Multilateral development banks spend $70bn each year on loans and grants to the developing world. In April 2010, for example, the World Bank approved a $3.75bn loan to South Africa-based Eskom Holdings, to build one of the world's largest and most complex power plants. This was just one of the nearly 30,000 contracts the Bank awards annually. Despite the worldwide recession, the World Bank's member countries recently approved a $5.1bn capital infusion to spur more lending. Together, development banks' largesse is spread over thousands of contractors, which range from small local construction firms to major multinational corporations.

The development banks now look harder at allegations of corruption, fraud and other misconduct in bidding and contracting. Collectively, they have debarred more than 1,100 firms and individuals from contract eligibility in the past decade. In recent years, the banks have cooperated to revise and implement new procedures that will improve their effectiveness in detecting, investigating, sanctioning and deterring misconduct. The banks have also raised the penalties for violations of their rules, which now include worldwide debarment and referral for criminal prosecution.

Today, contractors thus find themselves more likely to face long and costly investigations by the banks, which hold the purse strings and can ban them from bidding on new jobs. Companies doing business with the World Bank or other multilateral development banks should prepare to be investigated by the banks' integrity groups in response to whistleblower complaints or other allegations. They should also make sure their compliance programs are up to date, both to avoid violations and to provide a defense if they happen in spite of reasonable precautions. If a contractor discovers evidence of misconduct, it should consider whether to tell the bank about it under a voluntary disclosure program. That may well be a difficult decision.

"Internationalization of punishment"

In April 2010, the World Bank vice-president for institutional integrity, Leonard McCarthy, announced an agreement by the five largest development banks to "cross-debar" companies that engage in fraud or corruption in connection with projects financed by the banks. Mr. McCarthy, a former prosecutor, predicted that the agreement would lead to an "internationalization of punishment" for contractors. Under the agreement, a contractor debarred for more than one year by one of the five banks will be frozen out of bidding on projects by all of them (unless doing so "would be inconsistent with [a bank's] legal or other institutional considerations").

The Agreement for Mutual Enforcement of Debarment Decisions affects companies dealing with any of the following banks:

- African Development Bank;

- Asian Development Bank;

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

- Inter-American Development Bank Group; and

- World Bank Group.

Together, these banks account for the lion's share of the $70bn in annual financing to the developing world.

The cross-debarment agreement follows a 2006 accord among the banks that included uniform standards and procedures for corruption investigations. The World Bank and the other development banks have long had rules against corruption and fraud. For many years, those rules were honored mostly in the breach, on the theory that the banks' main mission was to help poor countries grow, not to impose the developed world's legal and moral standards on them. That has changed. In the past four years, the Asian Development Bank has doubled its integrity staff. Notably, the banks have recruited seasoned prosecutors. Additionally, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank now track allegations and investigations with sophisticated computer programs. The 2006 accord also led to incentives for whistleblowers to come forward with allegations and procedures to protect them from retaliation.

Many of the development banks have also created incentives for contractors to self-report violations. For example, the World Bank launched its voluntary disclosure program in 2006. The program provides for leniency, but imposes onerous obligations on contractors and severe punishment for repeat offenders. Although the World Bank has reported that several companies have applied for the program, it is far from clear whether the benefits would outweigh the costs in any particular case. In June 2010, the director of operations at the World Bank's integrity vice presidency, Stephen S. Zimmermann, announced efforts to roll out stronger disclosure incentives by the end of the year. "The World Bank is trying to create incentives for companies to come forward, and trying to be more aggressive in resolving cases," he said. Zimmermann is a former US federal prosecutor and former chief of the office of institutional integrity for the Inter-American Development Bank.

The development banks were inspired by the success of national authorities in cross-border corruption investigations under laws such as the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) as well as the similar rules across member states of the EU and other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. Indeed, the US Justice Department helped the World Bank set up its anti-corruption enforcement program. The banks' efforts also follow new stricter regimes such as the UK Bribery Act 2010.

Companies investigated by national authorities in multi-jurisdictional bribery cases have suffered endless investigations and catastrophic legal costs. The multilateral development banks now have a seat at the global anticorruption enforcement table. For bank contractors, that means more investigations and the threat of even greater sanctions.

Sanctionable conduct that goes beyond corruption

In molding a new enforcement regime, the banks have mirrored several domestic law statutes, such as the FCPA, the US False Claims Act and obstruction of justice statutes. The banks have agreed on four core sanctionable practices:

- a corrupt practice is offering, giving, receiving or soliciting, directly or indirectly, anything of value to influence improperly the actions of another party;

- a fraudulent practice is any act or omission, including a misrepresentation, that knowingly or recklessly misleads, or attempts to mislead, a party to obtain a financial or other benefit or to avoid an obligation;

- a coercive practice is impairing or harming, or threatening to impair or harm, directly or indirectly, any party or the property of the party to influence improperly the actions of a party; and

- a collusive practice is an arrangement between two or more parties designed to achieve an improper purpose, including to influence improperly the actions of another party.

Additionally, the Asian Development Bank includes conflict of interest in its anticorruption policy. The World Bank subjects obstructive practices to sanctions

A cautionary tale

In the past year, sanctions investigations have made examples of household-name contractors. For example, in May 2010, the World Bank announced that it had debarred UK-based Macmillan (one of the world's largest publishers) for six years after the company admitted paying bribes in southern Sudan – for a bid on a project that it did not even win. This case offers a useful example of the changed atmosphere for contractors.

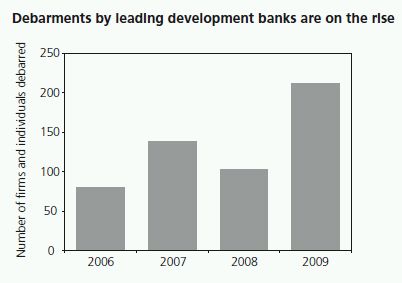

The Macmillan debarment is part of a surge in sanctions measures by the banks. In the World Bank's combined 2007 and 2008 fiscal years, for example, it debarred only two companies. In the past two years, it has debarred nearly 60 firms and individuals. In the same time, the Inter-American Development Bank has doubled its number of debarments, while the Asian Development Bank also has increased its debarments (see chart).

The banks typically require settling companies to adopt elaborate – and costly – compliance and monitoring programs to regain eligibility, which then raise the bar for other companies. In Macmillan's case, its debarment may be reduced from six years to three years if it implements a stringent compliance program and cooperates with the World Bank. Efforts to regain eligibility for bank projects mirror what is known as "self-cleansing" in government procurement. In this new area of work, we have been advising on whether self-cleansing can constitute a defense to debarment from public procurement for misconduct.>

We are considering how those cases, brought by national authorities, may benefit contractors facing a development bank investigation.

The banks are also raising the costs for errant contractors by pushing national authorities to prosecute them. The World Bank has made more than 90 referrals to domestic prosecutors, including nine in fiscal year 2009 alone, and has made a point of urging national governments to follow those referrals up with criminal prosecutions. The World Bank has also signed cooperation agreements with the UK Serious Fraud Office (SFO) and the European Anti- Fraud Office, which provide for information sharing and cooperation in enforcement proceedings. Media reports indicate the SFO has been investigating Macmillan, though it is not clear whether as a result of a World Bank referral.

Planning for sanctions investigations

Companies that receive funding from multilateral development banks should plan ahead for sanctions investigations. We suggest that internal counsel familiarize themselves with the Uniform Framework for Preventing and Combating Fraud and Corruption, which was adopted by the leading development banks in 2006, and with the particular rules of the banks with which they do the most business. The Uniform Framework and the individual banks' rules are modeled on domestic laws against bribery, fraud and other misconduct, but there is little precedent or other guidance on how the rules are enforced, because the proceedings are opaque. (The World Bank is reportedly considering publishing sanctions decisions and other transparency measures.) Sanctions investigations can involve unusual legal issues because of the banks' status as international organizations with broad immunity from domestic process. As the banks enforce their rules more aggressively, we are developing legal theories to challenge their actions in domestic courts.

Companies should review their compliance programs carefully. In a sanctions investigation, the bank will scrutinize codes of conduct, policies and procedures, and training efforts. Even after an investigation starts, it may be in the company's interest to adopt new compliance measures, rather than wait for them to be imposed by the bank. If a company learns of a violation of bank rules, it must consider whether to conduct an internal investigation and whether to disclose the violation voluntarily to the bank. These are important and difficult decisions, which should be made after a careful assessment of the facts and circumstances.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.