This Economic Outlook has three sections. The first covers recent dynamics and short-term outlook for the world economy. The second presents a discussion of the context and conduct of US monetary policy in recent years and in the short term. The final section reviews recent international trade statistics and trade negotiations.

Economic Growth: The Road Ahead Still Bumpy

Recent World Economy Dynamics

Global growth for 2013 is turning out a little slower than both the actual rate for 2012 and the projected rate for 2013 in the Bennett Jones Spring 2013 Economic Outlook. Growth in the United States so far this year has been somewhat lower than we projected last spring, largely because fiscal drag has been greater than we assumed. As projected, Europe continued to contract, Chinese growth edged down on average, and growth in other emerging markets has been lackluster. But there are now solid indications that some sustainable pick-up in the pace of global activity may well have begun. It would largely originate from somewhat faster growth in advanced economies since the pace of advance in China and other emerging economies is likely to remain below that achieved in 2010-12.

Recent economic indicators point to accelerated growth in the UK and Japan, a slowly improving (albeit highly fragile) euro-area economy, and relatively robust private-sector growth in the US offset by increased fiscal drag. Renewed optimism about growth prospects in the US and expectations that US monetary authorities would soon add less stimulus to the economy by "tapering" bond purchases led this summer to an abrupt increase in long-term interest rates in the US with a consequent tightening of financial conditions in the US and the rest of the world, especially emerging economies with large current account and budget deficits.

This is the background for our projection that some acceleration in world economic growth would occur in 2014 and 2015 and that much of the acceleration would come from advanced economies. The two-speed global economy we saw in 2011-12 is slowly beginning to give way to more balanced global growth with emerging market and advanced economies growing at more similar rates in 2014-15.

Short-Term Outlook: 2013-151

Global growth in 2013 will likely come very close to the three percent recorded in 2012 and projected for 2013 in the Bennett Jones Spring 2013 Economic Outlook. However, a somewhat larger than expected contribution will come from advanced economies and a correspondingly smaller one from emerging economies. As expected last spring, projected world economic growth should reach the higher but still subdued rate of 3.5 percent in 2014. We project a slight improvement to 3.6 percent in 2015 as advanced economies gain some momentum, partly as a result of less fiscal drag and less private sector deleveraging. China is likely to experience somewhat slower growth in the next two years, partly as a result of efforts to rein in credit expansion and achieve more balanced growth. Other emerging economies would grow only moderately faster than in 2013 for a variety of reasons including slower Chinese growth, relatively flat commodity prices and an externally induced tightening of financial conditions. The expansion of emerging economies remains solid enough (along with improved growth in advanced economies) to support prices for oil and minerals at current levels.

Growth in the US is projected to fall to 1.5 percent in 2013 from 2.2 percent in 2012, partly as a result of slower than anticipated growth in personal consumption and business investment and larger cuts in government spending. In fact, fiscal drag as measured by the change in overall fiscal balance increases from 1.4 percent of GDP in 2012 to 2.5 percent in 2013, partly reflecting automatic spending cuts that started in March (the so-called sequester). The partial shutdown of the US government in October is assumed to cut annual output growth by 0.1 percentage point in 2013 as a result of the induced fiscal tightening and associated loss of confidence. Real GDP growth accelerates to 2.6 percent in 2014 and 3.2 percent in 2015 supported by several factors:

- Solid pace of consumption and rapid growth in housing investment, supported by gains in employment and personal wealth and by household re-leveraging;

- Diminishing drag on growth from fiscal policy as budgetary retrenchment (as a share of GDP) is projected to be cut by half in 2014; and

- Some pick-up in business investment in response to better growth prospects, with lots to cash available for spending.

The euro area should resume growth at a tepid pace of one percent or so per annum in the next two years following a decline in activity in 2012 and 2013. Household and bank deleveraging and fiscal consolidation continue to weigh on aggregate spending, but to lesser extent than in previous years (fiscal tightening cut by half to 0.5 percent of GDP in 2014) while a pick-up in global demand promotes export growth.

Growth in China, on the other hand, falls in the 7-7.5 percent range over the next two years from 7.8 percent in 2012 and 9.3 percent in 2011 as a slowdown in investment growth and the dampening effect of the renminbi appreciation in recent years on net exports are only partly offset by continued urbanization and a gradual firming of household consumption. Chinese authorities are not likely to try counteracting a moderate slowdown in aggregate demand as it would compromise the transition toward more balanced (and sustainable) growth.

As expected last spring, Canadian growth remains subdued at 1.6 percent in 2013 compared with 1.7 percent in 2012. We project growth to rise to 2.1 percent in 2014 and 2.3 percent in 2015, mainly on account of some strengthening in business fixed investment and exports as global growth improves and confidence rises. In particular, faster growth in US industrial production is expected to support stronger growth in Canadian exports of raw materials and semi-finished products. This being said, the projected strengthening of business investment and exports would be less pronounced than in many other forecasts and for this reason Canadian aggregate growth in this outlook would be marginally weaker than in a consensus forecast. In any event, it is considerably slower than expected last spring not only in absolute terms but relative to US growth. In part our relative pessimism for Canada reflects our expectations that weak cost competitiveness would continue to dampen growth in exports and inbound foreign investment even as the Canadian dollar trades within a lower range of US$0.91-$0.98 over the next two years. The lack of cost competitiveness afflicts not only the manufacturing sector but also many service industries and some resource industries as well. Prospects for gains in competitiveness through faster productivity growth or slower compensation increases are highly uncertain. At the same time as the lack of cost competitiveness constrains growth of exports and investment, a high level of household indebtedness and higher mortgage interest rates constrains growth in personal spending.

With projected rates of real GDP growth barely faster than the expected potential output growth rates of about two percent over the next two years, slack in the Canadian economy would diminish only gradually. The economy would still be in a state of excess supply at the end of 2015. Consequently, although rising progressively, inflation would likely remain below the two percent target to the end of 2015 and pressure to raise the overnight policy rate would not likely be felt before late in 2015.

Risks to Outlook

The global and Canadian outlooks for 2014-15, while improved from 2013, are somewhat less robust than might be expected on the basis of past economic upswings. Deleveraging, particularly in the government sector, continues to constrain growth in advanced economies while structural imbalances slow the rapid expansion in emerging markets. But even our outlook for moderate 3½ percent growth in the global economy is somewhat fragile as downside risks to growth likely continue to dominate upside risks.

The downside risks mostly relate to:

- The emergence of adverse political developments (e.g., backlash against adjustment, lack of progress toward banking union) in a euro area that has still to cope with a fragmented financial system, high public debt and structural problems;

- Weaker growth in China if household consumption fails to pick up enough while investment falls relative to GDP, with adverse consequences for commodity prices and global trade; and

- Unexpected consequences of the unwinding of US unconventional monetary policy, which may bring financial market turbulence and excessive tightening of financial conditions worldwide (see the next section, US Monetary Policy in Recent Years and in the Future).

On the other hand, US growth may rebound more sharply than expected, growth in Europe and Japan might surprise on the upside, and the prospects for expanded world trade may provide some upside risk (see final section, Trade Developments).

Conclusion

- Global growth to accelerate in 2014-15 but to still moderate rates. This acceleration would originate from advanced economies.

- Fiscal drag to continue as governments make further progress in reducing their deficits, but at a diminishing rate so that the negative impact on economic growth would gradually diminish over the next two years.

- In advanced economies, excess supply would diminish only gradually over the next two years. Hence, inflation would remain benign (below or near target) to the end of 2015 or longer.

- Given the economic outlook for the advanced economies, their central banks would continue to pursue accommodative policies over the short term, although the degree of stimulation is likely to be reduced in several countries. As growth strengthens and central bank bond purchases start diminishing, long-term interest rates would rise further in 2014 and 2015, but in a measured way. Central banks in advanced economies are unlikely to begin to raise their policy (overnight) rates from current very low levels before the end of 2015.

- Weak cost competitiveness would continue to constrain output in Canada even though the Canadian dollar is expected to trade within a lower range of US$0.91-$0.98 over the next two years. Needed structural adjustment is neither easy nor fast and requires commitment to innovation, productivity enhancement and compensation restraint by both industry and government.

- Over the medium and longer terms, coping with the effects of population aging on potential growth, pensions and the demand for health care is a challenge for Canada and other advanced economies.

US Monetary Policy in Recent Years and in the Future

Long-term interest rates in the US, Canada and many other countries have risen and exhibited considerable volatility since last April, with large collateral effects on equity prices and exchange rates. This turbulence has arisen from market reactions to upbeat news on US employment and official policy pronouncements concerning the prospects of adjustment in US monetary policy via a tapering of bond purchases by the Federal Reserve. Although these market reactions have been overblown, it is hardly surprising that upcoming changes in US monetary policy would draw much attention worldwide since they are bound to have important effects on a broad spectrum of asset classes (e.g., bonds, stocks and currencies) and across regions of the world, and therefore significant implications for the global economic outlook. The specific questions that markets and policy makers around the world have at present with respect to US monetary policy are:

- When would the "tapering" of bond purchases by the Fed begin?

- For how long would the overnight policy rate remain near zero?

In order to have a proper perspective on these questions and their potential answers, this section provides a discussion of the context and conduct of US monetary policy in recent years and in the short term.2

Prior to the financial crisis, the central banks of advanced economies pursued objectives of price stability (as in Canada) or maximum employment compatible with price stability (as in the US) by relying on a well-understood tool: changes in overnight policy rates, which financial markets would reliably transmit to longer-term interest rates. The resulting change in financial conditions, including possible variations in the exchange rate, could be counted on to bring real spending in line with potential output and hence gradually align actual inflation with target inflation.3 The latest financial crisis, however, greatly exacerbated the severity of any typical business cycle downswing. Current and expected sharp declines in output and inflation prompted central banks to slash short-term interest rates to near zero quickly, although the precise speeds of reduction varied across central banks. By December 2008, the US Federal Reserve had reduced the federal funds rate to near zero, thus as low as it could go, but judged that further monetary accommodation was needed nonetheless to stem the risks of a protracted slump and consequent price deflation. With short-term rates stuck at their zero-bound, additional monetary stimulus would have to be provided through lower real long-term interest rates. To achieve maximum reduction in long term rates, the Fed relied on two unconventional tools: forward guidance and bond purchases.

Forward guidance entails managing market expectations of future policy rates. It has been successfully used not only by the Fed, but also by the Bank of Canada and other central banks. Central Banks could lower real long-term interest rates by reinforcing expectations that short-term rates will stay low for a long time. The Fed started using forward guidance in mid-December 2008, when the FOMC declared that it "anticipates... exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for some time." This message was extended and modified a number of times but in December 2012 the Fed shifted from time guidance to conditional guidance in order to increase the clarity of its message about the conditions under which it would leave its policy rate near zero. Thus, the FOMC stated that it "currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate [0 to ¼ percent] will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6½ percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's two percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored." More recently, on August 1, 2013, the Bank of England provided similar conditional guidance linking Bank rate and asset sales to a seven percent unemployment threshold, subject to conditions regarding projected inflation, medium-term inflation expectations and financial stability.

The second unconventional tool used by the Fed to lower real long-term interest rates consists in expanding its balance sheet by printing money to purchase bonds.4 These operations lower long-term bond yields by signaling that a central bank is ready to go out of its way to keep interest rates low for longer, by reducing the supply of bonds for trading thereby raising their prices and reducing their yields, and by inducing investors to "reach for yield", thereby accepting lower returns for riskier assets (e.g., corporate bonds). Starting in March 2009, the Fed has implemented three rounds of bond purchases or quantitative easing in addition to the Maturity Extension Program, which sold short-term in exchange of longer-term Treasuries. Currently, the Fed is buying $45 billion of Treasuries and $40 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) each month. All in all, the Fed currently carries an additional $3 trillion of Treasuries and agency securities on its balance sheet relative to early 2009.

Long-term interest rates trended downwards over most of the period from late 2008 to the summer of 2012. For instance, 10-year US Treasury bond yields generally fell from an average of 3.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008 to a low of 1.6 percent in the third quarter of 2012. As suggested by empirical studies, this decline partly reflects the combined effects of forward guidance and bond purchases. Various bond purchase programs are estimated to have reduced US 10-year bond yields by between 90 and 200 basis points.5 Weak growth prospects also depressed long-term interest rates through expectations of low short-term rates and low inflation for longer.

Conditioned by a prolonged period of exceptional monetary accommodation, traders reacted violently in May and June of this year to upbeat news on employment, which confirmed a positive outlook for the US economy, and to policy pronouncements suggesting the mere prospects of a tapering of bond purchases by the Fed starting in the fall or early winter of 2013. They probably realized also that long-term interest rates had fallen to unsustainably low levels.6 Thus, traders quickly tried to sell US Treasury bonds. A spike in US bond yields erupted, spilling over across asset classes and regions of the world. In the US, yields on 10-year Treasuries rose from a low of 1.7 percent in early May to a high of 2.9 percent in early September. This led to sharply rising mortgage rates, a fear that the recovery of the housing market would be aborted, and a fear that tighter credit to business would slow the recovery. To alleviate the resulting tightening of financial conditions, which they judged to be premature, the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England, among others, issued forward guidance to the effect that monetary policy would remain very accommodative as long as macroeconomic conditions warrant it. Nevertheless, it is only with the FOMC's unexpected announcement on September 18, that it would keep its bond purchase program intact for the time being, that a small retreat in bond yields from their earlier peak did occur. In early October, the yields on 10-year Treasuries and 10-year Canada bonds were still above their low of 1.7 percent in early May by over 90 basis points and 80 basis points respectively.

In hindsight, it seems that traders and Fed watchers underwent a sudden, major shift in their expectations concerning the prospects for monetary policy reversal. Their focal point was upbeat news on employment combined with Fed pronouncements on near-term prospects for tapering rather than the fundamental model of Fed intervention. Ongoing expectation adjustments have led to much increased volatility of bond yields since last April.

The fundamental model of Fed intervention is a variant of the blueprint used by central banks that have an inflation target, like the Bank of Canada. In setting monetary policy, the Fed seeks to bring inflation in line with its longer-run goal of two percent and employment in line with assessments of its maximum level. These objectives are clearly complementary in the current situation, in that considerable slack in the economy currently depresses both inflation and employment below their target levels. Given that monetary policy changes affect the amount of slack in the economy and its impact on inflation and employment with lags, the Fed would consider starting to withdraw monetary stimulus when its medium-term outlook for the economy, which incorporates all the relevant current economic data, suggests that on current policy there are material risks that inflation exceeds its target between one and two years ahead by a significant amount. These conditions are not likely to materialize before a while. Yet a market-induced rebound in long-term interest rates this summer effectively tightened financial conditions This is likely one of the reasons why the Fed decided not to start tapering in September, contrary to market expectations.7

Going forward, the Fed will have to decide on a sequence of two sets of events: first, when to diminish the additional stimulus provided by bond purchases, i.e., when to start tapering bond purchases and for how long, account taken that the announcement of tapering is likely to prompt some rise in long-term interest rates and hence tighten financial conditions; and second, later on, when to start normalizing monetary policy, i.e., start raising the overnight policy rate with the explicit aim of withdrawing stimulus.

With respect to tapering, forward guidance suggests that as the US economy gives signs of significant and sustainable progress in reducing slack in the labour market and the economy more generally, it will be appropriate to start reducing bond purchases and eventually to stop them altogether. Based on the Fed's recent economic projections, on those just released by the IMF and on private forecasts, it seems probable that the US economy will give indications of improving enough in the first half of next year (assuming no protracted fiscal imbroglio) to warrant a reduction in the pace of bond purchases. As the prospects for stronger growth become more entrenched, the tapering of bond purchases become more imminent to market participants and expectations that policy rates would be raised within two years or so become more firmly held, US long-term rates would be expected to start rising before any action taken by the Fed. All in all, one could see yields on US 10-year Treasuries reaching 3-3.5 percent by end-2014 and perhaps 3.5-4 percent by end-2015, compared with about 2.5-2.6 percent in October 2013. Moving roughly in tandem, 10-year Canada bond yields could rise to over three percent by end-2014 and nearly four percent by end-2015, from about 2½ percent in October 2013.

Further down the road, as unemployment falls and inflation approaches 2½ percent, monetary policy will need to be normalized, i.e., the policy rate (the target federal funds rate) will need to rise from near zero. Given the substantial amount of slack in the US economy at present and therefore prospects of tame inflation for several years, and given that the FOMC intends to maintain the current Fed funds rate "at least as long as" unemployment remains above 6.5 percent and possibly a lower level than that to take account of other measures of labour market tightness, it seems probable that the FOMC will not start raising the federal funds rate before rather late in 2015. Of course, if in the meantime Fed projections of inflation for the next year or two were going to outstrip its two percent target by a significant margin, then monetary policy would be tightened earlier than expected through rises in the overnight policy rate irrespective of labour market conditions. This, however, looks improbable in light of the current amount of slack in the US economy and current prospects for growth in the short term.

To conclude, based on our outlook for US economic growth, employment and inflation, we expect that:

- The Fed will start tapering bond purchases probably in the first half of 2014 with modest increases in long-term interest rates taking place during 2014 and 2015; and

- It is unlikely that the Fed will start increasing its policy rate (i.e., the target federal funds rate) before late 2015.

Given our weaker outlook for Canadian growth over 2014 and 2015, we expect that the Bank of Canada will follow – not lead – Federal Reserve policy rate increases.

Trade Developments

Trade Statistics

Consistent with somewhat reduced expectations for global economic growth, WTO economists are now predicting that world trade growth in 2013 and 2014 is likely to be slower than previously forecast. They estimate 2013 growth of 2.5 percent (down from the 3.3 percent forecast in April), and 4.5 percent in 2014 (down from 5.0 percent), but they say conditions for improved trade are gradually falling into place.8

A key reason for this is that demand for imports in developing economies is recovering at a slower rate than expected. Also contributing to this relatively weak performance is a decline in imports of the EU from the rest of the world by two percent in the first half of 2013 compared to the same period in 2012.

Newly appointed WTO Director-General Roberto Azevêdo commented, "Although the trade slowdown was mostly caused by adverse macro-economic shocks, there are strong indications that protectionism has also played a part and is now taking new forms which are harder to detect."

In July, the outgoing Director-General delivered to WTO Members his final trade monitoring report9 covering the period mid-October 2012 to mid-May 2013. Carefully weighing his words he concluded:

Overall, this report presents a reassuring assessment of the main trends in terms-of-trade measures implemented over the period from mid-October 2012 to mid-May 2013. However, while there is no need for alarmist or dramatic announcements, trade-restrictive measures continue to be adopted and the stock of existing measures remains high. History has taught us that protectionist pressures can be generated by stubbornly high levels of unemployment in many countries, persistent global imbalances, and macroeconomic concerns. And these, I am afraid, are all part of the global economic reality all our countries face today.

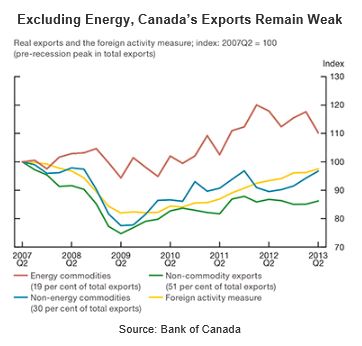

Canada's merchandise trade picture for the first eight months of 2013 shows only modest gains over the previous year of 1.4 percent in exports and 0.7 percent in imports.10 As shown in the chart below taken from the October 2013 Monetary Policy Report by the Bank of Canada, the volume of non-commodity exports have not kept pace with foreign activity in the last few years, consistent with a significant negative effect from earlier losses in cost competitiveness.

Trade Negotiations

The last few months have seen a steady increase in the momentum for negotiating new trade agreements. The US and the EU launched the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) on June 17. On October 8, leaders of the countries participating in the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations committed to an early and ambitious conclusion to these efforts. On October 18 Canada and the EU announced they had reached agreement in principle on an ambitious comprehensive economic and trade agreement. On July 30, President Obama publicly asked Congress for fast-track authority to negotiate new trade agreements.

These developments and others like them will help generate confidence that governments can manage the challenges of trade in the 21st century and should also help governments withstand protectionist pressures.

While there remain grounds for concern about the current trade situation with continuing protectionist pressures, the picture appears brighter than a few months ago. World trade is recovering, albeit more slowly than earlier hoped. There are tentative signs that WTO Members may be able to produce a modest positive result at December's Ministerial conference in Bali. There is also growing momentum and signs of progress in broad efforts to negotiate new trade agreements on a regional or plurilateral basis. In addition, the international trade rules have largely worked in the current crisis in holding protectionist actions at bay. The big future challenge will be trying to broaden the disciplines emerging from current negotiations into rules of global application.

WTO

WTO Members selected an able, experienced, senior Brazilian trade diplomat, Roberto Azevêdo, to replace Pascal Lamy as WTO Director-General on September 1. Azevêdo has wasted no time in engaging Members in the effort to try to salvage a useful result at the 9th Ministerial Conference in Bali in December. This engagement is at all levels – from G20 Leaders in St. Petersburg to the ambassadors of all WTO Members in Geneva. He starkly told WTO Members at a General Council meeting on September 9 that "the future of the multilateral trading system is at stake."

Speaking of the WTO's failure to conclude the Doha negotiations he concluded:

... the perception in the world is that we have forgotten how to negotiate. The perception is ineffectiveness. The perception is paralysis. Our failure to address this paralysis casts a shadow which goes well beyond the negotiating arm, and it covers every other part of our work.

Azevêdo's efforts are strongly supported by the membership. Indeed President Obama's new US Trade Representative, Michael Froman, traveled to Geneva to make the keynote address11 at the recent WTO Public Forum. He praised Azevêdo's efforts and added his view of what a successful meeting in Bali could mean:

... let me say how strongly the United States supports the new intensification of work under our new Director General. In a few short weeks, he and his team have created and managed a process that has given this Membership a chance to succeed.

Bali has the potential to be a vital step towards the WTO creating something new, something that can lead to other new opportunities – to innovation in our approach to multilateral negotiations.

Meanwhile, a flurry of negotiations at various levels – plurilateral, regional and bilateral – have been underway. An overview of these negotiations is provided in the annex to this section.

Harper Government's Ambitious Trade Agreements Program

The Canadian government has finally shown it can achieve real results in its ambitious trade negotiations program. The October 18 agreement in principle on a massive trade deal with the EU is a big achievement in its own right but will also add to the credibility of Canadian negotiators in other negotiations Canada is pursuing.

Here is a brief look at the status of the Canadian government's key free trade negotiations.

Canada EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

The agreement in principle with the EU appears to be one that is broader and deeper than even the NAFTA. This is a major achievement. While the key political decisions to make an agreement have been made on both sides, there remain many important details that still need to be completed before the two sides can initial an actual agreement. The negotiating teams will also need to conduct a legal review of the text and have it translated into 22 EU languages in addition to French.

The ratification procedures in Canada will involve the federal government and the provinces. In the EU, approval of the European Parliament is needed as well as the parliaments of the 28 member states. However, it is expected that once the European Parliament approves the agreement it would be put into force on a provisional basis. It will probably take up to two years from now to bring the agreement into effect.

Both Canada and the EU claim that this agreement is of a higher standard than other FTAs they have so far concluded. The agreement may well set a new standard for what will be included in subsequent agreements including the TTIP and the TPP.

Canada Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA)

The fourth round of these important negotiations will be held in Ottawa in mid November. A continuing challenge for Canada will be keeping the attention of Japan as it engages in TPP and other important negotiations mentioned above.

Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)

Leaders of the TPP countries announced on October 8 that "our countries are on track to complete the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations." The pace of negotiations is intense. However, given the different structures of the economies of the participating countries and quite different views on key outstanding issues we do not think a final agreement is likely before late next year at the earliest. This is a very important negotiation for Canada. Obviously the agreement can open up new opportunities across the Pacific. Perhaps even more important, the three North American countries are now negotiating with each other for the first time in 20 years, on the same issues that are already incorporated in the NAFTA. The potential de facto changes to the NAFTA will bear careful watching.

Canada Korea FTA

These negotiations have been given a boost at a bilateral meeting earlier this month between Prime Minister Harper and President Park Geun-hye of Korea. The two leaders were reported to have discussed innovative ways of completing the negotiations in the near future. This would be an important achievement because Canada has fallen behind the US and the EU who already have FTAs with Korea. The resulting discrimination against Canadian goods is causing damage to many exporters for whom the Korean market is important.

Korea has shown new interest in completing FTAs with Canada, Australia and New Zealand. A motivating factor here is the fact that the TPP, in which Japan is now engaged, would open the markets of these three countries for Japan and create de facto discrimination against Korean companies.

ANNEX: Global Summary of Sectoral, Regional and Bilateral Trade Negotiations

Plurilateral Negotiations in Geneva

Negotiations are underway on two plurilateral sectoral agreements in Geneva which could make important contributions to trade liberalization and rule making.

Trade in Services Agreement (TISA)

These negotiations involve an initial group of 21 WTO member governments, who together represent almost two-thirds of global services trade. These negotiations offer a real prospect to establish new disciplines that will go beyond those of the Agreement on Trade in Services already contained within the WTO. The participants would like to see other WTO members join the negotiating effort but the objective of getting significant concessions from the major developing countries may make that objective difficult to achieve.

Information Technology Agreement (ITA)

This agreement among 70 participants covers about 97 percent of world trade in information technology products. The ITA provides for the complete elimination of duties on IT products covered by the Agreement.

At their recent meeting, APEC ministers pushed for an early conclusion to these negotiations, perhaps even before the Ministerial Conference in Bali in December.

The major economic powers continue to press forward with a massive program of competitive trade liberalization. The following provides a brief update on some of the most strategically important of these initiatives.

Regional Negotiations

TransPacific Partnership (TPP)

Spearheaded by the US, these negotiations involve 12 countries on both sides of the Pacific including Japan, Canada and Mexico. On October 8, leaders of the TPP countries declared:

We see the Trans-Pacific Partnership, with its high ambition and pioneering standards for new trade disciplines, as a model for future trade agreements and a promising pathway to our APEC goal of building a Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific. We are encouraged by the growing interest in this important negotiation and are engaging with other Asia-Pacific countries that express interest in the TPP regarding their possible future participation.

Pushed by the Obama Administration, the TPP partners had agreed to finish the negotiations by the end of 2013. That date will be missed. Efforts to conclude quickly may set up tensions with those who want an ambitious outcome. In particular, this may well create problems inside the US. Big business wants a major result while the Administration might be tempted by a quick "win". The US cause was not helped by the fact that President Obama did not go to the APEC meetings because of the budget crisis in the US.

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP)

This far reaching bilateral effort between the US and the EU was launched in June. The first negotiating session was in July but the second one had to be postponed because of the US government shutdown. There have been a number of high-level meetings to discuss how to address some of the more difficult challenges in the negotiations, notably those in the regulatory area.

Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)

This negotiation would join the 10 ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) countries and six other partners (Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea) in one collective FTA. ASEAN includes Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. The second round in these negotiations was held in Australia in September; the third round is scheduled for Malaysia in January. The participants have established the objective of completing the negotiations by the end of 2015.

Bilateral Negotiations

China, Japan and South Korea

The second round of negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) among these countries was held in Shanghai in August. A third round is expected in Japan perhaps before the end of 2013. Skeptics suggest putting a deal together among these partners may be difficult. Hedging their bets, South Korea and China are also engaged in a bilateral FTA negotiation, a seventh round of which was held in China in September.

Japan and the EU

Japan and the EU have just completed the third round of negotiations on a Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).

Footnote

1 The October 2013 Monetary Policy Report (MPR) by the Bank of Canada exposes quite well the main features of the Canadian and global economic outlooks in the short term. The MPR is generally written in non-technical language and contains much more detail than in this brief outlook section. It is worth reading.

2 This discussion focuses on policies aiming at achieving the Federal Reserve mandate of maximum employment and price stability. After the onset of the financial crisis, the Fed implemented a number of programs designed to restore the proper functioning of financial markets and intermediation. These are not discussed here.

3 It is important to realize that monetary policy affects the real economy and inflation with variable lags over time, generally within one to three years.

4 The Bank of England and the Bank of Japan have also undertaken bond purchases, but not the Bank of Canada. It is worth noting also that bond purchases per se are an old tool in the arsenal of central banks. Open-market purchases and sales used to be the conventional tool employed by some central banks to affect commercial bank reserves and interest rates in an earlier era.

5 International Monetary Fund, Unconventional Monetary Policies – Recent Experience and Prospects, April 18, 2013, p. 15.

6 It could be argued that bond yields were unsustainably low in the spring in light of the sharply negative term premium they embedded. Much of the rise in bond yields since then would reflect an increase in the term premium. Indeed, the bond sell-off in the summer mainly shifted bond yields at long maturities while short bond yields continued to be anchored by continued low policy rates.

7 Moreover, the decision appears to have been sound in light of the subsequent events on the fiscal front and the fact that the observed US unemployment rate decline probably overstates the improvement in the labour market.

8 WTO press release PRESS/694 of September 19, 2013

9 http://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news13_e/trdev_19jul13_e.htm

10 http://w03.international.gc.ca/Commerce_International/Commerce_Country-Pays.aspx?lang=eng

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.