Ushering in a truly circular economy, i.e. one that runs on products, components, and materials that are reused instead of discarded, requires more than the will to change one's behaviour. It takes real updates to how we approach the taxation of services and materials. Our last article looked at how stakeholders would feel the different VAT impacts of the resell model, one concrete circular business model. We would like this time to examine another circular business model, the product-as-a-service (PaaS) model. We'll look at the fiscal implications (both in terms of VAT and direct tax) for service provider, customer, and State.

What is the product-as-a-service model?

Do we actually need to own the products we use? That is the question that drives the performance economy. First studied by Walter Stahel in the late 1980s,1 the "functional service economy" (also called performance economy or service economy) introduced new business models where a company sells performance instead of goods—like mobility instead of cars. Today this is called the pay-per-use, subscription, or product-as-a-service model. It ranges from pay-per-week handbag usage, to pay-per-cycle washing machine usage, to pay-per-lux light usage. The objective is to maximise the value extracted from material resources, and to decouple economic growth from resource consumption. As such, it is one of the main schools of thought feeding into the concept of a circular economy. According to Jeannot Schroeder, managing director of +ImpaKT and contributor to this article, "this business approach is a real game changer for a more circular approach as all the of the environmental consequences stay with the producer."

Do PaaS models affect tax expenses?

While there are many arguments in favour of PaaS models, e.g. customer loyalty or cash flow predictability, the fiscal implications have not yet been fully studied. To study the tax impacts of such a business model, we might take the example of light-as-a-service.2 In this business model, a company (provider) sells the service light to another business (customer) instead of selling lighting as an asset. For this example, let's say the service is sold for a fee of €50 per year (excl. VAT), instead of as an asset sold for a one-shot price of €1,000. (It must be noted that this is a simplified example in which only the provision of the lighting is considered, and not the possible repair services or other related transactions).

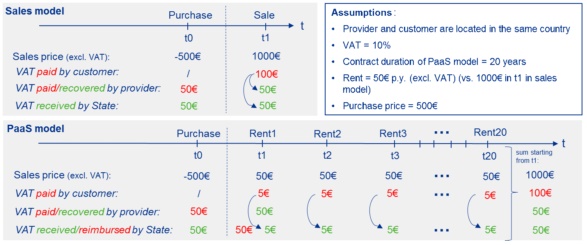

Let us start by looking the table below, which compares the VAT flows between the baseline scenario (the sales model) and the PaaS model.

In the traditional sales model, the provider purchases the equipment for €500 (plus €50 VAT). The customer then pays a price of €1,000 (plus €100 VAT, assuming a VAT rate of 10%). For the provider, the transaction is always VAT neutral. That the provider paid €50 VAT on the purchase of the asset (or its materials) puts him/her in a tax credit position and allows him/her to net €50 of the €100 VAT paid by the customer. The State receives the remaining €50.

In the PaaS model, the customer pays a yearly service fee of €50 over a 20-year contract. This means that, instead of collecting €100 VAT in year 1, the provider collects €5 annually. VAT legislation allows the provider to be compensated by the State immediately in the first year for the VAT paid on the purchase of the asset: in this case, the provider gets €50 back. The result is that the State pre-finances the VAT and only gets it back in €5 instalments over 20 years.

When looking at the VAT flows over the 20 years, the total paid/received is the same in both models. However, the distribution of the flows over the timeline changes.

In this example, the PaaS model is favourable to the customer because he/she can spread the VAT expenses out over a longer period of time, which can make a big difference. The PaaS model is unfavourable to the State, however, which must pre-finance the VAT to compensate the provider but can recover the remaining VAT only gradually. For the provider, the transaction is VAT-neutral in both models. Ultimately this example shows how the "time value" of money3 can make a circular business model more or less attractive for the actors involved.

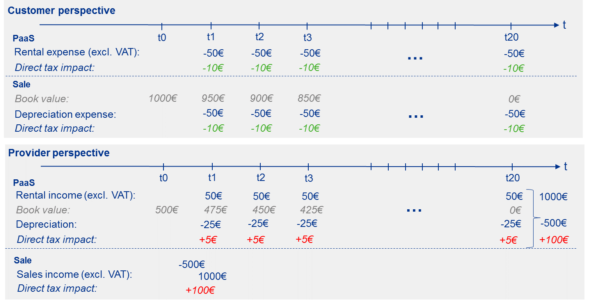

To determine the impact on direct taxes, we need to look at the income flows and depreciation expenses in both scenarios. We'll assume a fictional income tax of 20% and a depreciation life of 20 years for lighting equipment.4

From the customer's direct tax perspective, it makes no difference whether a yearly rental expense of €50 is paid or a yearly depreciation expense of €50 (€1,000 over 20 years) is taken.5 Both result in an annual reduction of the income tax by €10. For the provider, however, there is a difference: while in the sales model the provider pays direct taxes on the €500 profit (€1,000–€500) immediately, in the PaaS model the profit amounts to the yearly rental income minus the yearly depreciation expenses spread over 20 years. Although the total income tax paid will be the same in both models (€100), their being spread out over 20 years makes the PaaS model favourable for the provider and unfavourable for the State from a direct tax perspective.

In summary

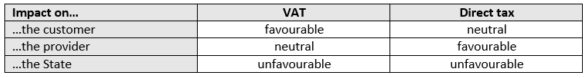

In this specific case of moving from a linear sales model to a PaaS model, the tax implications are the following:

What does this imply?

It would appear that there are no immediate tax barriers for businesses engaging in PaaS models—neither in terms of VAT nor of direct taxation.

That being said, the analysis also seems to suggest that the PaaS model may be unfavourable in cash flow terms for the State. However, our example provides only a very reductionist view of the situation. It does not consider the positive indirect effects created for society and the State. For example, a case could be made suggesting that PaaS models would generally include maintenance and repair services, thus increasing the yearly service fee and thereby the income tax collected. Additionally, activities related to the PaaS model like repair, reconstruction, and recycling are labour-intensive and can therefore increase labour tax income for the State. Moreover, positive side effects like new jobs and reduced pollution should also be kept in mind.

This case study shows that tax policy is worth thinking through carefully if it is to successfully incentivise the transition towards a circular economy without having negative side-effects. Deeper analyses and simulations will bring more definitive answers—we have barely scratched the surface in this blog post.

Footnotes

1 Stahel (1987): "Economic strategy of durability, elements to valorize the service life of goods as a contribution to waste prevention", Bankverein Book Nr. 32, November 1987, Basel.

2 Light-as-a-service is, for example, sold by Philips in the Netherlands.

3 €1,000 today is not worth the same as €1,000 in 5 years, due to inflation and potential interest earned. This is the meaning of the "time value" of money, one of the core principles in financial theory.

4 In this example, the contract duration equals the depreciation life and the yearly rent equals the yearly depreciation expense for the customer. This has been chosen on purpose in order to make a direct comparison of direct taxes possible.

5 This is true in this simplified example. In real life, the provider can of course choose a yearly rent higher or lower than the depreciation expense for the customer. However, one can assume that it would be close in order to be attractive for both parties.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.