third party to add claims.

There remains, however, the question of whether claims resulting from reexamination that depend from canceled claims must be redrafted in independent form. To be sure MPEP 2260.01 provides justification to the USPTO for allowing such claims without modification. See MPEP 2260.01 [R-07.2015]:

If an unamended base patent claim (i.e., a claim appearing in the reexamination as it appears in the patent) has been rejected, canceled, or is no longer subject to reexamination due to adjudication in court, any claim undergoing reexamination which is directly or indirectly dependent thereon should be confirmed or allowed if the dependent claim is otherwise allowable. The dependent claim should not be objected to or rejected merely because it depends on a rejected or canceled patent claim or a claim no longer subject to reexamination. No requirement should be made for rewriting the dependent claim in independent form. As the original patent claim numbers are not changed in a reexamination proceeding, the content of the canceled base claim would remain in the printed patent and would be available to be read as a part of the confirmed or allowed dependent claim.

If a new base claim (a base claim other than a base claim appearing in the patent) has been canceled in a reexamination proceeding, a claim which depends thereon should be rejected as indefinite. If a new base claim or an amended patent claim is rejected, a claim dependent thereon should be objected to if it is otherwise patentable and a requirement made for rewriting the dependent claim in independent form.

But just because the USPTO relies on MPEP 2260.01, should the Patent Owner be satisfied? At least one non-precedential case from the Federal Circuit appears to indicate the court’s approval of MPEP 2260.01. See In re Vigilant, Inc. and the City of Port Arthur, Texas 535 Fed. Appx. 928 (2013) (in addressing claim 6, which depended from a claim canceled during reexamination, the court noted that “[w]hile the PTO decision here altered the asserted claims, nothing in the PTO reexamination proceedings rendered Claim 6, or any of the other now asserted claims, invalid.”).

But perhaps a Patent Owner should ask for a certificate of correction to put such a claim in true independent form. Or before the Reexam certificate issues, perhaps the Patent Owner should present an amendment redrafting such a claim in true independent form. Although MPEP 2260.01 may carry the day, the practitioner may wish to tend to this during reexamination and thus extinguish any issues relating to claim dependencies.

Do All the Facts and Circumstances Indicate Any Utility from a Request for Supplemental Examination?

There is yet another worthy consideration to be made: If such IPR and reexamination attacks are raised against one of your client’s patents, would Supplemental Examination (SE) be a helpful option to pursue? If the right facts exist, the answer may be yes.

Of course, there are some barriers to SE. For instance, a SE request is not available if the items of information were already raised as an inequitable conduct allegation in a patent litigation or in a paragraph IV notice letter. 35 U.S.C. §257(c)(2). Moreover, any cleansing effect of a SE occurs only once the SE proceeding and any ex parte re-examination ordered therefrom has drawn to a close. There also is a steep fee for the procedure. But, if there are substantial amounts at stake, the fee is a relative pittance.

At the conclusion of reexamination/reissue/IPR/Federal Circuit appeals, consider filing a Request for SE of the surviving claims and providing all information from original prosecution, reexamination, reissue, any IPRs, and any Federal Circuit decisions. A reason for doing this is that a Request for SE can insulate the claims from a finding of unenforceability based on the information submitted in the Request for Supplemental Examination. For more on this, see Nyshadham et al, “Supplemental Examination Nuts and Bolts: Get it in Your Toolbox and Don’t Leave Home Without It,” AIA blog post June 3, 2019, ; Santos et al, “A Tale of Two Supplemental Examinations: Part 1: Unraveling Confusion,” AIA blog post June 6, 2019, ; and Santos et al, “A Tale of Two Supplemental Examinations, Part II: Surprising Events When Citing Art That, but for a Clerical Error, Would Have Been Cited During Original Prosecution,” AIA blog post June 12, 2019.

And, since a Supplemental Examination request, if granted, results in reexamination, a patent owner might also avail itself of that option to cure dependency issues as mentioned above.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.