In its first collision case, the UK Supreme Court overturned a Court of Appeal and Admiralty Court judgment involving collision outside a narrow channel, affirming the crossing rules did apply and were engaged. Cyprus and her ships are bound by these rules, and this scenario may feature outside ports with narrow entrances.

At its heart, Evergreen Marine (UK) Limited v Nautical Challenge Ltd is a collision case involving a vessel ('the Ever Smart') leaving a narrow channel, and another vessel ('Alexandra 1') ultimately intending to enter it. A narrow channel may include an appropriately narrow harbour entrance, therefore the application potential is significant and similar facts may reoccur.

The case juxtaposes two sets of rules within the 1972 IMO Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea ('COLREGs'), namely the specialised narrow channel rule (Rule 9), and the more widely applied crossing rules (Rules 15-17). Cyprus is a signatory to the COLREGs, therefore the same rules apply to Cyprus registered ships and to foreign ships within her territorial waters. This case could therefore be viewed as a relevant authority by Cypriot courts.

The case asks whether only one or both sets of rules apply outside narrow channels, and if both apply, which set prevails. Under Rule 9, vessels ought to keep to starboard. Under Rule 15, the vessel that has the other vessel to its starboard side gives way. For reasons that shall become apparent, the two sets may lead to opposing conclusions and collision, so it is important for mariners to be clear which rules come on top, and under what specific circumstances. It is therefore arguably unsurprising the case reached the UK Supreme Court, in fact constituting its first collision case since its inception, nearly 50 years since a collision action last came before its predecessor the House of Lords. In spectacular fashion, the Supreme Court overturned the Court of Appeal and Admiralty Court judgments in February, deciding the crossing rules did in fact apply and moreover were engaged. In accordance with Rule 15 thus, Alexandra 1 had Ever Smart to starboard, and had to give way.

The facts

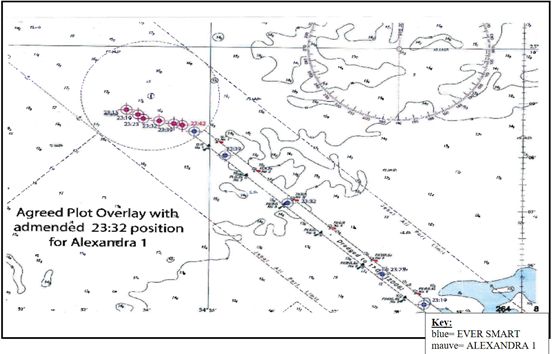

The Ever Smart (a large container vessel) and the Alexandra 1 (a very large crude carrier or VLCC) collided at night, within the pilot boarding area outside the dredged entrance/exit channel to the port of Jebel Ali in the United Arab Emirates ('UAE'). The Ever Smart was proceeding along the channel mid to port about to exit it, while Alexandra 1 was waiting (but was not stationary) to embark a pilot released from the Ever Smart before entering. The Master of Alexandra 1 crucially misattributed a conversation between Port Control and a tug believing the former was addressing the Ever Smart, and that the latter would pass 1 mile astern of Alexandra 1. He did not therefore prepare to enter to starboard, in compliance with Rule 9. Meanwhile, the Ever Smart had disembarked the pilot, and was proceeding at full speed ahead on the wrong side (port side) of the channel under Rule 9. The collision resulted in a $32 million damage for Alexandra 1, and a $4 million damage for the Ever Smart.

Admiralty Court and Court of Appeal

Tear J of the Admiralty Court sat together with Nautical Assessors of the Elder Brethren of Trinity House, and relied on what he considered as 'statements of principle' laid out in the Canberra Star1 and Kulemesin2. The passages he quoted were to the effect that the approaching vessel should navigate to a starboard approach of the channel, the vessels not bound by the crossing rules. Arguing two sets of rules with different requirements applying at the same time would cause confusion and jeopardise safety, he concluded "the crossing rules cannot have been intended to apply where one vessel is navigating along a narrow channel and another vessel is navigating towards that channel with a view to entering it". Tear J also accepted Alexandra 1's submission that she was not "on a sufficiently defined course for the crossing rules to apply". The Admiralty Court decided the faults of the Ever Smart were far greater both in terms of relative culpability and causative potency, holding Alexandra 1 responsible only for failing to keep a good aural lookout (i.e. misattributing the Port Control discussion). The Ever Smart was held 80% liable.

The Court of Appeal also sat with Elder Brethren of Trinity House and stress-tested the Admiralty Court's findings on the disapplication of the crossing rules via a hypothetical opposite (East to West) approach scenario. This hypothetical scenario was cleverly raised by the Ever Smart, to support the crossing rules had to apply in that case, otherwise there would be no rule of priority. The exiting vessel would be keeping to starboard (complying with Rule 9) and the vessel about to enter would have to cross to get to its starboard side of the channel and comply with the same rule. The Court of Appeal was satisfied with advice received by the Elder Brethren on prudent mariners' actions the vessels would take in that case to mitigate collision risk (such as keeping a sharp lookout, consulting Port Control and maintaining radar monitor) and upheld the Admiralty Court's judgment on liability, and its finding the crossing rules did not apply.

The case returned to the High Court for damages to be assessed, and interesting issues were raised in terms of extended loss, which factored in underwriters' refusal to pay Alexandra 1 owing to illegal Iranian trade, her owner's impecuniosity and inability to pay for repairs, as well as a question of permanent diminution in value. These issues however were not considered by the Supreme Court, and consequently are not reviewed here.

The Supreme Court judgment

The Supreme Court's 5-judge panel once again sat with Elder Brethren of Trinity House, to address two questions: 1) whether the crossing rules were inapplicable or should be disapplied, and 2) whether their engagement depended on the approaching vessel being on a steady course. The judgment is characterised by a down-to-earth common sense approach to the COLREGs, and contains what ought to become classic passages on the interplay between the individual rules.

The Supreme Court distinguished 3 different groups of vessels depending on the nature of their activity in areas just outside the entrance to a narrow channel. Group 1 featured vessels which were simply heading across the channel, not intending to enter. It was common ground between appellants and respondents that the crossing rules applied between an exiting vessel, and a Group 1 vessel. Group 2 featured vessels intending to enter on their final approach to starboard towards the channel, adjusting their course accordingly. It was also common ground that the narrow channel rule applied here, and the crossing rules did not.

Group 3 contained approaching vessels waiting to enter, rather than entering, and was in dispute. The Supreme Court considered Alexandra 1 to be in Group 3, and decided that for a Group 3 vessel the crossing rules were not overridden, until the vessel was shaping to enter and adjusting its course accordingly (in other words became a Group 2 vessel). The authorities relied on by The Court of Appeal and Admiralty Court were effectively Group 2 authorities. Moreover, the Supreme Court disagreed with the Court of Appeal's conclusion that the good seamanship advice received by the Elder Brethren to mitigate collision risk was sufficient to support disapplication of the crossing rules, as in that scenario this meant the risk of collision was not addressed by any rule.

On the steady course requirement, the Supreme Court distinguished between heading, course and bearing. Heading was construed as the direction in which the vessel was pointing, course as the direction in which a vessel was moving, while bearing as the direction in which one vessel appeared when viewed from another vessel, all measured in degrees in a compass. The Supreme Court decided it was the bearing and not the course or direction that was crucial to the engagement of the crossing rules. Given the vessels were on a constant bearing for 23 minutes prior to collision, their relative changes in course and speed cancelling each other out, the crossing rules were engaged.

The case now returns to the Admiralty Court for reapportionment of liability.

Concluding remarks

The Supreme Court's judgment in Evergreen Marine (UK) Limited v Nautical Challenge Ltd constitutes a tour de force of legal analysis on collisions, and should be studied in detail by Admiralty practitioners. It reinforces the central role of the COLREGs, which are not to be substituted by good seamanship alone, and stresses the requirement to investigate the precise factual pattern of a collision, before extrapolating from past legal authority. Moreover, there is an underlying message that in collisions, where technicality clashes with common sense, the latter shall prevail. The case should constitute persuasive authority in Cypriot courts, given its prominence within the UK Supreme Court.

Footnotes

1 The Canberra Star [1962] 1 Lloyd's Rep 24

2 Kulemesin v HKSAR[2013] 16 HKCFA 195

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.