Last weekend, for all intents and purposes, was a quiet weekend in the middle of August; Parliament was in recess and most healthcare commentators were taking the opportunity to enjoy a well-earned summer break, and then the media airways began buzzing with a new healthcare spat, this time between the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, and Professor Stephen Hawking. The exchange saw claims and counter-claims scattered across Twitter and the pages of the weekend papers, with each contender accusing the other of ignoring evidence.1 For me, while the need for evidence based policy is undoubtedly important, at the heart of the debate is the question of funding and whether the government's plans for the NHS, espoused in the Five Year Forward View2, are achievable within the current funding envelope? I've therefore used this week's blog to explore what's been happening to NHS funding.

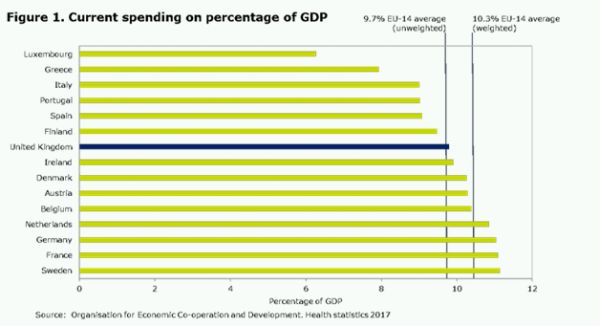

My current interest in the question of funding was sparked by John Appleby, of the Nuffield Trust, publishing his analysis of changes in the OECD's assessment of international spending on healthcare which challenges the perceived wisdom of the past 17 or so years. The traditional view, which I have personally ascribed to, is that the UK is spending less of its national income on healthcare than other comparative European countries, and that if it wishes to have a first class service it needs to spend at least as much as the average spend of 9.7 per cent (in 2014). Indeed, the previous OECD figures supporting this view suggested that the 8.6 per cent of UK GDP spent on healthcare lagged behind that of countries such as Greece, Italy and Slovenia. Moreover, that in providing the NHS with less than one per cent, year-on-year funding increases over the past six or so years, the UK has seen its position fall back to the same level as it was in 2000.

However, the OECD recalibration, suggests that we actually spent about 9.8 per cent of GDP on healthcare (including both the NHS and private health) in 2014; slightly above the average of 9.7 per cent for the EU 15 (the member states before the new joiners in 2004). This new definition of spending on 'health' (at least for the purposes of international comparisons) now includes more of what we in the UK have traditionally thought of as 'social care' spending, as well as NHS spending on preventative care.3

Even if this is a fairer comparison, there remains quite a difference between UK spending of 9.8 per cent and the 11.1 per cent being spent by France, Germany and Sweden. In cash terms, the difference is about £24 billion a year.4 Moreover, as demonstrated in other research, NHS providers are struggling to break even, there are not enough staff, social care is in crisis, and the increase in demand for health and social service is unrelenting. As a result, knowing where we stand in comparison to spending in other countries (see figure 1) feels meaningless.

As we argue in our report, ' Vital Signs: How to deliver better healthcare across Europe', all countries in Europe are facing similar challenges - unrelenting demand pressures, growing public expectations, a mismatch between demand and supply of healthcare staff, and increasing costs driven by new technology and advances in medical equipment and pharmaceutical interventions. What differs is the approach adopted by each country, what they are prepared to pay for and what they are prepared to trade off or prioritise. How much we actually spend on health is determined by history, culture and the economic and political environment in which the health service operates. However, how much we should spend on health care is still a live and important debate, but the argument that we should spend more simply because we spend less than the rest of Europe is no longer enough, nor should it ever have been.

Some commentators argue, and indeed there is some evidence to back up the argument, that the UK is the fairest and most-cost effective system in the world.5 While the NHS does indeed do well on a number of measures including efficiency, affordability, equity and some aspects of the process of care, it continues to perform poorly in terms of outcomes such as infant mortality, the number of adults with two or more chronic conditions, and amenable mortality (i.e. mortality from a range of conditions in the under 75s which can be reduced by effective health care, such as five-year survival for breast and colorectal cancer).

However, it is hard to argue against the evidence that our cancer survival rates and other health outcomes remain poor compared to many other developed countries in Europe. Indeed, data from the Global Disease Burden Study which examines healthcare access and quality based on mortality from causes of amenable to health, also places the UK well behind most of Western Europe (although again, ahead of the USA) when measuring avoidable deaths.6

One almost unique feature of the UK is the impact of successive Government's influence on health particularly in England, which has led to more reorganisation and restructuring than any health system in Europe. A second is the reliance on regulation, inspection and performance management which seems to be much more pronounced in the NHS than in most other health systems.7

The Next Steps for the NHS Five Year Forward view published in March 2017, acknowledges that new treatments for a growing and aging population mean that pressures on the service are greater than they have ever been. It also identifies areas where treatment outcomes have improved and identifies an ambitious and stretching NHS 10 Year Efficiency plan. It contains laudable and stretching targets, supported by targeted funding, to deliver a better, more joined-up and more responsive NHS in England.8

At the same time, the latest analysis from the Kings Fund quarterly monitoring review of NHS finance directors, suggests that NHS finances improved over the last quarter of 2016/17, with more than half of finance directors (54 per cent) expecting to have ended the year in surplus. However, much of this was down to one-off actions such as selling land. However, high levels of concern remain about the risk of NHS providers running up a significant deficit in 2017/18.9

Our own research suggests that the NHS has little choice but to increase spending if it is to tackle the irrefutable evidence of lengthening hospital waiting times, addressing the difficulties patients face in getting GP appointments, tackling the maintenance backlog, investing in technology and IT infrastructure and, most of all, improving the recruitment and retention of nursing and medical staff.

The two positions of ambition and the reality of performance suggest there is a gap of what policy makers want to happen and what is happening on the front line. Having recently interviewed a number of NHS leaders working on front line services their 'stay awake' issues are first and foremost workforce, and then whether they have enough funding to implement the much needed IT and technology transformation required, despite their being support for the ambition of the Five Year Foreword View. For me, the missing ingredient is that there has to be some additional funding and this needs to be equitably spread. Moreover, the implementation of any new initiative has to be based on evidence based practice and transparency, or there is a risk of seeing more 'spats' between eminent public figures arguing about what is really happening in the NHS.

Footnotes

1 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-40967309

2 https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-five-year-forward-view/

3 https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/spending-on-health-how-does-the-uk-compare-internationally

4 https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/spending-on-health-how-does-the-uk-compare-internationally

5 http://www.commonwealthfund.org/interactives/2017/july/mirror-mirror/

6 http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)30818-8/fulltext?elsca1=tlpr

7 www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/the-fairest-of-them-all-examining-the-nhs-s-global-ranking

8 https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/next-steps-on-the-nhs-five-year-forward-view/

9 http://qmr.kingsfund.org.uk/2017/23/overview

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.