Introduction

PwC1 has worked extensively with family firms across the world for many years, so we appreciate how distinctive these businesses are, compared with today's publiclylisted corporates. Decision-making is very different when it's your own money that's at stake, and as a result family firms tend to have a long-term commitment to jobs and local communities, which gives a significant but often under-rated stability to national economies. In the face of the current uncertain economic environment, governments around the world have been looking for ways to encourage– in broad terms – exactly the same 'patient' and responsible approach to business that the family firm has been practising for centuries.

The results of this year's PwC Family Business Survey prove that there is a great deal the wider corporate sector could learn from the family firm, just as there is far more that governments could do to support them. But it's not all one-way. We believe there's much more the family business sector itself could do to take greater control of its own destiny, not least by working together to press governments for a more constructive tax policy.

This sort of collaboration is already happening in some markets, but family business networks rarely wield as much influence as the conventional trade bodies and business networks. Ironically, the family firm's internal culture and ethos can be an obstacle in this respect, because it can prevent them from seeing the influence they could have if they acted collectively. Indeed, a longer-term community focused approach to business can lead to an unwillingness to take risks for what might be perceived to be a short-term gain, or a failure to seize immediate opportunities quickly enough, and these are areas where the family firm can learn from other corporates.

In this short report, we'll go through the results of this year's survey, and take the temperature of the family business sector across the world. It will come as no surprise that family firms are feeling the strain of the current economic environment, or that government

regulation and bureaucracy are barriers to growth; but there are distinctive challenges for this sector which are the direct result of the unique strengths – and potential weaknesses – of its particular business model.

The results of PwC's 2012 Family Business Survey show that family firms are robust, vigorous and successful – they're ambitious, entrepreneurial, and delivering solid profits, even in the continued uncertain economic environment. These businesses are making a substantial but under-valued contribution to stability and growth, and we believe governments could do more to offer the sort of targeted support that would make a significant difference. We also believe that family firms can do more to help themselves, firstly by adopting some of the professional processes and practices of their publicly listed corporate competitors, but also by being more proactive in finding and securing the assistance they need.

Taking the long view: The unique qualities ofthe family business

This year's PwC Family Business Survey covered almost 2,000 firms across the world, from both developed and emerging markets, representing sectors as diverse as manufacturing, retail, automotive, and construction. The respondents could not have been more varied in their size, location, and industry, and yet there was a marked similarity in their approach to business, and in what they considered to be the distinctive characteristics of businesses like theirs.

We can summarise these characteristics as:

Longer-term thinking and a broader perspective

The family firm is in many ways the epitome of 'patient capital' – these businesses are willing to invest for the long term, and do not suffer from the constraints imposed on their listed competitors by the quarterly reporting cycle and the need for quick returns. 72% of respondents believe that family businesses contribute to economic stability, and this belief is stronger in longer-established businesses of three generations or more, and in mature markets like Europe and North America. 53% consider that businesses in this sector are notable for taking a longer term approach to decision-making.

Quicker and more flexible decision-making

Family businesses often believe that they are more agile and flexible than their multinational competitors, which means they're better able to exploit gaps in the market. Some businesses cited the current downturn as a business opportunity – they've been able to move quickly to acquire businesses or competitors at historically low valuations.

An entrepreneurial mind-set

63% of our respondents thinkthat family businesses are moreentrepreneurial than other sectors ofthe economy, and the larger the familybusiness the stronger that convictionis. Likewise 47% believe that familybusinesses have the ability to reinventthemselves with each new generation.

A greater commitment to jobs and the community

77% of those surveyed believe family firms feel a stronger sense of responsibility to create jobs, and will make more strenuous efforts than other companies to keep their staff, even during tough times. This translates into greater loyalty and commitment from those they employ. 70% agree that community initiatives are important to the family firm.

A more personal approach to business based on trust

78% of respondents consider that the family firm is notable for the strength of culture and values, and this belief grows stronger with time, rising to 85% for third generation firms. Many believe that they win business because they are closer to their customers, and have a more personal relationship with them – indeed that they are chosen precisely because they are not multinationals.

Family firms consider these distinctive qualities to be a source of real competitive advantage and integral to their business model. This sentiment is just as strong among those who have been brought in from outside to manage the firms as it is among family members, as the Wates case study overleaf illustrates. But it is also clear that other aspects of this business model can be a hindrance to growth, whether by generating internal conflict or rendering the business too risk-averse. We will look at some of these issues in more detail in due course, after a brief resumé of the current state of sentiment in the family business sector.

"In a family owned business you tend to think on a long term basis, not a short term basis. You tend to think about your business over generations and not just only based on profits" (Austria)

"Each family business is different, but the ambition and dedication of the family to grow the business is always there" (India)

"When you are a privately held company you have the ability to change the direction rapidly and do not have a board of directors that dictates what you have to do" (USA)

"Family businesses will have the chance to fill niches that the corporate companies cannot cover because they are not as flexible as self-owned companies who can realise new ideas" (Switzerland)

"We have a more autonomous decision-making capacity. And especially more flexible management" (France)

Building on strong foundations: Wates

Name: Paul Drechsler, Chairman and CEO, Wates

Paul Drechsler is the first Executive Chairman from outside the family to run the Wates business after four generations in family control. The Wates family is still passionately involved in the day-to-day running of the business, with a fifth generation keen to become involved.

Sector: Construction

Market: UK

Founded: 1897

Turnover: £1bn

What are the main differences that you've seen of working in a family business versus working within a public company?

First is that in a family business the shareholders are unambiguous about the fact that they want to be invested in the enterprise. Secondly, they want to be invested for the long term, and the great family businesses see themselves as being good stewards of the enterprise for the next generation. So they take a very long term perspective, and find the right balance between long-term and short-term performance. In addition to all of that, they can offer customers a commitment and a continuity that public companies can't offer because they are at the beck and call of their shareholders, who can change their minds on ownership tomorrow morning. Our true USP is the fact we are totally committed to the industry where we operate, and to our relationships with customers and communities and the people who work for us.

Could you talk about the company's values – their attitudes to the local community, and to employees?

In Wates above all it's about people. It's about creating a culture and work environment where people will be highly engaged, and highly motivated to deliver our promise for customers. More than that, wherever we build and operate we want to leave a positive contribution and a positive legacy to the local community, so we're always involved in community projects, sometimes one-off, but very often we're involved in creating employment opportunities for the long-term unemployed. We've had nearly 600 candidates through our Building Futures programme over the past five years. The Wates family have had a long tradition of charitable giving and a few years ago they set up a family trust to give to causes that resonate with the company's strategy and priorities, such as helping the long-term unemployed or disadvantaged children.

And how many family members are involved in the business now?

There are five active shareholders, and three of the previous generation who are less active, but are still deeply interested, because I think that in a family business your interest grows the older you get. There are a lot of other family members – brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces – but the family have focused on maintaining a narrow shareholding base through the course of their history, and each generation has reduced the number of shareholders to keep it highly concentrated, which is a source of strength.

What are the challenges of being a non-family CEO?

For a family business to appoint a non-family chief executive is an extraordinarily big decision. It shouldn't be taken lightly, and while it will work for some families, it won't for others. I would strongly advocate that family businesses have external nonexecutive or advisory directors, but that's still a huge decision for a family business to take. Each family has to find the leadership and governance model that will work for them in their context, for their stage in development, and for their stage of evolution as a family. I think it's a great privilege for a non-family member to lead a family business, but it's also a huge responsibility, which can be just as demanding as leading a public company.

Name: James Wates, Deputy Chairman, Wates

James Wates has been deputy chairman of the family firm for six years, and has never worked anywhere else. His son Piers will be the fifth generation to become involved in its growth and expansion, but he plans to gain experience outside the business, as well as a broad range of skills within it, to prepare him for the challenge of leadership in the future

How has the business changed since you brought in an external CEO?

When we made the decision to appoint a non-family chief executive it was a brave move, but absolutely the right one, because the dynamic definitely changed. Previously people were empowered to make decisions, but they would often look to the family to take the lead. Whereas now, people get on and make their own decisions, and take ownership of the consequences. It's definitely a crisper, more agile business today than it was then.

How did the decision come to be made?

The previous generation of owners was structured as five equal partners, and while there was no constitution per se, they had evolved a way of working during their term of stewardship. But when we came to transition from one generation to the next, it was clear that there would no longer be five equal partners, so we needed some guidelines and parameters within which we would work. That's still evolving and being fine-tuned, now that we have non-family executives running things on a day-to-day basis. I think it hasn't been really stress-tested yet, mainly because the business has been going very well. The challenge will come when things don't go quite so well, but I am confident that the structure we've got in place now will help us to manage that.

"Family-run businesses tend to have more loyalty toward their staff – people are not just a number" (Malta)

"The things that are really powerful about family businesses are the values, which are genuine corporate responsibility" (UK)

"A lot of our customers like doing business with us because we have good values. We can adapt more readily to customers' needs because we are flexible" (USA)

"Our commitment is that we're going to be here for 20-30 years plus. So we will be there for our customers. I can't say that about many of our competitors" (UK)

The family firm in 2012

So what has our survey told us?

Here are some of our key findings:

Family businesses are thriving globally

65% of family businesses have grown sales in the past year, compared with less than half in 2010, and there was particularly strong growth in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Middle East. Only 19% of our respondents saw a reduction in their sales in the last year, as against 34% in 2010.

Family businesses are ambitious and confident about their prospects

Over 80% of the businesses we spoke to anticipate steady or aggressive growth in the next five years, and 39% of those who aim to grow are very confident about their company's prospects over that period. This increases substantially for companies in India, the Middle East, Singapore, South Africa, and South Korea. Given the low levels of confidence in other sectors of the economy, we believe this is powerful proof of the significant role family businesses can play in creating jobs and stimulating recovery.

The economic environment remains the key external challenge

Just like every other business, the family firm is facing major challenges in the current downturn, and in this respect there is little change from the last survey we ran in 2010. The three issues identified by most respondents were market conditions (54%), competition (27%), and government policy and regulation (27%). The latter category, however, showed a very wide variation on a market-by-market basis, ranging from 64% in Greece and 46% in the Middle East, to as low as 6% for Austria and 3% for Sweden.

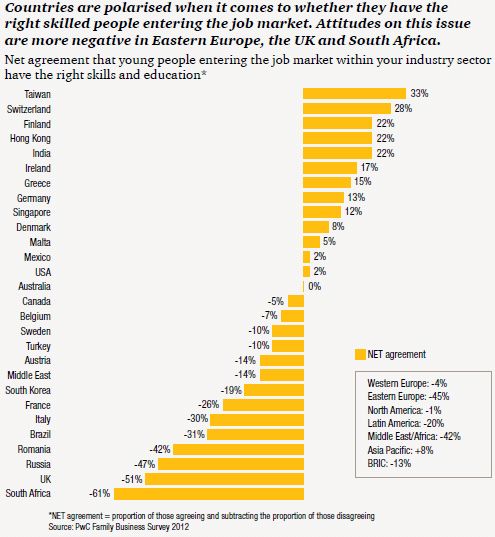

Internally, the main issue is the recruitment and retention of skilled staff

The recruitment of skilled staff and shortages of labour have become more acute challenges than they were in 2010, increasing from 38% to 43%. By contrast, the need for company reorganisations or restructuring is no longer so pressing, though larger companies with a turnover of more than $100m were more likely to cite this as an issue. Cashflow and cost control has also reduced significantly as an issue from 30% in 2010 to 17% in 2012, which suggests to us that many businesses have now taken the action needed to streamline internal processes, improve inventory control, and reduce debtors. A number of businesses also cited the importance of establishing or improving their internal and IT systems, especially in relation to regulatory compliance.

"We need to make sure the business model can cope with change in the market" (Australia)

Looking ahead: Emerging issues for 2017

Even though most family firms are confident about the prospects for their business, there is still some uncertainty about what the future holds.

The economy remains a cause for concern

59% of our respondents cited price pressures as a likely future issue, and this was particularly prevalent in the construction and automotive industries. 40% pointed to increased competition within the market, often driven by the entry of new players, and 66% cited the general economic situation – those companies anticipating a business contraction tended to cite this as the cause. 39% believed regulation would continue to be an issue, and 27% anticipated growing challenges relating to their supply chains.

That the economic crisis we are experiencing will restrict liquidity in all enterprises, including family ones." (Mexico)

"If globalisation and mergers keep taking place in every business, then that is a big challenge for family businesses" (Malta)

"We need more international thinking – it's a challenge not to limit the company to the local market" (Belgium)

"International competition is now much more structured, much more professional, but on the other hand, this leaves large market niches that large companies are not attacking, precisely because of the agility of family businesses" (Mexico)

"It is the era of the multinational" (Romania)

"Our short product life cycle means that we need to constantly produce new ideas and new products to stay in the market" (South Korea)

"Potential employees think that within a family business they will not have a future. In order to attract and retain talent we must create an enabling environment for the future" (Singapore)

"Some families may be ready to withstand the storms of the economic crisis but more likely to collapse at the first dispute among family members" (Middle East)

Globalisation will be crucial to success – or failure

The issue that emerges more strongly for 2017 and beyond is that of globalisation. There is clear apprehension about the impact of an ever more international approach to business, and the growing power of global megabrands, though many businesses remain confident that local knowledge, agility, and the ability to exploit profitable niches will keep the family business buoyant:

Innovation will be vital to secure competitive advantage

Turning to the internal management of the business, the key emerging issues were innovation, skills, and succession planning. 62% of respondents cited the need to continue to innovate, and 37% anticipated the need to invest in new technology. Companies in Italy, Turkey, and South Korea were particularly concerned about innovation, and firms planning to grow aggressively were also more likely to focus on this.

The war for talent is still waging – certainly for family businesses

Attracting appropriately skilled staff (58%) and then retaining them (46%) were also high-profile concerns for the future, and again, especially for those planning high levels of growth. Many respondents said that it is particularly difficult for family businesses to attract talented employees with the right qualifications, because the brightest candidates tend to prefer working for listed multinationals, where the career path is clearer, and there is the possibility of equity at some stage.

The transition between generations can build the family firm – or break it

32% of our respondents were already apprehensive about the transfer of the business to the next generation, and 9% saw the possibility of family conflict as a result. Some family businesses are planning to manage the transition process – and reinforce the business for the future – by bringing in external management. Taken overall, 64% of family businesses have non-family members on the board, a figure which increases to 75% for firms with turnover of more than $100m. However, this overall figure masks considerable differences across the world – for example, the numbers with non-family directors are very high in Denmark (92%) and India (96%), and also high in Asia Pacific as a whole (74%), partly because a very high proportion of family businesses in this region are listed, and are therefore required to have independent Board members. By contrast, the numbers are as low as 49% for the UK and North America.

Equipped to succeed: LL Bean

Name: Chris McCormick, CEO

Chris McCormick is the first non-family member to run the LL Bean business. The company sells its distinctive outdoor apparel and equipment to 160 countries across the world, and has retail outlets in the US, Japan, and China.

Sector: Clothing

Market: US

Founded: 1912

Turnover: $1.6 billion

Has being a family business helped you through this economic climate or affected it differently from public companies?

It has definitely helped – we don't play to the Street, or to the quarterly results cycle. In fact, in 2010 we went to the Board and recommended that L.L.Bean have an 'investment year' and allow profits to fall – we needed to make a big investment in marketing and attracting younger customers, and they agreed. Family members understand we want to be around for another 100 years and investments in growth are critical to the long-term financial health of the business. As a private company, we can maintain the balance between retained earnings – for an adequate level of investment in the business – and the earnings requirements of our family shareholders. That collaborative approach with shareholders to business strategy is tough to accomplish in a public company.

How does succession work at LL Bean?

Leon Gorman chairs our family Board of Directors following his 40-year leadership of the company as President and CEO. He oversaw the seamless transition of the President and CEO role over 10 years ago. Similarly, Leon is preparing for an eventual transition of family leadership. He has established a 3-member family Governance Committee made up of fourth-generation family members. The mentoring and development process is underway as family members remain active in board and committee matters, and now the fifth-generation of family are becoming involved with orientation sessions around the business and learning opportunities about their future responsibilities. At the executive level, we have a very structured leader development process with each of our current senior leaders being reviewed and evaluated on their contributions to preparing leaders to assume these senior roles. This process has been moved down through the organization with leaders at all levels expected to contribute to succession planning.

Do you believe your family-run business gives you an advantage over your competition?

I think we do have an edge. We stick to our core beliefs – customer service, quality, outdoor recreation and our family ownership. We work as a team with shared values. The people part of our business is very important to us – whether employees, customers or communities – and the ownership structure encourages this focus. Additionally, these shared values have allowed the business to maintain a consistent point of view, a consistent experience, a consistent message. This is what differentiates our brand in the marketplace and keeps us relevant. We believe that to sustain our success over time, we have to add value to the interests of all our stakeholders – employees, the outdoor recreation community, our local communities, vendors and of course, our customers. If we do these basics well, profitability will follow, as it has now for over 100 years.

Scale, skills, and succession:

Special challenges for the family firm

As the survey results make clear, family firms are a vigorous group of extremely ambitious entrepreneurs, many of whom are running highgrowth successful companies. However there are particular hurdles to overcome, if the family business sector is to fulfil its full potential, and achieve its ambitious growth plans. Some of these are specific to their particular business model – such as succession planning – but others are more general commercial challenges, which give rise to particular difficulties for a family business. As the LL Bean case study illustrates, these present themselves in the form of 'tipping points': moments in a firm's evolution where key decisions have to be made, and the future direction of the business is determined.

Long-term growth and profitability depend on the successful negotiation of these tipping points, which is why we've issued a quick-reference guide for family businesses in parallel with this report, entitled Scale, skills, and succession: Tackling the tipping points for family firms.

Tipping point 1: Scale

The first of the tipping points is scale: the moment when a business achieves a certain size but can only progressfurther by making a significant stepchange. This may take the form ofa new opportunity in its domesticmarket, prompted by the actions ofa competitor or the introduction ofa new product or innovation, but byfar the most common tipping pointrelating to scale arises when the businessbegins to export for the first time.

"We have an amazing culture in the business. And I think part of the reason why that culture is so good

is because of that family feel. So it's the trick now of keeping that feel and that culture but also evolving beyond the family business, because to me as a family business it was quite reactive and I think now we need to be a little bit more strategic" (Australia)

"[The greatest challenge is] consolidation through globalisation. Customers are getting bigger, which will put greater pressure on size of the family businesses as against large multinational or publicly owned corporates. In other words, scale" (Australia)

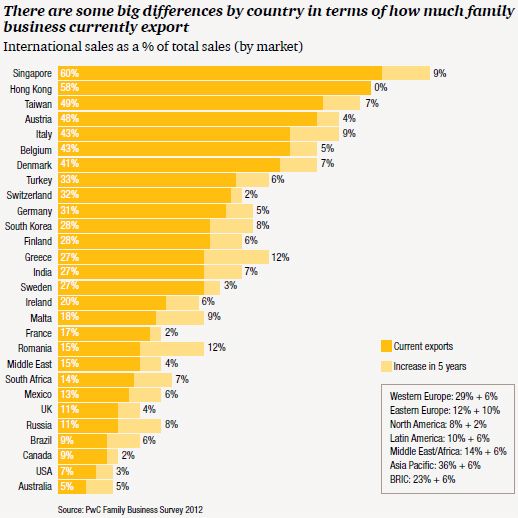

The challenge of Internationalisation

While a quarter of our respondents plan to remain steadfastly domestic, anticipating no exports now or in the future, a significant number of the businesses in our survey are looking to achieve their growth plans by starting to export overseas: the current average proportion of foreign sales is 25%, but respondents predicted this to rise to 30% within five years, and this rises to 35% for those hoping for radical growth. The variation by market is, however, extremely wide, ranging from 60% for a small externally focused market like Singapore, to 7% for the USA and 5% for Australia.

Cutting the figures another way, 67% of respondents had some level of international sales in 2012, but 74% expect to be in this position by 2017. The countries most likely to see an increase in exports are Romania (77%), Greece (70%), Turkey (64%), and Italy (67%).

When they were questioned about the challenges of becoming an international business, our respondents cited understanding the business culture overseas (20%), competition (19%), local regulations (19%), exchange rate fluctuations (16%), and local economic conditions (16%) as the main ones. A number also referred to the difficulties of managing a far more complex international supply chain.

Finding the finance

Almost every business faces a version of this particular tipping point at some stage in their growth, but for family businesses the decision is often more complex. These businesses can feel disproportionately nervous about taking such a step, and a firm run only by family members will generally lack any experience of doing so. They may also be reluctant to contemplate a significant re-structuring of their operations, partly because they could fear this could lead to a dilution of their distinctive culture and values.

Even more crucially, family businesses often face difficulties accessing significant levels of new capital to fund expansion.

Most family businesses have an instinctive aversion to leveraging their balance sheet, and manage their borrowings very tightly.

Under these circumstances raising substantial growth capital will always be a problem, and the firm's options necessarily limited. A more conventional start-up will aim to grow fast in anticipation of a quick sale, and will finance that growth from high levels of debt or by offering substantial equity stakes to venture capital investors or business partners. In theory, a family business could do the same, but family businesses will usually be growing more slowly, with low debt, and very few of them are prepared to offer the equity stake external partners would require.

This problem becomes even more complex with each succeeding generation since many long-established family firms have large numbers of family shareholders, many of whom will be reliant on their dividends and very risk-averse, which means there are unlikely to be many family members who are willing or able to invest new funds of their own. At the same time, the mainstream capital markets are not open to family businesses that are wholly privately-owned, which means that often the only practical option is bank debt, though in the current market this is both restricted and expensive. Mortgaging either physical assets or the receivables book can help reduce the costs, but many family firms see this as 'selling the silver', and are wary of the message it sends to their customers.

The difficulty in accessing finance may be one reason why there is a marked tendency for family firms to focus their export efforts only on neighbouring countries, or those with historical ties to their home market, such as India with the UK. Likewise, family firms can struggle not only to fund but to staff their overseas operations, since family members may be reluctant to relocate, but equally reluctant to hire someone sufficiently senior and experienced to do the job for them. This can become a stumbling block to long-term growth.

"Operating in many places is hard work. We operate in 50 countries and they all differ from each other. We have to learn local cultures and habits and financial legislation and taxation vary from country to country" (Finland)

"Family businesses tend to finance their growth from their profits, so you need to be more careful. Family businesses have to compete with global companies or public companies where resources tend to be much bigger" (Middle East)

"Limitations in their skills base [is an issue]. They may be lacking some skills amongst the family members. This could be particularly evident in the next 5 years when Dad moves on" (Ireland)

Exporting is clearly an area where family businesses can learn from other multinationals, but they don't always have to bring in staff from those companies to achieve this. Partnerships and alliances are a powerful way of gaining insights from academic institutions or larger corporates, and this can range from formal business agreements or agency arrangements in new overseas markets to informal networking, to the sort of creative collaboration which is facilitated in the UK by the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA). Through programmes like Corporate Connections and the P&G Corporate Open Innovation Challenge, NESTA provides opportunities for small firms and entrepreneurs to work with – and learn from – large multinationals such as Procter & Gamble, BASF, GlaxoSmithKline and Virgin Atlantic.

Tipping point 2: Skills

Some family businesses may be wary of exporting because they lack the specific skills and experience they need to do this effectively, but their reluctance may also spring from an understandable caution, or an inadequate understanding of the real nature of the risks that international expansion would entail. It's clear from our survey that the identification, assessment, and management of risk – in its broadest sense – is one of the wider skills that many family firms need to develop. Others cited by our respondents range from specific areas like innovation, Intellectual Property, and IT, to the need for a more focused and strategic approach in managing the business. Anticipating and addressing regulatory requirements and changes are a particular concern.

Mind the gap

This lack of skills can lead to a lack of confidence, and hence to a more general unwillingness to try new approaches, or experiment with new ideas.

According to our survey, the majority of family businesses recognise that skills shortages can be a problem, and address it by bringing in external managers to either supplement or replace family members in key positions.

Hiring professional managers can solve many of the commercial issues a family business may face, and supplement any lack of home-grown skills, but it can raise challenges of its own, which may not always be immediately obvious.

Our experience shows that there are many senior people in family firms whose actual role and responsibilities bear little relation to the title they hold: we've come across COOs who are in reality chairmen, and many CEOs who hold that title by virtue of age and seniority. Some family businesses solve the interpersonal issues that can arise at succession by allocating specific job titles by way of 'compensation', but this can make it extremely difficult to discern where the real skills gap lies, which leads to a lack of clarity both within the management team, and for the business as a whole. Without a comprehensive and objective assessment of skills the decision to hire in from the outside can mean that the wrong person is recruited, which will make it all but impossible for that executive to do the job they were hired to do.

Likewise it is a very different matter to own a business than run it, and some first-generation entrepreneurs can find it particularly difficult to 'let go'.

Re-engineering the family name: Wikov

Name: Martin Wichterle, Owner

Martin Wichterle began his career by studying geology, and founded his own business with a partner in 1990. The Wikov family firm had started life as an agricultural machinery-maker in the 19th century and enjoyed international success before being nationalised in 1946, and later being acquired by another [conglomerate] which subsequently went into liquidation. It was a stroke of luck that Martin was then able to buy the trademark, and reorganise his own growing group of engineering companies under the old family name.

Sector: Engineering

Market: Czech Republic

Founded: 1880, then re-established in 2004

Turnover: CZK 1,6 bn (EUR 64 milion)

Have you considered recruiting a professional management team to run the Wikov group?

I do not run the company day-to-day. The company has a CEO and I no longer wield the powers of an Executive Director. I have not completely withdrawn from an active role, but 90% of the business happens without me. I get involved of course when we are negotiating important deals and the customer wants to talk to me, and in key investments and finance, but the running of the company is in the hands of the professional management team.

Do you feel that a family firm has an advantage compared with the multinationals, especially in terms of decision-making and taking a longer-term view?

I would definitely agree with that. When you deal with any family firm, it is relatively easy to reach a deal – the decision-making is quicker and more flexible, and those firms are also far more likely to lay their cards on the table. That's one advantage. Of course, it is relatively easy for an owner to be flexible about changing strategy, which means the firm can respond immediately to a situation arising on the market. Logic dictates that any big multinational will need longer to approve a change like that, and need a certain amount of courage to do so. The second thing you mentioned is the long-term view and that is definitely true as well. An owner who knows what he is about works less on the basis of market research and surveys, and more from intuition, according to what he sees in the business.

Does being a family firm with close ties to a particular local area give you an extra sense of responsibility towards that community and your employees?

I do feel a sense of responsibility towards two things: I don't just feel it towards the employees who work here, which is logical, but I also feel a sense of responsibility about how the company works with the local community. There is a difference if you have a company in a big town, or somewhere where there are 500 people and the local community depends on your factory. When I started work at firms which had previously been state owned, I was absolutely flabbergasted by how de-motivated the people were. All they were doing was going to work and they weren't able to feel any pride in what they were doing. An important part of our success for me is that we've managed to do something that the people who work for us are proud of – they get a sense of pride from their contacts with major customers all over the world, on every continent. They share in our success.

The same applies, of course, if the business is handed down to a successor, but the potential for conflict can be more pronounced with an experienced manager with strong ideas that may well differ from the owner's. Family businesses that bring in senior executives to run their firms need to learn how to 'manage their managers' to get the most out of them, and a key part of this involves understanding when interference will be a hindrance, and when it can be beneficial, or even vital. This might include, for example, bringing their influence to bear to ensure that the culture and values of the firm are protected.

Conversely, managers of family firms need to understand and appreciate the very different environment they are going into, and adapt their working style accordingly. For example, anecdotal evidence suggests that employees continue to consider that they work for a 'family firm' long after the members of that family have ceased to be actively involved. This can be a source of competitive advantage in terms of loyalty and commitment, but it can also create tensions and unrealistic expectations, which need careful management.

"[The risk is you have] a narrow vision in terms of experience, and need to inject new blood to get a different perspective. You can get complacent with a stable mind-set and it would be better to be open or receptive to change" (UK)

"[We need to] bring outsiders onto the board of the company, and learn how to deal with that. Also the organization of internal processes to streamline our operations. In other words, the professionalization of management" (Brazil)

"A family business can be hampered by an insistence on continuing with a lowperforming line of business. Emotions can dominate, and founders can become obsessive about control" (Turkey)

"In the event that someone is not pulling their weight, it is much more difficult to make a business decision that you should make – there can be a conflict between the head and the heart" (Ireland)

"Family businesses do not place enough importance on proper procedures and governance" (Middle East)

Hiring independent non-executive directors can be one way to inject valuable experience and expertise, but it is often hard to find the right people, and if a family business takes this route it's vital that the NEDs are given the scope they need to be both constructive and objective, and that the family is prepared to take that input on board.

Tipping point 3: Succession

The very essence of the family business is, of course, that it has been passed from one generation to the next, but the moment of transition – and the years leading up to it – can make or break the firm's future success.

Own, manage, or sell?

41% of our respondents intend to pass on both the ownership and management of their business to the next generation, though it was noticeable that more than half of them still remained unsure whether the next generation would have the skills and enthusiasm to do this successfully.

25% intend to pass on their shares but bring in professional managers, citing the next generation's lack of skills as the main reason for this decision. The numbers were – understandably – slightly higher for those looking to start exporting for the first time.

The majority of the remaining 34% of our respondents had either not yet decided what to do with their business when they retire (12%), or were planning to sell or float it (17%). Those in the latter category had come to this conclusion either because the next generation did not want to take the business on, were too young, or did not have the necessary skills. Flotation will probably not be an option for most family businesses, which leaves acquisition by a larger public company or a private equity firm as a far more likely outcome. Family businesses that are considering taking this route have to consider carefully what this would mean in practice, and what they might need to do to configure or restructure their operations to make them an attractive prospect for a commercial buyer or private equity investor. Those who value the personal nature of their business and the strength of its values need to accept that both of these are likely to be diluted – if not eliminated– if the firm is acquired by a third party.

Regardless of the form it takes, the moment of transition is rarely completely straightforward, and is one of the most common sources of conflict within both the family and the business

On the crest of a wave: Seafolly

Name: Anthony Halas, CEO, Seafolly

Anthony Halas runs the highly successful swimwear brand that was set up by his father over 30 years ago.

Sector: Swimwear

Market: Australia

Founded: 1975

Turnover: A$95m, with exports to the UK, the US, Canada, Germany and elsewhere in Europe.

How did the Seafolly business change when it passed from your father to you?

My father was an incredible trader – he knew how to pick good product and buy it at a good price and he was an amazing salesperson. But obviously now the business is this size, you can't get as involved in the day-to-day, it becomes a question of about managing teams and employing the best people to do the job and being more strategic. So a very different management style is needed now, compared to when he was running the company.

Where does the business go next?

I want to double the business in the next three to five years. I think the international opportunities are huge for us. We're looking at my first retail site in the US, and if that's successful we'll quite quickly roll out a few stores over there. We just opened up our first international store in

Singapore which has been very successful, so we're looking for a second site there. We're also expanding the Seafolly brand beyond swimwear – about 25% of our business is now coming from non swimwear categories

What's your biggest challenge now?

Currency fluctuations are a big risk at current levels – at the moment we're trying to maintain prices but that means we're taking a hit in margins. A big part of our business is the stock, and holding stock of swimwear is a risky business, because it's so weather-dependent. So as the business grows, your stockholding is growing and your risk is growing. So that's something that we really have to control. The whole international manufacturing issues is a challenge to – at the moment we manufacture in China, but that's a market that's changing fast – it's not easy to predict what will happen to wages and labour availability there,. So we have to remain flexible and keep other options open.

What's the advantage of being a family firm?

Definitely the ability to be able to make good decisions and react quickly – not being bound by outside investors who are purely looking at the bottom line. I think what a family business can do is really invest in the future. In the early days we would forgoing profit for investing in the brand and up till about six or seven years ago up the money was going into investing in marketing, I don't know if you could have done that if you were a public company or had private investors. It's all about long-term vision.

"It would be the succession to the next generation that a family company will face, and the ability to survive the succession. It is often here it goes wrong" (Denmark)

"Family politics [is an issue], specifically people being hampered by family members. In our culture, for example, the grandsons do not tell the grandfathers what to do, but that's not necessarily the case in a normal business" (South Africa)

"Corporate governance standards are an issue – if we want to grow then our standards will need to be up to speed with international best practice – in India the majority are not up to speed" (India)

"Mentoring and developing the next generation family members is crucial to the success of the family business" (Middle East)

Coping with conflict

Conflict can arise from any number of different causes, from professional to personal. These might range from disagreements about future strategy and direction, to the personal performance and remuneration of individual family members. The consequences can be temporary and minimal, or so disruptive as to overwhelm what might otherwise have been a perfectly healthy business. In the Middle East, for example, some family disputes have ended up in the courts, and the assets of the entire firm have been frozen until the case could be resolved.

A good number of our respondents had put measures in place designed to deal with potential conflict, ranging from shareholders' agreements (49%), entry and exit provisions (28%), and provision for a third party mediator (24%) – though the presence of the latter may suggest that that particular business has experienced conflicts in the past. 32% have also instituted formal measures for assessing performance, which can be the result of bringing in professional managers who would need such appraisal, or evidence of the need for an objective process to manage underperforming family members out of the firm.

Across our respondents as a whole, 79% had some sort of mechanism like this in place, which rises to 84% for second + generation businesses, though it is possible that many of these mechanisms are very rudimentary, and there is no way of knowing how effective they are likely to be should an actual conflict arise. Indeed, we suspect that some family businesses are seriously underestimating the degree of conflict that the next transition point will generate, and would benefit from a greater understanding the best practice governance measures they might take now to mitigate it.

The benefits of listing: a Hong Kong perspective

One interesting finding from our survey was the fact that many more family businesses are listed in Asia, in comparison with firms of a comparable size elsewhere in the world. So we asked three prominent family businesses in Hong Kong about their experience of the listing process, and what benefits it can bring to the governance and management of a family firm.

Tom Tang, Managing Director, Asia Pacific Region, TTM Technologies

"The transition to a listed company is quite dramatic. As a private company, everything is quite easy. You can change direction, you can invest in products that have a much longer time horizon and in much more riskier projects. After you become a public company, these decisions have to be justified because you will be asked questions about their returns by the fund managers. Being a public company helps us because most of our customers are large companies which would not buy from a private company. Some actually require US listing because they need their suppliers to be Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank-compliant. And being a public company gives you other options. You can issue shares and bonds, neither of which are really available to a privately-held company. It does give you more flexibility."

Henry Tan, CEO, Luen Thai Holdings

"I'm very proud that we made the decision in 2004 to turn the family business into a public listed company. Not only does this bring in the additional capital we need for the business, it also demands a specific governance framework which supports better family governance as well. I would encourage all family businesses to get a public listing whenever they can. It helps ensure a proper structure between the shareholders, the management, and the business and makes each of these roles clearer."

Cheung Kit, Chairman, EVA Precision Industrial Holdings Limited

"The process of preparing for a listing can help you achieve greater clarity about management responsibilities within the business, which can also prevent potential conflict. In my company, my two brothers and I agreed on the allocation of shares in the period leading up to our IPO. We also mapped out a clear set of roles and responsibilities and the process for making collective decisions."

A unique social contract:

Are governments supportingfamily firms?

Some of the world's largest corporations began life as family businesses, and in the years since Rémy Martin bottled his first brandy or William Procter founded his soap and candle firm, the relationship between governments and firms like this has changed radically. As part of our survey we asked family businesses whether they feel valued by their governments, and what more they think should be done to support them.

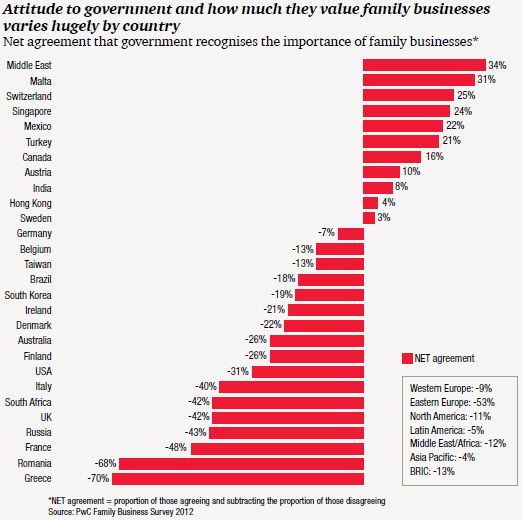

Family firms feel under-valued and overlooked

Our results suggest that regardless of their size, sector or market, family firms are proud of the economic contribution they make, and yet many feel this is overlooked or underrated by their own governments. Firms in markets like Turkey, Switzerland, Mexico, India, Malta and Singapore generally agree that their government values their sector, but this positive sentiment was outweighed overall by the number of respondents who considered that theirs does not – South Africa, the UK, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, and Greece were the most negative here.

Real support – or benign neglect?

Feelings run even higher when it comes to the action governments are taking – or not taking – to support family firms. Only three markets (Singapore, Turkey, and Malta) agree that their government is doing everything it can to help them, and there was overwhelming dissatisfaction from countries such as Australia, Denmark, France, Romania, the USA, Italy, South Africa, Russia, and Greece.

Indeed, a number observed that their government takes unfair advantage of one of characteristics of the family firm that governments always claim to value: other corporations can threaten to re-locate if they aren't given tax breaks or other incentives, but there's no need for governments to make the same effort for family businesses, because their strong local ties mean that they are highly unlikely to move to a more advantageous jurisdiction.

So what are family businesses looking for?

This divides into general measures, and specific demands. Family businesses – like all businesses – want to see a reduction in red tape, a more stable economic environment, low interest rates, a more flexible labour market, further incentives for employment and training, a more consistent tax and regulatory framework, and investment in infrastructure.

"Private companies must grow and increase their impact on the economic and political environment. They must be better represented within the institutions that define Russia's economic strategy and political views" (Russia)

"I think family businesses are critical to the Irish economy. We have seen time and time again where multinationals have pulled out of Ireland and moved to Asia or wherever, and that is a decision that's made on the basis of bottom line. Traditionally family businesses can't make that decision" (Ireland)

Family businesses also want to see more targeted support for their sector and measures specifically designed to help firms like theirs evolve and grow. First among these, unsurprisingly, is tax. Family businesses are broadly united in their desire for a simpler and more supportive tax regime, especially when it comes to capital gains and inheritance tax – they want governments to make it easier and less costly to pass their business to the next generation. All too often the value added by one generation is all but wiped out by the tax that has to be paid by the next. This is why the German government, for example, has amended the inheritance tax payable on the transfer of a business so that the amount due reduces significantly, or can even be eliminated altogether if the assets remain in the family for five years, and certain wage bill criteria are met. On the other hand, there are some market observers who argue that tax breaks of this kind can allow family firms to be insulated from outside input, and that in some cases the needto raise extra capital to pay inheritance tax would force under-performing firms to bring in new investors and new skills, which might result in a better balance on the management team.

Family businesses are also concerned to see more financial incentives and tax reliefs for start-ups, additional grants and incentives to support R&D and investment in new technology, improved access to long-term finance, and more training and support tailored to the needs of the family firm, which includes mentoring and networking, and help with succession planning, conflict resolution, and international expansion. The latter need to focus in particular on helping family businesses understand the different cultural, commercial and regulatory environments they will face in specific markets overseas.

"[We would like to see] consultation and training in succession planning, tax incentives and ownership incentives, improved tax laws, so as to make it easier to pass the business on without capital gains tax – we have capital gains tax here which can be pretty shocking" (Australia)

"Family businesses in Germany pay the lion's share of duties and taxes whereas the big corporations relocate to other countries" (Germany)

"In the future family businesses will operate more like multinational corporations. Although the decision-making will still be in the hands of the family, a family business will have to behave more like a global corporate company. I am already following this model. Family and global businesses will converge going forward and this will be a big change" (Middle East)

In Singapore, for example, the government has a number of high-profile initiatives designed to help entrepreneurs and small businesses, one of which focuses on supporting them to make the transition from domestic to international. This includes helping them identify the issues they may need to address, and giving them expert advice in making the first steps. In fact, there are so many incentives in Singapore that family businesses are turning to firms like PwC to help them identify those which are the most suitable for their own circumstances – a manufacturer, for example, might be eligible for over 90 separate schemes.

In other markets there is almost no help for family businesses, and in some cases support systems exist, but are under-used, or inadequately publicised. An obvious conclusion to draw here is that family firms need to take responsibility for ensuring that they do their own homework, and make the maximum use of all the resources that are available. An example would be Enter the Panda, which is an Anglo-Irish company based in Beijing, which helps small firms start doing business in China and Asia Pacific.

Likewise family businesses can do much more to lobby on the policy issues that affect them and campaign more collectively for greater support. Again, this is already happening in some markets – notably in Germany, Scandinavia, Spain and Italy. There is an enormous untapped opportunity for international cooperation between networks like this to share best practice and learn from proven good ideas. For example, the Family Business Network is now running a very promising new scheme which allows younger family members from one business to take short-term internships at another family firm, often in a different region or business sector. There are already examples of such Next Generation internships spanning markets as diverse as Brazil and the US, and Finland and Switzerland.

A checklist for government action

- Is your tax regime as supportive as it could be for family firms?

- Are there grants and incentives designed to meet their specificneeds, whether in innovation,R&D, or new technology?

- Is there more you could do to help them obtain long-term finance for expansion?

- What are you doing to help them access export markets?

- What support do you offer on training and skills?

- Do you have agencies that facilitate networking, mentoring and partnerships with multinationals?

- Is there a national strategy for supporting and developing family businesses to grow domestically and internationally?

- And finally, is the support you offer adequately publicised?

Conclusion

"I think that family companies will experience a renaissance. I think that it will be modern again to be a family company" (Denmark)

"It's the only sustainable business model" (Italy)

In the title of this report we call the family business a resilient model for the 21st century, and the results of this year's survey bear that out. However, the picture is not black and white, and our research suggests that the distinctive strengths of the family firm could be further enhanced by accessing new skills and international experience.

We believe family businesses and other corporates have much to learn from one another and, indeed, the lines between them are already starting to blur. We need to create more constructive and positive environments in which businesses can collaborate, network and innovate, and governments could do more to help facilitate this. Governments could also do much more to ensure both economic and fiscal policy and domestic banking systems support family firms. It is worth noting that the EU is already focusing on three of the key areas we have identified through our survey, namely access to finance, eliminating bureaucracy and reducing the tax burden when businesses like these are passed from one generation to the next.

If there's one single message from this year's survey it's this: family firms are a vibrant and vital part of the global economy and can make an even more substantial contribution to growth and recovery if they're given the right support, at the right time.

Footnotes

1 PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.