Private equity investors are increasingly looking to the education sector to make sizeable investments, with high growth expectations driven by increasing demand for education and the introduction of new, innovative models of education.

In addition, the wider markets offered by the South East Asia region provide a significant opportunity for overseas institutions to enter into collaboration activities with local players.

In short, the education market in South East Asia is ripe for investment as a result of:

- increasing affluence with a growing middle class prioritising spending on education;

- competing priorities for government spending, leaving the door open for private investors as the public sector seeks additional investment to respond to demand;

- population growth and a preference for private schooling;

- increasing demand for tutoring and enrichment programmes where parents have total choice and there is less pressure on pricing; and

- increased mobility and migration, with a widening expatriate community resulting in greater demand for international curricula and institutions.

In Vietnam, for example, 2015 has seen British University Vietnam start construction on a US$70m campus in the Hung Yen province to provide training on international business administration, marketing, accounting and finance to 7,000 students and Singapore's KinderWorld Education Group launch the Pegasus Mixed Educational Development in Danang. In addition, Ho Chi Minh City has seen the launch of the U.S.-Pacific University, a US$150m project and branch of the American Pacific University. 2014 saw Advent International acquire Singapore's Learning Lab, a provider of academic enrichment and tutorial services for primary, secondary and integrated-program students and Abraaj invest in Thailand's KPN Academy, an out-of-school education service provider.

The South East Asia education sector

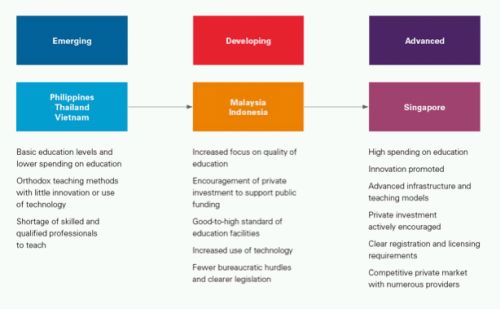

In South East Asia, the education sector is still in various stages of development1:

Language learning centres and childcare providers have been the traditional targets for private equity investment in the region, for example Navis established the Indonesian arm of English-language education business Wall Street Institute in 2007 and disposed of it to Pearson in 2012. The secondary and tertiary education markets were more difficult to access, with sellers generally heavily-invested in the institution and demanding more aggressive valuations. The South East Asia region has, however, seen increased opportunity here in recent years, a trend that should continue, particularly through collaboration with U.S. schools.

Government spending on education across South East Asia has historically been lower than developed markets such as the United States and the United Kingdom. Yet the school-age population in the region stands at around 128 million, nearly twice that of the United States. With the education sector in the region currently being valued at around US$110 billion per year, compared with US$1.43 trillion in the United States, clearly the opportunities for growth are significant.2

So where do the opportunities lie?

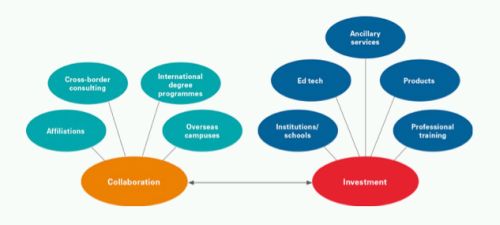

Collaboration

Several international universities have established branch campuses with a sponsoring entity in South East Asia, whilst others have established collaboration arrangements with other institutions and organisations. Once a formal collaboration framework is in place, investors can provide various services as consultants, from the selection of degree programmes, to curriculum design, to research and development. The South East Asia region has seen a significant amount of interest: the UK's Nottingham University operates a campus in Malaysia and Singapore is home to a number of U.S. universities including Yale-NUS College (a collaboration between the National University of Singapore and Yale University) and Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School (a collaboration between Duke University and the National University of Singapore).

The growing and diverse domestic and expatriate populations of South East Asia provide a highly attractive opportunity for international institutions looking to expand and increase their brand awareness, with a different risk and capital outlay profile to direct investments.

Direct investment

Institutions are facing increasing pressure to improve operational efficiency and reduce expenditure by using the private sector to provide ancillary services that were traditionally delivered in-house. Opportunities for direct investment in South East Asia include:

- Education infrastructure: i.e., the schools and institutions themselves. This can cover school tutoring and enrichment centres as well as pre-schools and K-12 schooling. Different jurisdictions will bring different affordability criteria which need to be taken into account in the context of market size;

- Technology or "Ed tech",

comprising:

- instructional technology - classrooms are more interactive than ever before and technologies enabling assistive and adaptive teaching techniques as well as classroom management tools will increase in importance;

- learning management systems – the expansion of online offerings in the region will increase the popularity of software applications for student administration, documentation, reporting and tracking;

- social learning networks – increased stakeholder inclusion in teaching through student-teacher-parent interaction will require more effective collaboration technologies;

- assessment management systems – with increased scrutiny on student performance in fee-paying institutions, technologies that track results and provide detailed analysis of trends and performance will increase in prevalence; and

- e-learning – many schools in South East Asia are introducing tablets in the classroom and learning and training will need to be adapted to suit this method of delivery.

- Ancillary services, comprising:

- marketing and recruitment – focusing on increased domestic and international enrollments requires specialist marketing techniques and strategies, often met by private sector providers;

- administration – institutions can cut back on the costly IT services and infrastructures by using companies that provide administrative solutions and achieve their own economies of scale; and

- distance learning – offering courses online enables institutions to reach broader audiences.

Attractions and challenges

The education sector in South East Asia provides unique attractions for a private equity investor and international institutions looking to expand. Up-front registration and course fees, paid in advance, provide a source of regular income. In South East Asia, a liquid expatriate market leads to multiple turnover of students and rapid technological changes have opened up new options for investment (for example, through online platforms and distance learning). The sector is also protected from broad economic trends and enjoys a high-level of fragmentation.

However, collaboration and direct investment in education are not without their challenges:

Collaboration

- Complex regulatory and local law requirements (employment, immigration, IP, real estate, licences/permits, taxation, privacy and data security)

- Potentially complex due diligence on proposed partners

- Institutions often lack the commercial experience to meet the requirements of formal investors

- Potential brand dilution/erosion

- Anti-bribery and corruption issues

Direct investment

- Restrictions on foreign ownership

- Capital intensive

- Geographical scale is challenging, particularly cross-border

- Low deal volume requiring innovative approaches

- Difficulties enhancing revenue generation and reducing costs of delivery

- Anti-bribery and corruption issues

Direct investment – key issues

Pick your market

- Certain countries, such as Indonesia and the Philippines, see a high proportion of private sector coverage in higher education whereas in Vietnam, the public sector continues to dominate.

- Domestic income levels may also be a factor with lower incomes in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam and higher incomes, in relative terms, in Singapore.

Foreign ownership

- In Indonesia, there are significant restrictions on investment in formal education, i.e., schools teaching the national curriculum or an international curriculum. The law and regulations curtail and restrict not only the ability to invest but also the ability to undertake a school as a profit-generating business.

- There are also strict rules on foreign investment in tertiary education, which involve obligatory collaboration with local institutions and the prioritization of local faculty and staff for employment. In addition, foreign universities can only operate in Indonesia on a non-profit basis.

- Schools providing non-formal education (such as English language schools, secretarial colleges and computer schools) may be established through limited liability companies or where foreign investors establish a foreign investment company with a local partner having to own at least 51% of the shareholding of that company.

- In the Philippines, the ownership/establishment and administration of educational institutions is subject to an ownership limit of 40% for foreigners.

- In Vietnam, the regulations for foreign investment are quite vague and generally focused on Vietnamese education providers. This can present obstacles when foreign institutions are looking to invest.

Local risk factors

- While many of the 'usual' risk factors for investing in education will apply to South East Asia, there are certain specific issues to consider, including risks attached to local currencies. Fees may be collected in local currency, which, in certain South East Asia jurisdictions, can be highly volatile.

- Thorough due diligence on any potential local partner is also crucial, a factor which may lead to increased transaction time.

The regulatory environment

- The regulatory environment in South East Asia is as diverse as the counties that make up the region.

- Singapore, for example, has very clear legislation governing the registration of institutions with the Ministry of Education as well as minimum requirements imposed on teaching and other staff.

- Certain other jurisdictions have less clear regimes and there tends to be no consolidated law governing foreign investment. Instead, the relevant framework is derived from a number of different laws. Primary legislation can be generally drafted, leaving its precise application open to interpretation which, combined with inconsistent application, can lead to concerns over judicial interpretation, and impacts on value including the ability to protect an investor's intellectual property and brand.

- Key points include:

- whether there is consolidated formal legislation in place governing private investment in education;

- the registration or accreditation requirements for investors and teachers;

- the annual reporting and filing requirements;

- what public funding is available for private education;

- the regulations regarding fee structures; and

- what local elements must be taught as part of the curriculum.

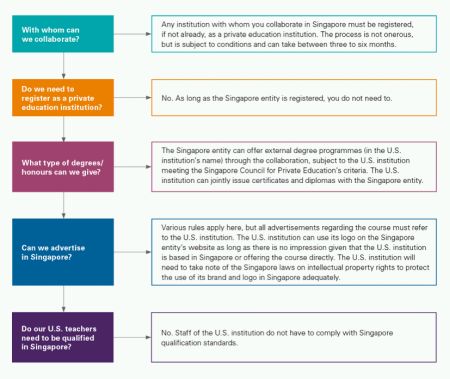

Case study – U.S. collaboration in Singapore – the potential

The Singapore Government is generally favourable towards Singaporean educational facilities collaborating with foreign institutions. As regards the United States, the Singapore Minister for Education and the U.S. Secretary for Education signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 2012 to enhance collaboration between the two countries in this important area. However, there are a number of regulations that govern the ability to collaborate in education in Singapore. The local legal regime, while established and robust, requires expert navigation across all aspects, including licencing, governance and corporate structure (including whether a legal entity should or must be formed), immigration, IP, employment, taxation and real estate. A U.S. institution must also consider U.S. regulatory requirements, including, for example, accreditation and rules related to participation in the federal student financial aid programs.

Whilst regulations provide that no person in Singapore can offer private education in Singapore unless registered as a private education institution, this does not prevent U.S. institutions from collaborating in Singapore. Set out below are some key questions and responses to be considered by a U.S. institution seeking to collaborate with an educational institution in Singapore:

Conclusion

The education market in South East Asia is growing fast, with many diverse opportunities for investment and collaboration. While rates of return in the education sector in South East Asia can be significant, a thorough understanding of the market, the regulators involved and the venture itself is required to avoid any pitfalls.

Footnotes

1. Source: Al Masah Capital

2. Source: Asian Venture Capital Journal, "Southeast Asia education: Top of the class?", 11 February 2015.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.