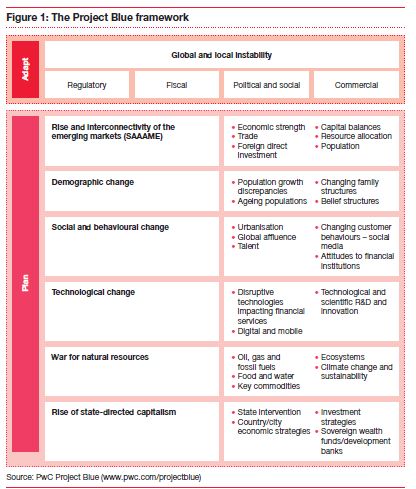

Project Blue is a major research project, designed through interaction with financial services leaders, to provide a framework to help industry, and particularly policy makers, to organise their own assessment of a world in flux, debate the implications, rethink strategies, and, if necessary, re-design organisational structure and business models.

For central banks, this is particularly important and relevant. From greater government intervention and different policy choices, through to the shifts in global investment and growth, Project Blue explores the major trends that are transforming the economies and financial systems, focusing on the impact on the businesses that operate within them worldwide (see Figure 1). Our clients are using the framework to help them assess the implications of these developments for their particular organisations and turn the developments ahead to their advantage.

The world was already changing before the global financial crisis as China, India and Brazil emerged as economic superpowers. The rapidly increasing cross-investment and trade flows between the markets of South America, Africa, Asia and Middle East (together, these relatively fast growing regions make up what PwC terms as 'SAAAME') were also reshaping the global economy. But the crisis has accelerated the speed and broadened the scope of the shake-up. The immediate priority for central banks, especially those in developed markets, is going to be re-establishing a baseline of stability. But the markets that central banks oversee, the currency and monetary positions they manage, and the wider economic drivers that they are there to control, are all going to face significant upheaval as a result of the longer term trends explored in Project Blue.

In this paper we look most closely at the implications of 'global and local instability', the 'rise of state-directed capitalism' (though we do not directly address the growing role and influence of sovereign wealth funds in this context here) and the 'rise and interconnectivity of the emerging markets', as these are likely to havethe most far-reaching impact on central banks.

There is no one way for central banks to deal with these challenges. Strategies and objectives are profoundly affected by the economic circumstances of the central bank's home country (e.g. inflationary pressures, debt to GDP ratio and developed versus fast growth markets) and how integrated it is with the regional and wider global economy. Their response is also going to be shaped by the countries and their central banks' experiences of the financial crisis (level of fiscal, economic and political fallout), their role as regulators (i.e. whether market, prudential or consumer regulation is part of their remit or not), and the extent to which their financial and, to some degree, operational independence, is being challenged by changes in expectations, markets and government policy. All central banks are facing the urgent need to reassess their strategy and place within the wider regulatory and economic management model. And as we describe in this paper, while there is no single infallible model, there are nonetheless a number of considerations that will be pertinent to all.

One common challenge is how to implement and adapt strategies to the reforms being developed by the G20 and its advisers within the Financial Stability Board, in which central bankers are playing a key role. The operations of most of the world's systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) cut across many borders, calling for a high level of international central bank collaboration in monitoring and managing the risks to stability.

For central banks in developed markets, there is the further challenge of how to restore stability when conventional policy options appear increasingly limited. Central banks also need to keep pace with the fundamental changes in many areas, following in the wake of the financial crisis, if they are to sustain relevance, influence and effectiveness. The banks they oversee are being reshaped by cost-cutting, strategic reorientation, fundamental regulatory reform and ever-increasing use of technology in the delivery of services. Central banks in many fast growing emerging markets face the particular challenges of potentially destabilising influxes of foreign capital and the increasingly international reach of their domestic banks. Could these developments create new systemic vulnerabilities?

Organisational change is a natural consequence of strategic re-orientation, though, so far, the organisational shifts have been largely tactical rather than a longer term reshaping. Central banks are seeing fundamental changes in their role and operational scope as they are called upon to work alongside governments and supervisors in moving to a more regulated and interventionist approach to the management of financial stability. With their ability to anticipate and respond quickly and decisively to emerging crises under the spotlight, how can they develop the early warning systems and strengthened operational armoury to respond? How will the demands of heightened politicisation and the need for a more collaborative approach affect their governance, independence and ability to take appropriate action? How can they master the practical challenges created by the bigger and more volatile balance sheets arising from their evolving functions?

Central banks that anticipate, adapt and, where possible, take advantage of the developments ahead, rather than simply reacting to events, are going to come through in the strongest shape and be better placed to influence rather than follow events.

Crisis management: The power of partnership

After helping to deliver two decades of monetary stability and growth, the confidence of Western central bankers has been shaken by their seeming inability to resolve the financial crisis once and for all, even with the huge sums that have been committed. How can they maximise the impact of their interventions and what policy and political challenges might this create?

PwC's Project Blue framework begins with the considerations needed to adapt to the continuing market turmoil within many parts of the world, along with the fiscal pressures, regulatory change and political unrest that is following in its wake.

Central banks are at the forefront of dealing with the challenges. More than four years on from the collapse of Lehman Brothers, many still find themselves manning the parapets as what began as a credit and liquidity crunch has continued to mutate and deepen within many markets, sovereign debt problems, and putting severe pressure on employment and growth. Indeed, for some, the crisis is beginning to take on an air of permanence.

Central banks played a key role in shaping and directing the emergency measures that helped to pull the financial system back from the brink in the crucial early months and have provided a much needed boost to credit, liquidity and market stability since then. But the law of diminishing returns is becoming evermore evident as the level and frequency of financial commitments needed to make an impact, steadily rise. As markets become inured to the medicine, it would appear that each new initiative has to be bigger than the last to achieve the shock and awe effect.

Lately, the most telling market boosts have tended to come when major central banks act in concert, suggesting that collaboration is now the key to decisive intervention. Examples include the coordinated action taken in November 2011 by the Bank of Canada, Swiss National Bank, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank to 'ease the strains in financial markets and thereby mitigate the effects of such strains on the supply of credit'1.

The strength and importance of this collaboration is further reflected in the G20 central bankers' active involvement in shaping the new global standards coming out of the Financial Stability Board (FSB). As all the central banks from the G20 are represented, the FSB is developing norms that apply equally in countries with differing economic characteristics. These standards also cut across markets directly affected by the financial crisis including the US and leading economies of the EU, and those less impacted such as Brazil and Saudi Arabia.

In turn, the FSB is taking the lead in addressing major market developments at a global level, notably the expansion of shadow banking. Mark Carney identified shadow banking as one of his priority areas when he took over as the Chairman of the FSB in November 2011, citing the risk that new capital and liquidity demands would encourage activities to move to the shadow market.2

The multinational scope of most SIFIs and G20 reforms in areas such as recovery and resolution planning being put in place to regulate them, also call for collaboration on the ground. Even where regulatory responsibility is shared with other agencies, their ability to identify concentrations and accumulations of risk and communicate this to their central banks' peers is a vital part of effective macro-prudential management.

But the necessary international policy consensus can be difficult to achieve, with the relatively open-ended commitments favoured by some central banks seen as dangerously inflationary and market-distorting by others. Central banks from smaller economies also face the challenge of how to make their voice heard and exert similar influence to their larger counterparts.

Even when acting in concert, central banks may no longer have the necessary resources to intervene, and therefore need to work in partnership with government and each other.But this raises further potential for policy differences, especially if multiple governments are involved. Proposals such as the European Central Bank's bond buying programme or 'eurobonds' underwritten by all single currency states have met with differing reactions in Europe, not least some political opposition, which underlines what many see as the renewed primacy of politics over central bank policy.

Financial sustainability

Central banks' response to the financial crisis has forced them to innovate and take actions that may have unintended consequences.

The potential inflationary pressure of quantitative easing and other such stimulus measures is seen by some central banks as a risk worth taking to encourage banks to lend more to consumers and small businesses.

But others are now arguing that this period of policy experimentation is more potentially destabilising than the problems that it seeks to address, and may even be sowing the seeds of a future crisis. Jans Weidmann, President of the Bundesbank, has warned of the 'potentially dangerous correlation of paper money creation, state financing and inflation'3.

Particular concerns centre on the artificial inflation of asset prices. In turn, many central bank balance sheets are quite unrecognisable from what they looked like before the financial crisis. The leading central banks, (particularly the European Central Bank, Bank of England and Federal Reserve, who have often acted in consortium during the crisis), as well as some other central banks, have seen increasing financial risk brought onto their balance sheets through asset purchases and other market stimuli. They are now required to manage much larger balance sheets than they have had the experience and expertise to deal with in the past. This is creating additional tensions in their role and financial independence. It might be argued that recent financial risk expansions reflect the reality that the central bank and government are part of a consolidated public sector balance sheet? But what started as a short-term expedient is now proving difficult to shake off and could prove unsustainable in the long run.

The stresses are also being felt beyond developed market central banks as relaxation in monetary policies in the US and the EU lead to an increase in currency values and potentially destabilising capital inflows into many SAAAME markets. Guido Mantega, Brazilian finance minister, has gone so far as to describe developed market monetary policy as 'selfish'4. The impact on central banks includes increased sterilisation costs and foreign-exchange revaluation volatility.

Central banks therefore need a clear balance sheet management strategy that reflects changing market circumstances and public expectations. This includes how much capital they need to hold and the relationship of their balance sheet with that of the government and wider public sector. These policies and their consequences should also be transparent and carefully explained, or they could risk creating further uncertainty and instability.

They should make sure they are forward-looking in their monetary policies. This includes anticipating the impacts of changing trade flow dynamics and considering what effects the supervisory standards will impose on the financial system, liquidity, access to credit and other key macro-economic variables.

With economic recovery still tentative, the timing of stimulus exit strategies will be delicate. But stimulus measures cannot remain in place indefinitely. In particular, there is a danger that markets will become accustomed to stimulus and the cheap money that flows from it, which could increase inflationary pressures and distort the safe operation of the financial system. While economic conditions are likely to vary, this is one of the areas where international co-operation is going to be vital in minimising the potential for further market shocks.

Evolving intervention: New expectations, new models

Before the financial crisis, it was clear that many central banks were able to operate with a relatively high degree of autonomy, especially within monetary policy activities (inflation targeting). However, partnership with government is now a vital element of their ability to make and enact policies. How is this going to change the way they work? How can operational priorities keep pace with developments in the financial system?

The pendulum swing away from the free market towards state-directed capitalism in the wake of the financial crisis is manifesting itself in tighter regulation and increasing government direction of financial services and the wider economy.

For central banks, this new landscape is reflected in their growing role in monitoring and managing financial stability. The problem is that new models are still being developed - the precise responsibilities for financial stability are often vague and may not match the expectations being set by governments, media, markets and the public. A particular concern highlighted by the financial crisis is that problems could fall between the cracks in a multi-agency environment. With a number of different agencies, including the central bank, having financial stability within their remit, there is also the potential for diverse or even conflicting policies. The absence of defined responsibilities is compounded by a lack of clear-cut measures for gauging financial stability and targeting risks, especially when compared to the well-understood inflation and money supply measures used to inform monetary policy.

So where should the lines between government, the central bank and other supervisory agencies be drawn? It is notable that under the Single Supervisory Mechanism proposals,5 it is proposed that ultimate responsibility for specific supervisory tasks related to the financial stability of all Euro area banks will lie with the European Central Bank from 2013. National supervisors will continue to play an important role in banking supervision and implementing the decisions of the European Central Bank. Having championed the separation of central bank operations and banking supervision prior to the financial crisis, the UK is also taking prudential banking supervision back into a subsidiary of the Bank of England. The perceived rationale is that, in view of the criticism of the previous regulatory tri-partite model between Bank, Treasury (Ministry of Finance) and Regulator (FSA), this new approach would improve the speed of decision making and avoid problems falling between the cracks.6

But how to create an operational framework that covers the different dimensions of monetary policy and macro-prudential supervision and formulating aggregate measurement criteria are going to be difficult challenges. This could be even more complicated if the central bank becomes the resolution authority in addition to the lender of last resort.

Moreover, even with clear mandates, there remains the potential for conflict between central bank and government. A case in point would be an attempt by the central bank to rein in on consumer borrowing when the government of the day wants to expand credit availability to stimulate the economy. This mirrors the possible debates between CEOs looking to meet shareholder demands for bigger returns on the one side, and non-executive directors (NEDs) looking to ensure strategy remains within the risk appetite on the other side. If central banks are the NEDs and governments the CEOs, the equivalent of the risk appetite would be clearly defined 'red lights' in areas such as house prices, or levels of household debt, which would help to create agreed points at which corrective action would need to be at least considered. These would be comparable with the inflation targets that guide monetary policy.

The underlying challenge is how to safeguard functional and institutional independence in the face of an extended remit and accelerating political pressure. It is likely that hybrid structures will emerge that combine relatively autonomous monetary policy functions with more collaborative market supervision and financial stability mandates. Central banks also face increased external scrutiny, which will require them to operate in a more transparent and accountable way.

Cultural leap

There are a number of unanswered questions for central bankers as they move into what for many will be uncharted territory. Are they appropriately equipped to take on some of the new responsibilities being assigned to them? How will these developments change the culture and governance of central banks? Ultimately, how can they make a real difference when no matter how banks are supervised, failures have emerged?

Central banks may have lost a lot of their financial clout, but their expertise and moral authority is still going to be important in shaping this more sustainable financial system.

The rise of SAAAME: Managing the risks ofrapid growth

Many SAAAME markets are experiencing rapid and potentially destabilising growth in financial services and the scale and complexity risks their financial systems face, the impact of which is not only being felt nationally, but often regionally and globally as well. How can central banks ensure the stability of a rapidly evolving financial system.

In many ways, the most sweeping of the waves of change outlined in Project Blue is the rise and interconnectivity of the SAAAME markets (South America, Africa, Asia and Middle East). The real issue is not so much the speed of growth within the SAAAME markets, but how interconnected the trade flows between them have become. Trade within SAAAME is growing much faster than the flows between developed-to-developed and developed-to-emerging markets. Banks are following in the footsteps of these rapidly expanding trade routes as they seek to support their customers' moves into new markets.

The shifts in the banking market and wider global economy pose particular challenges for central banks in SAAAME. Many have prided themselves on their cautious approach and hence, ability, to steer clear of, or at least contain, the problems seen in certain developed markets. But as their economies grow, this kind of conservative restraint may no longer be sustainable. Business and consumer needs for more sophisticated products are increasing. A clear case in point is the need to develop the options, futures and hedging instruments needed to encourage more investment in infrastructure and capital market development. Domestic institutions may also want to move onto the global stage, which is extending the required reach and creating unfamiliar challenges for supervision.

How central banks approach this dilemma will depend on where the country sits on its development journey and how quickly economic planners will want the country and its businesses to grow and integrate into the regional and wider global economy. Some countries are content to grow at what they believe is a relatively slow but sustainable pace, or maintain a high degree of economic self-sufficiency. Others will want to tap into the intra-SAAAME curve as quickly as possible. Credit, trade and foreign-exchange strategies will naturally reflect these priorities and evolve in step with wider economic developments.

Frontier vulnerabilities

The financial crisis highlighted the vulnerability of many smaller and less developed markets to destabilising short-term investment flows, many of which were quickly withdrawn as difficulties in investors' domestic businesses took hold.

With much of the 'hot flows' of foreign capital being directed towards banks, the impact on this economically critical sector was especially disruptive. The market values of many emerging market banks multiplied up to ten times in a matter of years. The 'flight to safety' that followed the collapse of liquidity in 2007-08 meant that the credit lines for many frontier market institutions were quickly withdrawn, leaving them high and dry. With capital inflows on the rise again, it will be important to look at how to curb the potentially destabilising impact.

In some countries, further difficulties have been created by the inability of relatively underdeveloped financial services infrastructures, governance systems and supervisory controls to cope with the rapid increase in demand, financial penetration and the sector's size and complexity.

Crucial priorities in creating a more stable financial system include monitoring and managing the risk of asset price bubbles. The quarantining of oil and other commodity income would also help to manage liquidity and promote more stable counter-cyclical fiscal policies. A number of governments have introduced more stringent capital controls to prevent potentially destabilising hot flows.

Within the banking system itself, improving the quality of banking will be critical. While much of the focus has tended to be regulation, strengthening the infrastructure in areas such as IT and payments systems could be equally important in enabling banks to meet growing demand, provide key information for supervisory monitoring and provide more effective support for customers.

Coming through stronger

The game has changed and central banks need to change with it.

Central banks are facing a whirlwind of change in the financial systems and markets they oversee. New policy and governance frameworks are likely to be needed as a result. It will also be important to develop new and closer partnerships with national and international governments. The underlying challenges are cultural as responsibilities and ways of operating undergo fundamental change.

While the specific circumstances and challenges differ, we believe there are six key questions that central banks will need to address as they seek to sustain relevance and effectiveness.

- How is new regulation and strategic re-orientation going to affect the markets you oversee?

- How can you maintain independence from government in controlling credit, monetary supply and other key economic drivers?

- What level of independent resources is necessary to intervene and manage market crises, or is taking action without government funding no longer viable?

- How can you best foster international collaboration and maximise influence over the decisions that affect national and international markets?

- What is the most effective way to anticipate future threats in a fast changing and increasingly interdependent financial sector?

- How will your organisation, governance, communications and deployment of resources need to change to reflect your changing strategy and remit?

Just as the FSB is helping to set the agenda globally, we believe that forward-looking central banks that can address these challenges will be able to exert the necessary influence on government policy and market development to lay the foundations for enduring stability. They are also adapting their culture, organisational and policymaking structures to the new realities they face. At the same time, they have retained the independent and clear-sighted perspectives that have always been the hallmarks of effective central banks.

Footnotes

1 Bank of England media release, 30.11.11

2 Reuters, 08.11.11 and 05.11.12

3 Financial Times, 18.09.12

4 New York Times, 14.10.12

5 European Commission announcement, 12.09.12

6 'A new approach to financial regulation', published by the UK Treasury on 16.06.11

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.