Abstract

The Comesa 2018-2019 report is encouraging: accounting for 46% of African FDI inflows, with 33% of all projects being greenfield, 38% of all cross-border M&A sales and raking in USD 19 billion investment income. Comesa's value and contribution to regional trade is therefore established. Likewise, the business case for competition rules fifteen years on, seems to have been sustained. Competition regulations are important because they set minimum standards for free and effective competition whilst discouraging anti-competitive conduct. Further, cross-border business regulation builds capacity and develops cost-effective strategies for monitoring elusive trade barriers like market monopoly. This is a brief review of Comesa transactions during the active years of the Comesa Competition Commission (2013-2019). This paper aims to advise on technical aspects of the regulatory regime for investment advisors operating within the Common Market. *The full version of the article provides an analysis of selected case studies in antitrust, consumer protection and M&A matters and was presented at the Norton Rose Fulbright-Jackson Etti & Edu event on the introduction of the new Nigerian anti-trust law entitled "The Changing Landscape: Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Act".

Background

What is "Comesa"? Comesa, popularly known as the "Common Market", is an African Regional Economic Community ("REC") formed in 1994 that facilitates trade relations between mostly Southern and East African countries. It accounts for a significant portion of intra-African trade and business co-operation in about twelve (12) sectors. All business is managed by various integrated institutions and agencies such as the Comesa Court of Justice (Khartoum, Sudan), the Comesa Competition Commission (Lilongwe, Malawi), the Comesa Trade and Development Bank (formerly and popularly known as the PTA Bank - Ebene, Mauritius), the Comesa Clearing House (Harare, Zimbabwe) and the African Leather and Leather Products Institute (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia).

The Comesa Competition Commission was established and made fully binding on Member States in 2004, but only fully operationalised in 2013. This means that cross-border businesses operating within this sub-region must conform to the rules of fair play as enshrined in the founding Treaty. Business transactions such as mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures as well as advertising are under scrutiny in a bid to regulate anti-competitive practice in the market. Comesa and the EU are the only regional bodies that enforce cross-border competition law.

The Comesa Competition Regulations (the "Regulations") are the substantive rules meant to foster healthy business competition by preventing restrictive business practices (in both public and private entities) as well as safeguarding the interests of consumers in the Common Market. The regulatory framework covers four (4) aspects, Merger Control Regulation, Consumer Welfare, Abuse of dominance and Anti-competitive Practices. Comesa jurisdiction is automatically triggered once a business transaction crosses into the border of another Member State, subject to regulations of course.

Transactional review

|

Comesa FDI Income v Africa: |

FDI inflows increased by 3.6% from US$ 18.6 billion in 2016 to US$ 19.3 billion in 2017 and accounted for approximately 46% of Africa's FDI inflows in 2017; |

|

Comesa FDI dominating countries: |

Egypt (44.4% total) and the dominant sectors include Petroleum (64.6%), Services (11.4%) and Manufacturing (10.4%). Ethiopia (18.6% total) and the dominant sectors include Real estate, Manufacturing, and Construction dominated at 92%. |

|

Comesa FDI dominating sectors: |

Overall, Manufacturing, Oil and gas, Real estate, Construction and Financial services are the most attractive sectors in the Common Market. |

|

Comesa greenfields v Africa |

The Common Market accounted for 33% of all greenfield projects in Africa. Total number of greenfield projects were 219 and shared as follows; Egypt (24%), Kenya (23.7%), Ethiopia (11%) and others 41.3% |

Fig 1 (Comesa, 2018)

Sector performance

Comesa focuses on the following sectors: Agriculture; Alcohol & Non-alcoholic Beverages (FMCG); Banking & Finance; Construction (Real estate & Infrastructure); Energy (Power); Hospitality; ICT & Communications; Insurance; Mining; Petroleum (Oil & Gas); Pharmaceuticals and Transport logistics.

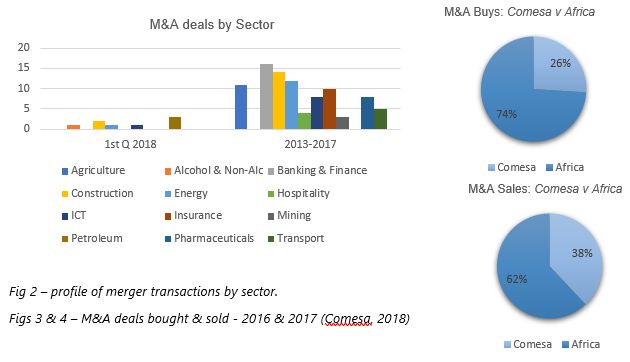

The target sectors for investment are currently Manufacturing, Petroleum (Oil & Gas), Construction (Real Estate & Infrastructure) and Banking & Finance. As shown below, the dominant sectors in M&A transactions within the first quarter of 2018 were Petroleum, Construction and ICT, whilst Banking & Finance, Construction and Energy (power), were leading between 2013 and 2017.

Case statistics (2013-2019)

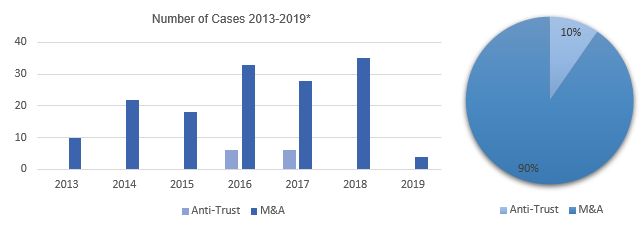

Comesa Competition Commission has handled almost two hundred (200) mergers since inception, granting most unconditionally, some conditionally and declining or withdrawing a few. Three important trends worth noting in 2018/19 M&A include the following:

- Petroleum (Oil & Gas), Construction (Real estate & Infrastructure) and ICT, are target sectors,

- Multinational corporations dominate the investment space against indigenous firms,

- Conditions in acceptance generally focus on regulating injustices.

Statistics have shown that the Commission has only investigated and decided upon very few anti-trust and consumer protection matters. One of the most important cases that shows the impact of competition regulation on cross-border businesses in the Common Market is the case concerning the Allegations of Misleading Adverts by Fastjet Airlines Limited (the "Fastjet case"). It is locus classicus because it covers both anti-trust and consumer protection.

Fastjet is a predominantly British owned pan-African low-cost carrier that only operates in Africa. It is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is the brainchild of former Easyjet and Go (British Airways) founders. Fastjet operates in East, West and Southern Africa under the brand names, "Fastjet" and "Fly540", with offices in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, Harare, Zimbabwe and Johannesburg, South Africa. Southern African operations are predominantly African owned.

The brief background of the matter is that allegations of "misleading advertising" were levelled against Fastjet's Tanzanian office ("Fastjet Tanzania") for its marketing in Kenya.1 It is Fastjet's general marketing policy that it advertises its tickets excluding tax and related government charges. The Competition Commission made its initial investigations on the 23rd May 2016, and determined that Fastjet's advertising in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe ("Fastjet Group") was in violation of Comesa Competition Regulations.

The CID relied on Article 27(g) of the Regulations which provides as follows:

"A person shall not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services"

Fastjet Kenya complied with the said regulations by ceasing the advertising model in consultation with the Kenyan Civil Aviation Authority. The standing position is that Comesa issued a formal warning to all Member States where Fastjet operates effective from 12th July 2016, to abstain from continued use of this advertising model.2 This means that formal communication reached both the competition commissions and civil aviation regulators of all the Member States for enforcement, not only where the Fastjet Group operates. Fastjet escaped a fine, however, it is under close scrutiny by authorities within the Common Market and its competitors would relish an opportunity to raise the alarm should any further violations occur.

There seems to be sufficient authority within the regional and global airline industry at large to support the CID's strictness, if one considers similar sanctions against Rynair in 2005 and British Airways in 2014. In 2011, South African Airways ("SAA") and ticket agent Destination Southern Africa were fined US$75,000 for 'deceptive price' advertising by the U.S. Department of Transportation ("DOT"). SAA, unlike Fastjet was actually confusing its customers because when consumers clicked on a link next to the fare listed on the homepage, they were taken to a second page where they could select a specific vacation package. Only after selecting, were they taken to a third page where they could see the taxes, fees and the requirement for double occupancy. This violated the DOT policy which requires internet fare listings to disclose separate taxes and fees through a prominent link next to the fare stating that government taxes and fees are extra, and that the link must take the viewer directly to information where the type and amount of taxes and fees are displayed.3

Fastjet, in their defence argued that their advertising policy was clear enough as it not only explained the fare in detail below the advert but actually redirected the customer to the direct booking page with the full fare. The defendant did not appeal this decision to the Board of Commissioners. The prospects seemed minimal even at domestic level. Competition rules surrounding allegations of deceptive advertising are very strict in most jurisdictions because the rationale is not only to level the playing field in the industry but to protect unsuspecting consumers. In the Member State Zimbabwe for instance, "Misleading advertising" is a strict liability offence because it is a form of "public welfare offence" that is, an offence involving prohibitions or duties designed to protect the general public.4

Prosecution need not prove a mental element such as intention or negligence for determining the actual commission of the crime.5 It is therefore not necessary to show that the service provider intended to deceive the consumer, but only that the consumer was misled or deceived by the advertisement. This means that an accused cannot rely on the same defences available where intention or negligence is a requirement.

It is my considered view that the Commission erred in its finding. Competition law in many jurisdictions within the Common Market, recognises genuine bargains as a legitimate marketing strategy. This is especially appropriate for a low-cost carrier, such as Fastjet that offers the so called "budget" travel packages. The adverts are not "misleading" or "false", as they are clear in prescribing the airline's bargain price as well as the provision for additional taxes which any reasonable customer ought to understand. There is absolutely no deliberate attempt to hide the complete air fare as the customer has all the necessary information to make an informed decision.

The effect of such a ruling for a low-cost carrier, is quite significant. Affordability is what a low-cost carrier sells, especially a pan-African one such as Fastjet that is trying to break into a lucrative market. Africa, which holds about 15% of the planet's population and 20% of earth's land mass, only benefits from less than 3% of the world's aviation sector.6 Fares charged by operators in Africa are often four (4) times the cost ("seat per kilometre basis") of those charged in other regions like Europe, for instance.7

Practical considerations for your client

The forum

Institutional structure may be summarised as follows:

|

Comesa Court of Justice: |

Has jurisdiction over all matters within the Comesa Treaty, as a court of first instance and advisory body for the Council and Member States. It has been operational since 2000 in Khartoum, Sudan. It acts as appellate court for competition matters. |

|

Board of Commissioners: |

Handles all appeals from the Competition Commission. It is the supreme policy organ of the Commission. |

|

Competition Commission's CID: |

The Committee for Initial Determination conducts all investigations and makes preliminary decisions on all matters brought before the Commission. |

The law

Anti-trust and merger cases are governed by the Comesa Competition Regulations, Competition Rules, 2004 as amended in 2015 together with guidelines for Competition and Merger Assessment. According to the Treaty, Comesa law is binding on all Member States and therefore takes precedence over domestic law in all competition matters, therefore parties cannot have recourse to domestic legislation on Comesa matters. Jurisdiction is triggered once the following has been determined:

- Cross-border application,

- Threshold.

In M&A, the Regulations apply where both the acquiring firm and the target firm or either operates in two (2) or more Member States. The jurisdictional limit therefore is that there should be some minimum level of cross-border activity. Take note that a firm need not be domiciled in a jurisdiction to qualify for extra-territorial application, so long as it conducts business through exports, imports, distribution channels and subsidiaries.

In addition, once the mergers have been deemed applicable in Comesa, the regulations create a mandatory notification system detailed below. A notifiable merger must satisfy the following thresholds:

- The combined annual turnover or value of assets (whichever is higher) of the merging parties in the Common Market equals or exceeds US$50 million and,

- Each of at least two (2) of the merging parties has annual turnover or assets in the Common Market of US$10 million or more.

Now, if one was to file in a Member State such as Zimbabwe for instance, then Counsel should expect the national competition authority to apply a threshold of US$1.2 million (combined annual turnover of parties). If value exceeds US$10 million, however, then the Comesa monetary jurisdiction applies. The thresholds would not apply where each of the merging parties generates two thirds or more of the annual turnover in one and the same Member State.

The procedure

The Commission should be notified within thirty (30) days of the parties' decision to merge, failure of which attracts fines of up to 10% of either one or both merging parties' turnover in the Common Market. The law is actively enforced within the Common Market and investors within the various Member States comply. In terms of timelines, Counsel should expect a decision within four (4) months or one hundred and twenty (120) calendar days for a complex merger (phase 2) and forty-five (45) calendar days for a phase 1. Aggrieved parties may appeal to the Board of Commissioners in terms of the Regulations. Further appeal lies with the Comesa Court in Khartoum. The procedure is covered in the Rules of the Court. The Court's decision is final and not appealable at national level. In fact, the Court's rulings take precedence over those of the national courts of Member States and Member States may quote precedents from its rulings. Whilst the Court has a mandate to make rulings on any issue related to the interpretation of the Treaty, Counsel should take note that the Commission may be a faster route for issues of clarity.

Comesa Competition has created a "one-stop-shop", hence merger notification at the regional office eliminates multiple filing in each of the competition authorities within the Common Market. Caution, however, is advised as there are certain Member States like Kenya that are yet to regularise their operations in line with the Treaty, hence it is advisable to confirm with the national competition authority if a local notification is still mandatory.

The cost

Filing fees have been reduced. They were previously set at 0.5% of parties' combined turnover or assets (whichever is higher) up to a maximum of up to US$500,000. The new fees are set at 0.1% of combined annual turnover or assets (whichever is higher) up to a maximum of up to US$200,000. The only way to avoid the regional fees altogether is to attempt a national notification. Comesa Competition Rules apply to mergers that have "an appreciable effect on trade between Member States and which restrict competition in the common market." The 2015 Guidelines clarify that where there is minimal effect on the local market, then there is no need for regional notification. Counsel must apply to the Commission within thirty (30) days of decision to merge, to be issued with a "Comfort Letter" to enable national notification and avoid the high regional filing fees. Counsel must expect the Comfort Letter within twenty-one (21) days, subject to any additional clarification or documentation. If Counsel was required to file national notification for a transaction in Egypt, Kenya and Zimbabwe for instance, then they should expect fees within the following ranges: Egypt (US$0), Kenya (min US$10,000-max US$100,000) and Zimbabwe (min US$10,000 - max US$50,000). Regional filing still appears higher.

Concluding remarks

The Commission has come a long way in the provision of clarity, certainty and predictability of the enforcement system. This value proposition is still an ongoing concern; clearly, however, a business case still exists for a regional competition regime. Abuse of dominance is one of the major barriers to fair trade and a big obstacle for indigenous firms. A dominant position is defined by Article 17 of the Regulations as "an ability to influence unilaterally, price or output in the Common Market or any part of it". This is when a company occupies such a powerful economic position that it dictates the terms of business for a certain sector in the Common Market. Comesa needs to step up its investigation and prosecution of cartels in the Common Market.

Comesa Competition control is doing relatively well with what it has, against its counterpart, the EU. Resources are limited, however; Members States have different levels of development and there is need for more buy-in from Member States to raise its standards to a comparable one-stop-shop facility. Counsel is therefore advised to always check the extant procedural arrangement between Comesa and the respective Member States before instituting notification proceedings.

FootnoteS

1 Decision of the Twenty Third Meeting of the Committee Responsible for Initial Determination Regarding the Allegations of Misleading Adverts by Fastjet Airlines Limited Staff Paper No. 2016/06/JB/08

2 In terms of Article 24 (6), Regulations, the Commission takes the "behaviour" of the parties into consideration

3 https://www.consumeraffairs.com/airline-advertising-rule-violations

4 See Competition Act of Zimbabwe and the classical case of S v Maceys of Salisbury Ltd 1982 (2) ZLR 239 (S) (statute on contamination of foodstuffs) and Zimbabwe United Freight Co Ltd 1990 (1) ZLR 357 (S)

5 Section 17 (1) Criminal Law (Codification & Reform) Act of Zimbabwe 9:23

6 According to the International Air Transport Association ("IATA"), rapid population growth in Asia and Africa is amongst the top drivers of change; "The future of the airline industry 2035", IATA (2017), 6.

7 IATA

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.