INTRODUCTION

'Nuclear new build' in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has a very different meaning from 'nuclear new build' in any country with existing nuclear power capacity. For MENA states, the task is not simply one of designing and building a new nuclear power plant; it involves designing and building the entire legal and physical infrastructure associated with the development of nuclear power capacity – in most cases from scratch. This guide explains the key steps and challenges confronting each MENA state that is embarking on this process.

REGIONAL CONTEXT: NUCLEAR POWER NEW BUILD IN MENA COUNTRIES

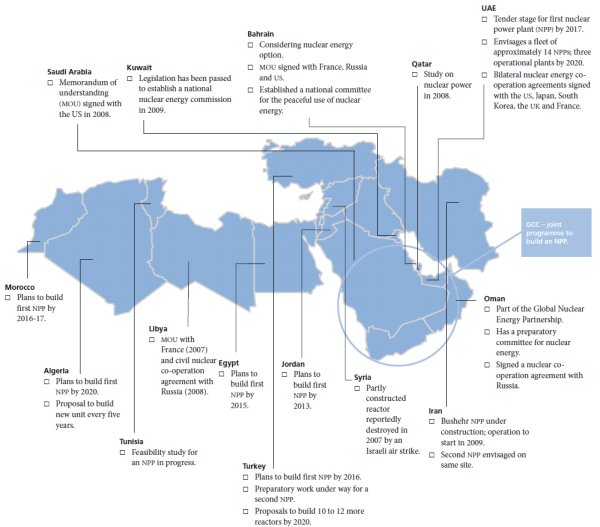

Virtually every MENA state is actively considering the development of a nuclear power programme. According to a recent report by the International Atomic Energy Association (the IAEA), 51 countries currently without nuclear power capabilities expressed an interest in developing nuclear power capabilities in 2008. Of these, 17 are from the Middle East and the Pacific and 13 are from Africa.

For some states, such as Turkey, Jordan and Egypt, nuclear power plans have long been in the making. In 2007, the IAEA, at the request of the Gulf Co-operation Council (the GCC), produced the Pre-feasibility Study of Nuclear Power for Electricity Generation and Desalination in the GCC Region. It examines the economic feasibility of including nuclear power in the region's future electricity-and-desalination mix. The study's findings and recommendations were formally endorsed by the GCC in December 2007 and, since then, the GCC has been further studying the possibility of a joint GCC initiative for nuclear power.

|

Key Drivers Of MENA Interest In Nuclear Power

|

Each country will need to undertake a series of key steps to develop a domestic nuclear power programme and each will confront a number of significant challenges.

|

Challenges For Nuclear New Build In MENA Countries Without Existing Capacity

|

INTERNATIONAL NUCLEAR COMMUNITY AND LEGAL REGIME

|

Steps Necessary For Proper Engagement With The International Nuclear Community

|

The international community has developed an extensive apparatus of international bodies, nuclear principles and formal multilateral instruments. Established in 1957 as a specialised agency of the United Nations, the IAEA has become the pivotal intergovernmental agency concerned with co-operation in the nuclear field. Oman and Bahrain joined in 2009, taking its membership to 150 states. IAEA membership is a prerequisite to obtaining international political credibility for the development of a domestic nuclear power programme. States, suppliers, commercial banks and other lenders use IAEA standards and policies as the key sources for their own standards and policies.

The dominant aspect of the international nuclear regime is commitment to non-proliferation. The IAEA oversees the domestic implementation of the NPT and enters into bilateral and comprehensive safeguards agreements with member states to enable it to verify that each state is living up to its international undertakings not to use its civilian nuclear power programmes to develop nuclear weapons. Safeguards agreements have been signed by all MENA states, which must co-operate fully with the IAEA.

There is also a body of key international instruments, most of which were developed under the auspices of the IAEA, that should be ratified by states embarking on domestic nuclear new build. These instruments embody and expand on the key principles of international nuclear law, and cover issues from nuclear safety to co-operation in the case of a nuclear accident and, importantly, civil liability for nuclear damage.

Entry into bilateral agreements is also common and their usefulness for MENA states embarking on new build reflects the way in which nuclear technical and human resources have been limited to countries with historical nuclear generation capacity. These bilateral relations are always underpinned by a commitment to non-proliferation and may include agreement to provide assistance with: reactor development; training, infrastructure and human resources development; implementation of appropriate safeguards and nuclear security and protection arrangements; and exchange of scientific and technical information. For MENA countries without significant technical expertise, these bilateral relationships will prove invaluable.

|

Key International Legal Instruments

|

DOMESTIC LEGAL REGIME

The starting point for a domestic nuclear legal regime is ratification of the international legal regime. An internationally compliant domestic legal regime will be essential to secure international political acceptance of a nuclear power regime, to encourage bilateral relations with countries with technical and human resources, to attract suppliers and operators and to obtain financing.

|

Key Components Of A National Nuclear Law Based On The International Nuclear Regime

|

In developing and implementing a domestic legislative structure, states should draw on international expertise – different models exist, but they may not be suitable for every country's needs. The precise content of a domestic nuclear law will, of course, depend on the particularities of each state, its existing legal regime and the nuclear programme to be embarked on. For example, Jordan plans to exploit its significant uranium resources so its legal regime will need to address the full range of activities involved in the nuclear fuel cycle, including extraction, mining and milling and enrichment of nuclear fuel. The development legislative structures must follow the IAEA's Basic Safety Series, which is intended to complement international conventions, industry standards and specific national requirements on the proper protection of people, property and the environment from nuclear risks.

A central component of any domestic legal regime is civil liability for nuclear damage. The effects of a nuclear accident can be transboundary and of extreme magnitude. An international regime has been developed to address the specific nuclear risks and national legislators should ensure that domestic regimes are aligned with the relevant international nuclear conventions on the key issues of:

- channelling liability to the operator;

- limitation of liability in amount and time;

- the right balance between the operator's liability and the level of financial cover; and

- matters of jurisdiction and enforcement of foreign judgments.

The approach to these issues will be crucial to attracting suppliers, operators and lenders to embark on nuclear power projects in MENA. In particular, the adoption of the above principles will be required to obtain nuclear-related insurance for what would otherwise be unquantifiable and unlimited liability. The nuclear liability conventions require a level of congruence between the operator's liability and the maintenance of insurance or provision of other financial security.

|

Key Challenges For MENA Countries Wishing To Develop A Legal Regime For Nuclear Power

|

DEVELOPMENT OF PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Matters such as siting, effects on the environment, transportation, waste management, connection to the electricity grid and grid capacity to supply electricity to the market are important considerations. The reactor itself must be supported by additional physical infrastructure, such as:

- a spent-fuel storage facility;

- a waste storage facility;

- a water plant;

- an on-site electrical distribution system;

- health and safety facilities;

- calibration laboratory facilities; and

- safeguard and emergency equipment.

The development of these components can be the responsibility of the state or can be developed by the reactor suppliers, depending on the project's structure and procurement options to be adopted.

FINANCING

The risk profile for nuclear power plants is unique. The key risks associated with nuclear power influence the financing available and include:

- Political Risk: investors will be concerned that there may be a change of policy towards nuclear power;

- Legal And Regulatory Risk: countries need a stable national legal and institutional framework, with strong and consistent regulations governing all aspects of nuclear power. Otherwise, successfully financing a nuclear power plant will be impossible;

- Planning And Development Risk: the need for governmental and public support in the planning phase; the licensing regime's complexity and the time required to obtain (and risk of not obtaining) a licence; onerous conditions to which a licence may be subject;

- Construction And Cost Overrun Risk: the risk of delays and cost overruns during the capital-intensive construction phase, in an industry with a record of both;

- Market Risk: the ability to compete with other fuels, especially in the GCC (although this may be limited if pricing comparisons are done on a netback basis (a key finding of the IAEA/GCC study)); and the risk of changing prices for all inputs and for electricity, which is particularly acute for nuclear power because of its long construction time and high capital expenditure requirement;

- Liability And Safety Risk: accidents, should they happen, are likely to be far more wide-ranging and long-lasting than with other sorts of fuel, whether on-site or during the transportation of fuel or waste; and the insurance market, particularly with respect to a nuclear plant in the GCC, may have limited capacity;

- Waste Storage And Disposal Risks: finding an appropriate location may prove challenging, and has cost implications. Although shared facilities could be an option, this solution raises issues of transportation of irradiated materials and compliance with international conventions on transboundary movement of dangerous substances;

- Decommissioning Risks: the cost of decommissioning is extremely difficult to estimate and so sizing the financial capacity to do this, if it will not be borne by government, is equally complex, although what is certain is that the cost is likely to be very high. Various economic models and government-sponsored programmes have been developed to deal with decommissioning costs, including the establishment of government-supported decommissioning funds; and

- 'First Of A Kind' Risk: the fact that any domestic nuclear plant would be the first in each MENA country would mean that the importance given to all the above risks would be higher than would be the case for any subsequent nuclear development.

The allocation and mitigation of the various risks between the public sector and private sector participants will be essential to a successful financing. As with all financings, the above risks should be allocated to the party best placed to manage them.

Government Financing

Nuclear power development requires government support. Governments control regulatory practices and have the ability to put in place economic and institutional policies to support a nuclear power plant financing, including national electricity pricing arrangements and the implementation of a streamlined licensing regime that can reduce the risk of project delays due to regulatory processes or pre-approval for site selection and pre-certification of reactor design. Direct government involvement may take the form of equity participation, asset ownership, assumption of certain risks, loan guarantees (a sovereign guarantee of 100 per cent of the debt or a debt facility to cover cost overruns) and incentives such as tax incentives and feed-in tariff structures (as is being implemented in Turkey).

Balance-Sheet Financing

Financing a nuclear power plant on a company's balance sheet would strain the balance sheet of all but the largest companies. A corporate financing would ordinarily be carried out by the utility taking the power from the plant: the same company would build the plant and then sell the power to consumers. Most of the MENA electricity utilities are government-owned so any attempt to carry out a balance-sheet financing would in effect be a government obligation.

Private Sector Finance

Nuclear power projects have high capital costs (60 per cent of the overall project cost) and high sensitivity to construction delays, cost overruns, inflation and interest rates. Traditionally, suppliers and sponsors of existing plants have financed them with an underpinning of government sponsorship and traditional cost-of-service rate regulation that essentially assured full cost recovery from captive or guaranteed markets. Limited recourse financing – better known as project financing – relies on a contractual framework specific to a project to raise financing for that project. In the case of a nuclear power plant, the key contract would be a long-term power purchase agreement.

Potential Lenders

Potential lenders to a nuclear plant include:

- commercial banks;

- export credit agencies (ECAs); and

- multilateral agencies (MLAs).

Although many ECAs and MLAs have written or in-practice policies under which they will not lend to nuclear projects, the participants in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Arrangement on Guidelines for Officially Supported Export Credits (better known as the OECD Consensus) have recently agreed on the 2009 Sector Understanding on Export Credits for Nuclear Power Plants, which could indicate a recognition that ECAs will be required to undertake increased export financing in this sector. Commercial banks, on the other hand, are more willing to lend to nuclear projects, although this statement is subject to the overriding observation that the current state of the financial markets means that any project finance is subject to tight limits.

CONCLUSIONS

In the context of global interest in nuclear power, it will be imperative for MENA states that wish to embark on nuclear new build to start developing the required legal and physical infrastructure immediately. To do this, MENA states must liaise closely with those who have the international expertise necessary to ensure that an internationally compliant, comprehensive and workable regime is put in place.

Footnotes

1. International Status and Prospects of Nuclear Power, IAEA publication, December 2008.

2. It is not necessary to sign all instruments relating to nuclear liability.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.