Key Messages:

- The Cyprus bailout and Italian political stalemate are reminders of how fragile and fast-changing events can be in the Eurozone

- The Chancellor's latest Budget offered modest support to the economy in 2014-15, but rising public debt levels are a concern

- Japan has signalled a bolder, more radical monetary policy to boost growth, but this may not be appropriate for countries with higher inflation rates.

At a glance

- After a quiet start to 2013, the latest episode in the Eurozone crisis in Cyprus provided a reminder of how fast events can unfold there.

- The Cyprus bailout negotiations revived fears of a disorderly bankruptcy and Eurozone exit, because of the events leading to the bail-out (extended bank holidays), the unprecedented content of the agreed package (deposit-holders taking a hit) and the post-bailout side-effects (capital controls).

- Italy also remains in a fragile state and appears to face a political stalemate after the elections in February, casting doubt on the pace of economic reforms that need to take place.

- More positively, the Irish government successfully tapped into international bond markets in March. This was just over two years after Ireland was bailed out and shows the merits of implementing a credible economic reform programme.

- In the UK, the Chancellor used the Budget announcement to try to bolster confidence by announcing a number of business-friendly measures. These included a lower corporation tax rate, reduced National Insurance Contributions particularly for small businesses and increased infrastructure spending from 2015.

- We expect the measures announced in the Budget to provide some modest support for the economy in 2014 and 2015, although they are not large enough to have a major impact on the growth outlook.

- Also, even though the Chancellor said this was a fiscally neutral budget, figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) show that UK public debt is now set to rise to over 85% of GDP in 2016-17 before peaking, which is getting uncomfortably high.

- The Chancellor also announced changes to the remit of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). In this spirit, we have reviewed the global debate on monetary policy, where governments are asking their central banks what more they can do to promote economic growth.

- In Japan, for example, the government has raised the Bank of Japan's inflation target to 2% from 1% and encouraged them to do more to boost growth.

- However, Japan's case should be put in the context of its persistent deflationary environment (see Figure 2). This approach may be less appropriate for other struggling economies with higher inflation rates.

The return of the Eurozone crisis

Last month Cyprus stood on the brink of becoming the first country to leave the bloc before a last-minute deal saved the nation's banking sector and the government from bankruptcy. Meanwhile, Italian elections produced a stalemate, leaving Italy with a minority government that will struggle to vote policies through parliament without eventually returning to the polls.

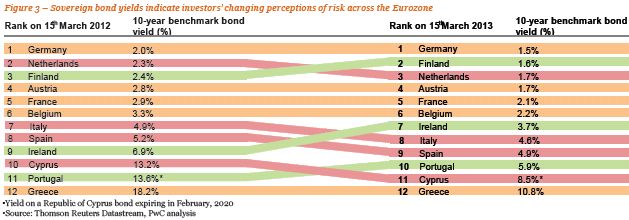

More uncertainty in the UK's largest trading partner is not what businesses need when attempting to export and invest in the region. However, firms should avoid a blanket approach to assessing the Eurozone's economic environment. Our analysis highlights that investor perceptions of credit risk, as measured by government bond yields, evolved markedly over the last year (see Figure 3 below).

In particular, investors' attitudes towards investing in Ireland and Portugal have improved, as their governments have got on with implementing tough structural reforms. Ireland can now borrow at a cheaper rate than Spain and Italy, where confidence that politicians can pass similar programmes has ebbed.

Cyprus is a reminder of how quickly events unfold in the Eurozone.. Table 1 on the right identifies some key milestones in the next two months for businesses to look out for that may signal turning points in investor sentiment.

UK Budget 2013: Sailing a Steady Course

In challenging economic times, the Chancellor needed to announce a confident, stable Budget based on sound, practical economic decisions that would send a message of confidence to businesses. So has he delivered on this?

A positive tone

We expected a Budget with a strong emphasis on supporting the UK being "open for business". The Chancellor did indeed talk about building the most competitive tax system in the world and of a desire to support the entrepreneurial spirit in the UK. He backed this up by announcing that corporation tax would come down to 20% and by giving more support for research and development (R&D).

He also announced an employment allowance for the first £2,000 of a company's National Insurance bill which will benefit all businesses, particularly small and growing businesses, wanting to take on staff.

One more thing he committed was to spend more than previously planned on infrastructure (by around £3bn a year from 2015 onwards) which could provide some medium-term opportunities for businesses in the construction sector. It could also help to close the "infrastructure gap" between the UK and the Asian Tigers (see Figure 4).

Supporting growth but debt target pushed back a year

Even though the Budget was presented as being fiscally neutral, the latest OBR forecasts show that the projected total public debt stock in March 2018 is now £103 billion more than expected at the time of the Autumn Statement in December. So the Chancellor is allowing the public debt stock to continue to climb, pushing back the date at which the debt ratio peaks by a further year to over 85% of GDP in 2016/17.

Overall, we expect the Budget measures to have a modestly positive impact on business confidence and growth in 2014-15, but they are not large enough to produce a major change in the UK economic outlook.

Japan is undertaking radical measures in pursuit of growth

For the first time in years, Japan is exciting the business world. After a decade where nominal GDP contracted and government debt doubled (see Figure 5), Japan's new Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, has shown renewed determination to get the world's fourth largest economy moving again. Abe's "three arrows" economic strategy consists of:

- a "bold" and expansive monetary policy;

- a "flexible" fiscal policy; and

- structural reforms to improve long-run potential GDP.

It is the first pillar that has captured worldwide attention. The Government has increased the Bank of Japan's (BoJ) inflation target from 1% to 2%, and replaced its Governor with a long-standing advocate of more aggressive monetary policy. As we discussed in our March edition, these moves have already been enough to weaken the Yen by 10% against the US$ since the start of the year.

But are central banks at the limit of what they can do to support economic growth?

As the need for budgetary consolidation continues to constrain the flexibility of fiscal policy, governments continue to lean on monetary policy to do more to support growth. Central banks are responding by considering ever more expansionary measures – from the Fed pursuing an explicit unemployment target to Mark Carney (the incoming Governor of the Bank of England) touting the merits of forward commitments to keeping monetary policy very loose (see quotations, Figure 6).

But, as the limits of current policy settings are reached, any further accommodation is likely to be a step into the unknown. Japan is at the very edge of this frontier: interest rates have been near-zero for 18 years and the BoJ is already on its eighth round of Quantitative Easing after becoming the first major central bank to pioneer the policy in 2001. In total, it has bought over ¥80 trillion of assets (equivalent to around 20% of its GDP) and purchases have been extended to commercial paper, corporate bond and ABS markets. Further options on the table may include negative interest rates, purchases of foreign debt or "helicopter money" (explicit monetary financing of government debt).

Further monetary accommodation poses both risks and opportunities for global businesses

Japan's struggle with deflation is relatively unique in the global context – most major economies are trying to limit price rises rather than spur them on. However, if "Abenomics" starts to show signs of stimulating the economy, other countries struggling to deliver growth may be tempted to adopt similar measures (as signalled by the review of the UK's monetary framework announced by the Chancellor in the Budget).

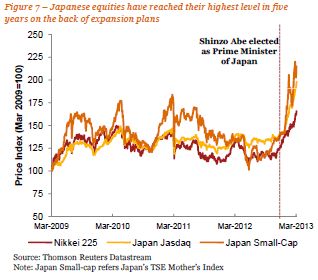

Any sustained monetary expansion could improve global business confidence: rising consumer sentiment is likely to bolster revenues whilst looser monetary conditions could lower financing costs. Equity indices in Japan have surged since Abe's election at Christmas on the back of optimism about corporate earnings and a weaker yen (see Figure 7).

But the risks are also pronounced. The big fear is that excess liquidity could leak into consumer prices, pushing up inflation. And a more general move to monetary expansion can quickly turn into a series of competitive devaluations, further exacerbating global inflationary pressures. Easy money can also distort outcomes in the real economy: for example, zombie companies can be kept on life support by low borrowing costs.

All of this means that, in a world of abundant central bank liquidity, businesses should take advantage of cheap financing sources in their capital raising plans, whilst at the same time continuing to focus their investments on generating fundamental value and boosting efficiency. They should not rely on cheap money continuing indefinitely.

PROJECTIONS

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.