On 5 December 2017, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court (the "Court") published on its website a new decision in the field of international arbitration (the "Decision")1 wherein it annulled an award on jurisdiction of an ad hoc arbitral tribunal with seat in Zurich.

In the Decision, the Court came to the conclusion that the three-member arbitral tribunal wrongly accepted jurisdiction as the agreement between the parties would not sufficiently express an intention of the parties to derogate from state court jurisdiction and to agree on arbitration.

1 Facts

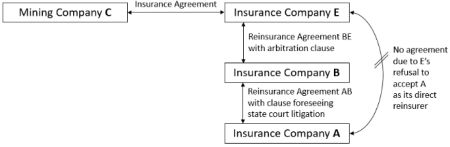

The dispute in question centres around the reinsurance agreement between the two insurance companies A and B ("Reinsurance Agreement AB"), concluded in 2010.

The Reinsurance Agreement AB had the following background: the mining company C insured its risks with the insurance company E. The insurance company E then concluded a reinsurance agreement in this respect with insurance company B ("Reinsurance Agreement BE"), and B again concluded a reinsurance agreement with A - the Reinsurance Agreement AB.

B only got involved in this insurance relationship as the insurance company E refused to accept A as its direct reinsurance company. Prior to E's refusal of A as its potential direct reinsurer, A had submitted to E an offer with an insurance slip and a contract endorsement, wherein reference was made to E's conditions, which contained an arbitration clause foreseeing arbitration at an ad hoc arbitral tribunal with seat in Zurich. But given E's refusal, this contract was never concluded.

The two reinsurance agreements between A and B as well as between B and E respectively contained diverging dispute resolution clauses. The Reinsurance Agreement AB foresaw state court litigation whereas the Reinsurance Agreement BE referred to the arbitration clause contained in E's condition, i.e. ad hoc arbitration in Zurich.

Simplified, the situation presents itself as follows:

In 2015, B initiated proceedings against A at an ad hoc arbitral tribunal seated in Zurich requesting payment of approximately CAD 9 million. A objected to the arbitration invoking that the arbitral tribunal would lack jurisdiction due to the fact that the Reinsurance Agreement AB foresees state court litigation.

The ad hoc arbitral tribunal limited the arbitration proceeding first on the question of jurisdiction and rendered on 15 February 2017 a partial award accepting jurisdiction. A then filed an action for annulment with Court

2 Considerations

After assessing and affirming the admissibility of the action for annulment regarding the partial award on jurisdiction, the Court summarized its case law regarding the requirements for an annulment of a wrong ruling on jurisdiction. Only a few points of this case law will be outlined hereinafter.

The interpretation of an arbitration agreement follows the general principles for contract interpretation. First, the mutual subjective intent of the parties has to be established. If such an intent cannot be established, the arbitration agreement has to be interpreted by applying the principle of good faith, i.e. the meaning that parties could and should have given to their reciprocal manifestations of intent.

When interpreting an arbitration agreement, their legal nature must be considered. In particular, it is to be taken into account that the therein inherent waiver of the access to state courts heavily restricts the access to appeal proceedings. Such a waiver cannot be assumed easily, wherefore a restrictive interpretation of an arbitration agreement has to take place in cases of doubt.

However, should the interpretation of the arbitration agreement show that the parties indeed excluded the dispute from state jurisdiction and agreed to submit the dispute to an arbitral tribunal, utility considerations shall apply, i.e. the agreement is to be interpreted in a way, if possible, that the arbitration agreement persists.

In the case at hand, no explicit arbitration agreement was included in the agreement between the parties of the arbitration. To the contrary, the Reinsurance Agreement AB contained a clause foreseeing state court litigation in cases of disputes.

The Court then explained why the assessment of jurisdiction of the ad hoc arbitral tribunal was wrong and why neither the arbitration agreement contained in the Reinsurance Agreement BE nor the one referred to in A's offer with an insurance slip and a contract endorsement to E are of relevance for the dispute between A and B.

Therefore, there was no valid arbitration agreement in place between the parties and the ad hoc arbitral tribunal wrongly accepted jurisdiction.

3 Conclusions

The arbitral tribunal was bending over backwards to achieve a result which from a practical standpoint might have been feasible but legally remained untenable. The Decision as such is - to paraphrase Charles Poncet - "of limited interest" - only.

The Court just reconfirms its long-standing policy in deciding on jurisdictional disputes in arbitration: first, the pendulum swings on the one side, requiring a manifest waiver of the access to state courts and, once such waiver is established, then the pendulum swings back on the other side, providing the agreement to arbitrate a broad area of application (in favorem arbitrii).

The Decision was rendered by a delegation of three judges only, thus revealing that the Court itself did not consider the Decision to be of particular relevance. Nevertheless, the Decision provides an up-to-date analysis of the relevant case law of the Court in this respect and is therefore helpful to any practitioner confronted with jurisdictional issues in arbitration.

But several questions remain open: what about the tribunal's fees and the costs of the arbitration proceedings which have been commenced ultimately in vain? Assuming that the tribunal did not allocate the costs in its partial award will it now issue a termination order in which it allocates the costs? But, can it do so at all or will a state court have to rule on this issue?

And what about the potential liability of the ad hoc tribunal? Is their potential liability to be treated differently regarding an award on jurisdiction annulled by the Court than an award annulled due to a violation of due process? The arbitration institutions generally provide for an exclusion of liability of the arbitrators - such as in Art. 40 ICC Rules and Art. 45 Swiss Rules - but what if in this ad hoc arbitration the arbitral tribunal failed to expressly exclude its liability?2

Enclosure: BGE 4A_150/2017 of 4 October 2017

Footnotes

1. BGE 4A_150/2017 of 4 October 2017, in German.

2. Nadia Smahi, The Arbitrator's Liability and Immunity under Swiss Law, ASA Volume 34, No. 2016, pp. 876, and ASA Volume No. 35, No. 1, 2017, pp. 67. Further Martin Bernet and Jörn Eschment, SchiedsVZ 2016, volume 4, pp. 189.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.