MAJOR MARKET COMPARISON OF KEY COVID-19 LEGISLATION

As pharmaceutical companies worldwide race to supply vaccines and therapeutics to fight the spread of COVID-19, understanding the laws and regulations that could impact parties involved in the COVID-19 pandemic supply chain is increasingly important. This article provides an overview and comparison of legislation relevant to manufacturers, suppliers, distributors, and health professionals involved in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic in each of the United States ("US"), European Union ("EU"), United Kingdom ("UK"), and People's Republic of China ("PRC"), including measures to ensure (1) immunity from COVID-19 countermeasure liability; (2) government ability to direct (or redirect) resources; (3) emergency use authorizations; (4) price-gouging prevention; (5) cooperation between companies; and (6) export controls.

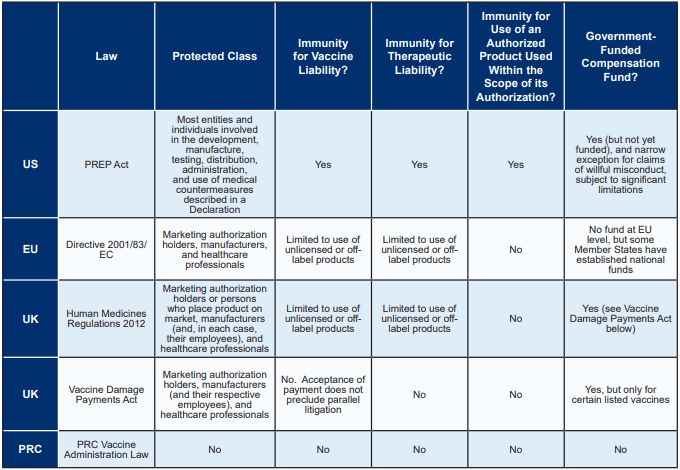

IMMUNITY FROM COVID-19 VACCINE AND THERAPEUTIC LIABILITY

The United States has the most comprehensive pandemic product liability protection legislation of the major markets, affording broad immunity to actors involved in the COVID-19 supply chain for both vaccines and therapeutics. While the EU and UK provide limited immunity for the use of unlicensed or off-label medicinal products, the PRC does not provide any immunity for vaccine or therapeutic liability. The following table compares immunity from COVID-19-related liability in each of the major markets, as further described below.

United States

The US Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act ("PREP Act")

Enacted in 2005, the PREP Act authorizes the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services ("HHS") to declare a public health emergency identifying "covered countermeasures" and providing immunity against claims of loss arising from such covered countermeasures. A PREP Act declaration was issued on March 17, 2020, retroactive to the initial emergency declaration on February 4, 2020, for activities related to "Covered Countermeasures" against COVID-19, including COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, medical devices, and diagnostics, which has since been amended several times.1 In general, such "Covered Countermeasures" are approved, cleared, or licensed by the US Food and Drug administration ("FDA"); authorized under an Emergency Use Authorization by the FDA; authorized for investigational use, i.e., under an Investigational New Drug ("IND") or Investigational Device Exemption ("IDE"); or otherwise permitted to be held or used for emergency use in accordance with US Federal law.

The PREP Act, when invoked in a declaration under a pending emergency, provides immunity for the manufacture, testing, development, distribution, administration, and use of such covered countermeasures against chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear agents of terrorism, epidemics, and pandemics-including COVID-19. Individuals who suffer injuries from the administration or use of products covered by the PREP Act's immunity provisions may seek redress from the Countermeasures Injury Compensation Program ("CICP"), which is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (part of the HHS). The CICP is a "payer of last resort," and any benefits from the fund are reduced by the amounts payable by all other public and private third-party payers (such as health insurance and workers' compensation).

Immunity protections are broad, and contrary state and local laws and rulings are widely preempted; practically, the only time a manufacturer of a COVID-19 covered countermeasure would not benefit from PREP Act immunity would be if a suit is brought in the US District Court for the District of Columbia by a plaintiff who has suffered a serious injury or death, has rejected a payment from the fund (which is not currently funded for COVID-19-related claims), and has demonstrated by clear and convincing evidence that the manufacturer engaged in "willful misconduct," as defined in the statute. It is worth noting that enforcement actions against manufacturers of covered countermeasures regulated under the Public Health Service Act or the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act are not considered willful misconduct unless the government initiates an enforcement action that actually results in a criminal, civil, or administrative penalty.

Unsurprisingly, the PREP Act does not provide immunity for foreign claims where the US lacks jurisdiction. However, immunity may be available for administration or use of a covered countermeasure outside the US if the claim is based on events that take place in the US or another link to the US makes it reasonable to apply US law.

European Union

Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use, as amended ("Directive 2001/83/EC")

Directive 2001/83/EC was enacted in 2001 to consolidate earlier EU legislation relating to medicinal products for human use and remains the primary legislation governing the regulation of pharmaceuticals in the EU. Directive 2001/83/EC and other EU directives are transposed into the national laws of the EU Member States and are implemented, applied, interpreted, and enforced by their national competent authorities and courts as well as by the European Court of Justice.

Like the PREP Act, Directive 2001/83/EC broadly applies to all "medicinal products." However, the scope of the immunity afforded to persons involved in the COVID-19 supply chain is more narrow than the PREP Act. Article 5(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC requires Member States to put in place provisions to protect marketing authorization holders, manufacturers, and healthcare professionals from civil or administrative liability for any consequences from the use of (1) an unauthorized medicinal product or (2) the off-label use of an authorized medicinal product, if such use was required or recommended by a competent authority in an EU Member State in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The scope of such protection may vary between Member States depending on the wording of national laws implementing Article 5(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC. There is no pan-EU compensation fund available with respect to injuries experienced following receipt of a vaccine or COVID-19; however, some individual EU Member States have established funds that are available to their citizens at the national level.

Furthermore, Article 5(4) of Directive 2001/83/EC states that the limitation of liability provided under Article 5(3) does not affect the manufacturer's liability for defective products set out in Directive 85/374/EEC (also known as the "Product Liability Directive"). A medicinal product is considered to be defective if it does not "provide the safety which a person is entitled to expect, taking all circumstances into account." This is likely to apply, for example, in cases of quality issues in the manufacturing of the medicinal product. Liability under the Product Liability Directive is subject to a number of defenses, including the so-called "development risks defense," which provides that a producer is not liable if it can establish "that the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the time when he put the product into circulation was not such as to enable the existence of the defect to be discovered."

While governments in the EU have been resistant to any general immunity for producers of medicinal products, including those developed in a pandemic, the application of the Product Liability Directive is likely to mitigate at least to some extent the risk of a finding of liability. Therefore, the circumstances to be taken into account when assessing a "defect" include whether a product had been developed under accelerated timelines in a pandemic situation (including potentially the fact that a marketing authorization was granted on a conditional basis), in which case the development risks defense is likely to apply. However, the defenses available under the Product Liability Directive do not protect producers against the resource and cost implications of litigation.

United Kingdom

The Human Medicines Regulations 2012,2 as amended ("Human Medicines Regulations" or the "Regulations")

The Human Medicines Regulations, established in 2012, consolidated UK legislation relating to medicinal products for human use in certain areas, including manufacturing, wholesale dealing, and marketing authorizations. Regulation 345 of the Regulations (which implements Article 5(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC in the UK) protects marketing authorization holders or those responsible for placing the product on the market, manufacturers (and their respective employees), and healthcare professionals from civil liability for loss and damage resulting from the use of an unauthorized or off-label medicinal product if such use was required or recommended by the UK licensing authority in response to the suspected or confirmed spread of pathogenic agents, toxins, chemical agents, or nuclear radiation that may cause harm to human beings-including COVID-19.

The Human Medicines Regulations were most recently amended on October 16, 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic to, among other things, expand the immunity from civil liability afforded to healthcare workers and manufacturers to also include companies producing the vaccine. Unlike the PREP Act, the Human Medicines Regulations do not provide immunity for use of an authorized product used within the scope of its authorization.

Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979 (the "Vaccine Damage Payments Act" or the "Act")

Under the Vaccine Damage Payments Act, the UK Government provides a lump sum payment (currently £120,000) to individuals severely disabled (defined as at least 60% disability) as a result of vaccination against certain diseases listed in the Act. The Act was initially enacted in response to children who had become severely disabled from the whooping cough (pertussis) vaccine. The list of diseases to which the Act applies is regularly updated by statutory instrument, most recently to include COVID-19. Entitlement to payment under the Act is generally limited to individuals vaccinated before their 18th birthday or who received a vaccine at the time of an outbreak of the relevant disease in the UK. However, payments following certain vaccinations, including COVID-19, are not limited in this way.3 Unlike the PREP Act, which applies broadly to vaccines and therapeutics, the Vaccine Damage Payments Act applies only to certain vaccines.

Claimants who seek compensation in excess of the £120,000 payment under the Act or who wish to claim with respect to a vaccine that is not listed must file a negligence or strict liability claim under the Consumer Protection Act 1987 ("CPA," which implements the EU Product Liability Directive 85/374/ EEC in the UK). The CPA (in line with the Product Liability Directive) imposes liability on the producer of a defective product without needing to establish fault.

Litigation brought against vaccine manufacturers has had limited success in the UK courts to date. Except in isolated cases where manufacturing defects have been established, claimants have experienced difficulty proving both defect4 and causation.5

People's Republic of China

<

The PRC does not have any legislation equivalent to the PREP Act. Although the Vaccine Administration Law was recently enacted on December 1, 2019, it does not provide, nor do other relevant laws and regulations provide, immunity for the manufacture, testing, development, distribution, administration, or use of medical countermeasures against pandemics.6 However, both public administrative systems and private tort liability play important roles in vaccine regulations in the PRC.

First, the Vaccine Administration Law imposes an administrative penalty on marketing authorization holders and manufacturers involved in various Good Manufacturing Practices, pharmacovigilance, or regulatory violations such as the production or sale of vaccines that are counterfeit or of inferior quality, use of illegal production procedures or processes, failure to established a vaccine electronic traceability system, and failure to comply with vaccine storage and transportation management regulations.

Second, the Vaccine Administration Law imposes liability for death, severe disability, and damage to organs and tissues caused by an abnormal reaction to vaccination.7 In such cases, (1) government funds are available and must be used to compensate the injured for mandatory vaccinations (e.g., Hepatitis B, poliomyelitis, Baibai Po) and (2) marketing authorization holders must compensate the injured for voluntary vaccinations (e.g., flu, HPV). At present, COVID-19 vaccines are classified as neither mandatory vaccinations nor voluntary vaccinations. Although no detailed standards or a classification process exist, mandatory vaccinations are generally proposed by the national health and finance sectors and then approved by the State Council.

For damages caused by quality issues of a vaccine, the marketing authorization holder of such vaccine must bear the liability.

GOVERNMENT'S ABILITY TO DIRECT RESOURCES

The US is the only major market with legislation permitting the government to direct or redirect US resources for national defense purposes. The EU has recently signaled a desire to implement similar legislation in response to shortfalls in COVID-19 vaccine production, while the PRC has a variety of regulations, measures, and precedents it can employ for similar purposes of product control, allocation, and prioritization.

United States

The Defense Production Act of 19508 ("DPA")

Congress first passed the DPA in September 1950 in response to the US's military unpreparedness for the Korean War. The DPA is the primary source of Presidential authority to expedite and expand the supply of materials and services from the US industrial base in order to support the national defense on a temporary basis. Over the years, the meaning of "national defense" has been expanded and now includes, among other things, emergency preparedness activities conducted pursuant to Title VI of the Stafford Act; protection or restoration of critical infrastructure; and efforts to prevent, reduce vulnerability to, minimize damage from, and recover from acts of terrorism within the US.

The DPA carries two principal authorities. The first is "rated" or "priority orders," pursuant to which the President may compel companies to accept and prioritize contracts for supplies critical to the national defense. If received, rated orders must be accepted and performed. Narrow exceptions apply where performance as ordered is not possible, but the recipient is generally required to offer the next-best substitute performance. DPA orders also flow down the recipient's supply chain such that subcontractors or suppliers must prioritize the rated order over competing obligations as well. Although performing a priority order may require breach of other contractual obligations, the DPA forecloses civil liability for damages or penalties resulting from actions taken to comply with the DPA.

The second authority is "allocation orders," pursuant to which the President may compel industry actors to allocate resources-for example, by reserving manufacturing capability or supplies in anticipation of a rated order or allocating manufacturing capability to a particular purpose. This generally requires proportional allocation across an industry; individual market participants cannot be singled out.

Failure to comply with a DPA order carries criminal penalty. Due in part to this legal risk, very few cases are litigated to test the true scope of authority. Receiving a DPA order may carry advantages for managing the supply chain and obligations to third parties, as it provides manufacturers the ability to require their subcontractors to prioritize the manufacturer's product over a competitor's product.

The Trump Administration used both authorities in response to COVID-19, primarily by issuing rated orders to compel production of critical equipment (e.g., ventilators, vaccine and testing supplies, personal protective equipment ("PPE")), as well as using allocation orders to impose very limited restrictions on exports of PPE and compel ongoing operation of critical factor operations (e.g., the food supply chain). In many cases, the Trump Administration preferred to negotiate with the private sector rather than issue formal DPA orders, but at least some of the BARDA Operation Warp Speed supply chain contracts were rated orders.

President Biden has issued an executive order authorizing the heads of the relevant government agencies to use the DPA to fill shortfalls in COVID-19 response supplies. For more detail on this, please see our advisory located on our website: https://www.arnoldporter.com/en/perspectives/ publications/2021/01/expanded-use-of-the-dpa.

Although never tested in litigation, the US government has historically adopted the position that the DPA applies only to US business operations. This is consistent with a fair reading of the statute. Accordingly, the DPA likely would not be used to attempt to compel actions by a non-US corporation acting outside the US, but may be used to control manufacturing activities taking place within the US, even if those activities are undertaken by a non-US corporation.

European Union

The EU does not have any specific legislation equivalent to the DPA, but individual Member States may have adopted their own equivalents.

That said, European Council President Charles Michel has publicly suggested that the EU could use a provision in the EU Treaties to adopt "urgent measures" in response to a shortfall in COVID-19 vaccine production. The provision in question, in Article 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("TFEU"), is generally viewed as a mechanism for the EU to rush emergency financial support for Member States. According to press reports, the Legal Service of the Council takes the view that Article 122 of the TFEU could also be used to force vaccine developers and manufacturers to share intellectual property or to compel those companies to ramp up vaccine production for supply to EU Member States.

People's Republic of China

Similar to the EU, the PRC does not have any legislation equivalent to the DPA; however, there are regulations, administrative measures, and judicial precedents in the PRC empowering the government to control, allocate, and prioritize production of essential products for epidemic prevention and control, as described below.

National Plan for Response to Public Health Emergencies (2006)

The National Plan for Response to Public Health Emergencies states that governments at all levels must gather all emergency materials and equipment as necessary in emergency handling. After the completion of the public health emergency response work, the government at each level must reasonably evaluate the materials urgently collected and requisitioned from relevant entities, enterprises, and individuals and offer compensation.

PRC Vaccine Administration Law

Article 66 of the Vaccine Administration Law recognizes vaccines to be included in the national strategic material reserves and requires the state to implement reserves at the central and provincial levels. Currently, there is no special law or regulation governing the procurement or restriction on national strategic material reserves in China.

PRC Drug Administration Law ("Drug Administration Law")

Article 92 of the Drug Administration Law provides that the government is entitled to carry out an urgent drug allocation in the event of serious disasters, epidemic outbreaks, or other emergencies- such as COVID-19.

PRC Drug Administration Law ("Drug Administration Law")

Article 92 of the Drug Administration Law provides that the government is entitled to carry out an urgent drug allocation in the event of serious disasters, epidemic outbreaks, or other emergencies- such as COVID-19.

PRC Foreign Investment Law

Article 20 of the Foreign Investment Law states that the state normally does not expropriate the investment of foreign investors. However, the state may expropriate or requisition the investment of foreign investors under special circumstances for the need of the public interest.

Government Notices

On the local level, multiple notices issued by the Chinese central government in early 2020 require (1) local governments to take charge of manufacturing epidemic prevention materials and (2) manufacturers to obey the centralized arrangement. Although they do not target COVID-19 vaccines or therapeutics, these notices may indicate an inclination of the Chinese government to control manufacturing and distribution of such vaccines and therapeutics.

EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATIONS FOR VACCINES AND THERAPEUTICS

Each of the major markets has the authority to temporarily authorize the distribution of drug products. In the PRC, such authority is generally limited to vaccines. In the US, EU, and UK, such authority applies more broadly to medicinal products. The US government also has the ability to temporarily authorize the use of approved medicines for unapproved uses.

United States

Emergency Use Authorization ("EUA")

The FDA has the authority to permit both approved and unapproved medical products for unapproved uses to be manufactured and distributed under specific conditions and labeling during the period of a declared pandemic or other health emergency.9 One such condition is that an agent (here, SARSCoV-2) can cause a serious or life-threatening disease or condition (here, COVID-19). An emergency declaration invoking the EUA authority was issued by the Secretary of HHS on February 4, 2020, for COVID-19. Since then, the FDA has issued hundreds of EUAs for COVID-19-related therapeutics, devices, diagnostics, and vaccines. If granted, an EUA is in effect only during the period specified in the declaration and an additional time period specified in the declaration for ensuring proper disposition of the product. Thus, an EUA is not a substitute for (and is not intended to delay) applications for actual clearance or approval. The FDA can revoke or terminate an EUA at any time.

European Union

Directive 2001/83/EC

Article 5(2) of Directive 2001/83/EC permits the EU Member States to temporarily authorize the distribution of unauthorized medicinal products in response to the spread of pathogenic agents, toxins, chemical agents, or nuclear radiation that may cause harm to human beings, such as the COVID-19 outbreak. The specific rules for the implementation of Article 5(2) supply programs are set out in the national laws of the EU Member States.

United Kingdom

Human Medicines Regulations

Regulation 174 of the Human Medicines Regulations is consistent with Article 5(2) of Directive 2001/83/EC and permits temporary authorization of a medicinal product in response to the confirmed or suspected spread of pathogenic agents. As mentioned earlier, the Human Medicines Regulations were amended on October 16, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Among other things, the amendment strengthened existing provisions that allow for the temporary licensing of medicines and vaccines. As a result, several COVID-19 vaccines have been granted temporary authorizations.

People's Republic of China

Vaccine Administration Law

The PRC's counterpart to the FDA, the National Medical Products Administration ("NMPA"), may authorize the emergency use of vaccines within a certain scope and time period in the case of any particularly serious public health emergency or any other emergency that poses a serious threat to public health-including COVID-19-pursuant to Article 20 of the Vaccine Administration Law. The application of such emergency use must be proposed by the National Health Commission as required for the prevention and control of the infectious disease. However, unlike the FDA's emergency authorization powers that apply broadly to all medical products, the NMPA's powers are limited to vaccines.

Under the Vaccine Administration Law and other relevant regulations, a vaccine that is urgently needed as a countermeasure against COVID-19 also qualifies for the following expedited regulatory approval pathways to accelerate its listing and sales:

- Priority Review and Approval: Both Article 96 of the Drug Administration Law and Article 19 of the Vaccine Administration Law permit priority review and approval of urgently needed new drugs for the prevention and treatment of serious infectious diseases.

- Conditional Approval: Article 20 of the Vaccine Administration Law permits conditional approval of vaccines urgently needed in response to a major public health emergency after being assessed by the NMPA. After receiving a conditional approval, the vaccine marketing authorization holder is required to complete the conditional approval criteria for marketing and post-marketing research work within a specified period stipulated by the NMPA.

- Exemption of Release Approval: Article 28 of the Vaccine Administration Law provides that, upon an approval from the NMPA, a vaccine developed in response to an emergency can be exempted from approval before the release of each batch to the market.

PRICE GOUGING

The PRC is the only major market with federal legislation that directly addresses price gouging. The US has typically regulated price gouging on the state level, while the EU and UK have used national competition laws to regulate price gouging. However, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, each of the major markets has implemented new guidelines or worked within the parameters of existing legislation to regulate the pricing of popular pandemic items like masks and hand sanitizer.

United States

Generally, price gouging in the US has been regulated under state law. States use a variety of legal authorities and enforcement postures to target price gouging. The US does not have a federal price gouging statute. However, on March 25, 2020, the Department of Justice ("DOJ") announced that it is using a provision of Title I of the DPA (referenced above) that prohibits "hoarding" to target companies that are allegedly price gouging for PPE, such as N95 masks.10 Apparently, the DOJ is interpreting the DPA's hoarding restrictions to also prohibit charging exorbitant prices for scarce commodities needed to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a novel use of the DPA that has emerged during the pandemic.

For more detail on price gouging, please see our advisory located on our website: https://www. arnoldporter.com/en/perspectives/publications/2020/04/covid-19-puts-spotlight-on-price -gouging.

European Union

Price gouging is addressed by EU authorities using the competition law rules and, more specifically, the fact that excessive pricing is an abuse of a dominant position under both EU competition laws and the national equivalents. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several European countries have regulated the prices of certain products, such as face masks and hand sanitizer, by setting maximum retail prices. The European Commission (the "Commission") and Member States' competition authorities have also indicated that they would closely and actively monitor the market to detect instances of undertakings [?] taking advantage of the crisis. As a result, several antitrust investigations were launched into price increases and output restrictions of healthcare materials and other products. However, excessive pricing cases have historically been rare and difficult for the authorities.

United Kingdom

After the Brexit transition period, UK competition rules are not expected to change in substance, at least in the short to medium term. Price gouging therefore continues to fall within the type of conduct that might constitute an infringement of national competition rules. In substance, high (or excessive) prices can give rise to an antitrust violation only if (i) the seller is in a dominant position, (ii) the price is excessive, and (iii) the price is unfair either in itself or in comparison with other products. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK competition regulator, the Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA"), has made monitoring price increases and tackling any form of price gouging one of its key objectives. As early as March 2020, an open letter to the pharmaceutical and food and drinks industries was issued to warn firms against capitalizing on the current situation by charging unjustifiably high prices for essential goods.

The CMA has so far opened four investigations into suspected excessive pricing by a number of UK retailers (including pharmacies) in relation to the price of hand sanitizer, which had increased up to almost 400% since the beginning of the pandemic. Additionally, in June 2020, the CMA issued a joint letter with the General Pharmaceutical Council encouraging all pharmacies to "ensure that their prices for essential products, including hand sanitizer, face masks and paracetamol, do not include higher than usual mark-ups, when compared to their pre-coronavirus mark-ups for those products and their mark-ups more generally." These investigations into excessive pricing have now been closed without an infringement finding. Thus, while the CMA has a high hurdle to overcome to find an infringement, it is clear that the CMA is actively monitoring the market and is willing to investigate allegations of excessive prices.

People's Republic of China

Price gouging is regulated in China through the PRC Price Law and its implementation rules, as well as competition laws and regulations. In response to COVID-19, the State Administration for Market Regulation issued a guideline on the implementation rules of the PRC Price Law on February 1, 2020. The guideline targets epidemic prevention products, including masks, antiviral medicine, disinfection and sterilization products, and relevant medical devices and equipment, and provides standards and examples for determining illegal price gouging activities.

COOPERATION BETWEEN COMPANIES

Each major market has implemented a framework to ensure expedited review of antitrust compliance for companies collaborating to help combat the COVID-19 pandemic. The US and European governments have established review procedures to evaluate COVID-19-related joint ventures and guidance for businesses seeking to collaborate on health- and safety-related projects during the pandemic. In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority has similarly issued guidance on COVID19-related business cooperation, while the UK government has provided for a number of exclusions in specific sectors from the application of UK competition law. In the PRC, the State Administration of Market Regulation has established expedited merger reviews, exemptions to certain competitor collaborations, and heavier penalties on certain antitrust violations in an effort to facilitate pandemic control and work resumption.

United States

On March 24, 2020, the US antitrust agencies (FTC Bureau of Competition and DOJ Antitrust Division) issued a joint statement11 detailing an expedited antitrust review procedure and providing guidance for businesses seeking to collaborate on health- and safety-related projects during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The agencies announced that they would accelerate their review of requests for FTC Advisory Opinions and DOJ Business Review Letters, which are part of a well-established procedure whereby firms or individuals submit proposals for joint ventures or other conduct to the agencies for evaluation and receive a response advising on whether the proposed conduct complies with US antitrust laws.

The agencies' responses times can vary, but typically the procedure takes several months. In the March 2020 joint statement, the agencies announced that, effective immediately, they would expedite their review of proposals involving cooperative conduct related to addressing COVID-19 and its aftermath. Specifically, the agencies stated that they would "aim to respond expeditiously" to all COVID-19- related requests for Advisory Opinions or Business Review approvals, and to resolve those requests addressing public health and safety within seven calendar days of receiving all necessary information.

The agencies also signaled that they would "account for exigent circumstances" when evaluating efforts to mitigate the spread and impact of COVID-19. The joint statement recognizes that healthcare providers or facilities may need to cooperate to provide communities with necessary resources or services (e.g., PPE, other medical supplies) and that certain businesses may need to temporarily combine their manufacturing or logistical capabilities to facilitate the production or distribution of COVID-19-related supplies: "These sorts of joint efforts, limited in duration and necessary to assist patients, consumers, and communities affected by COVID-19 and its aftermath, may be a necessary response to exigent circumstances that provide Americans with products or services that might not be available otherwise." The agencies also noted that the antitrust laws already allow for collaboration in many circumstances (e.g., research and development efforts, sharing technical know-how and clinical best practices, certain joint purchasing arrangements) and that "many types of collaborative activities designed to improve the health and safety response to the pandemic would be consistent with the antitrust laws."

European Union

Temporary Framework for assessing antitrust issues related to business cooperation in response to situations of urgency stemming from the current COVID-19 outbreak ("Temporary Framework")

On April 8, 2020, the European Commission published a Temporary Framework for the assessment of horizontal cooperation during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Temporary Framework sets out the key criteria the Commission will take into account when assessing certain types of cooperation and establishes a procedure for the provision of guidance for specific conduct by way of an ad hoc comfort letter.

The Temporary Framework applies to conduct that is necessary to ensure the supply and adequate distribution of essential scarce products and services, including notably "medicines and medical equipment that are used to test and treat COVID-19 patients or are necessary to mitigate and possibly overcome the outbreak." The Temporary Framework sets out certain limited forms of cooperation (e.g., reallocating stocks, switching production lines, aggregating production, sharing information on shortage risks) that the Commission does not consider to give rise to competition issues provided they are subject to sufficient safeguards.

Under normal circumstances, such measures would in principle be problematic under the competition rules. However, in light of the current exceptional circumstances, the Commission does not consider them to be an enforcement priority, provided the measures are: (i) objectively necessary to address or avoid a shortage of supply of essential products of services; (ii) temporary; and (iii) not exceeding what is strictly necessary to address or avoid the shortage of supply. The fact that such cooperation is encouraged or requested by a public authority is also a relevant factor. The Temporary Framework recommends that companies document their exchanges and agreements so they can be made available to the Commission on request.

Additionally, the Commission created a procedure allowing it to provide ad hoc guidance on specific, temporary cooperation projects by means of comfort letters. The first comfort letter was issued on April 8, 2020 to Medicines for Europe, an association of generic pharmaceutical companies, for a cooperation project involving information sharing aimed at managing the risk of shortages of medicines needed in intensive care units for the treatment of COVID-19 patients. The Commission concluded that the cooperation was justifiable under the Temporary Framework but imposed a number of conditions: (i) the project must be open to any interested pharmaceutical company; (ii) meeting minutes must be kept and agreements must be shared with the Commission; (iii) only indispensable information may be shared; (iv) information must be collected either by the association or a third party; and (v) information may be shared in aggregate form only.

Informal guidance from the European Commission on specific initiatives can be found at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/coronavirus.html.

United Kingdom

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the CMA has issued a number of measures responding to the challenges posed by the pandemic. The key message is that while competition law is very much still in force, it should not prohibit actions that are necessary to alleviate urgent situations relating to COVID-19 (such as permitting necessary coordination in order to ensure the supply and fair distribution of scarce products to consumers).

In an effort to give businesses greater flexibility to engage in targeted cross-competitor cooperation, on March 25, 2020, the CMA issued formal guidance on cooperation during the pandemic. The CMA reassured businesses that it will not take enforcement actions against temporary, necessary cooperation aimed at avoiding shortages or meeting the supply needs of essential products and services arising as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it also stressed that businesses do not have a "free pass" to engage in anti-competitive conduct and exploit the crisis as a cover for nonessential collusion. Underlying the CMA's approach to enforcement is the potential for coordination to cause harm to consumers or to the wider economy, particularly where the collaboration involves coordination on pricing.

In parallel, the UK government has issued, through ad hoc legislation, a number of exclusions in specific sectors from the application of UK competition law. In particular:

- In order to assist the UK National Health Service ("NHS") in addressing the effects of COVID-19 on the provision of healthcare services, independent healthcare providers and NHS bodies have been permitted to, among other things, exchange information on capacity, share staff and facilities, and divide activities within particular geographic areas.

- Ferry companies operating services on the Isle of Wight and the UK mainland have also been permitted to coordinate on timetables and routes as well as deployment of staff and vessels.

- A package of measures (now withdrawn) was adopted to alleviate shortages and/or excess demand in the grocery sector, allowing some cooperation among grocery suppliers and among logistic service providers-including on staff deployment, joint purchasing, division of activities in a particular area, and storage and vehicle capacity.

- Another package of measures (also now withdrawn) temporarily permitted collaboration between dairy farmers and producers to avoid a surplus of milk-including sharing information on surpluses, stock, capacity, and demand as well as coordinating to reduce production.

Importantly, information sharing and/or coordination on prices and costs have not been permitted under any of the existing or withdrawn exclusions. It is also worth noting that the above exclusions are only capable of disapplying UK competition rules; no such exclusions are available for conduct having an effect outside the UK, including trade with EU Member States.

To ensure effective monitoring and prompt action with respect to competition concerns arising from the current crisis, the CMA has also set up a COVID-19 taskforce as well as a dedicated online service to report allegedly unfair practices. In this context, the CMA has been a very valuable point of contact for businesses and has shown a high degree of pragmatism. In our direct experience of dealing with the CMA's taskforce, we have found its dialogue with companies dynamic and responsive. That said, the key takeaway is that the CMA is closely watching market developments to monitor where government action may be required.

People's Republic of China

On April 4, 2020, China's antitrust regulator, the State Administration of Market Regulation ("SAMR"), released a Notice on Supporting Anti-Monopoly Law Enforcement for Pandemic Prevention and Control and Resumption of Work and Production ("Notice"). The Notice, among other things, provides for expedited merger reviews, exemptions to certain competitor collaborations, and heavier penalties for certain antitrust violations.

In its Notice, SAMR established a green channel to expedite merger reviews in the following areas: (i) sectors closely related to the control of the pandemic and daily necessities, such as manufacturers of pharmaceuticals and medical devices, food, transportation, wholesale, and retail; (ii) sectors severely impacted by the pandemic, such as restaurants, accommodations, and tourism; and (iii) transactions that facilitate the resumption of work and production.

SAMR further indicated that it will exempt certain competitor collaborations from antitrust scrutiny to help combat the pandemic and resume work and production, including collaborations to improve existing technology and to research and develop new products related to pharmaceuticals, vaccines, test technology, medical devices, and PPE. SAMR noted that in order to qualify for the exemptions, companies must continue to meet the requirements under Article 15 of PRC's Anti-Monopoly Law, which requires the companies to demonstrate that the concluded agreement will not materially restrict competition in the relevant market and will enable consumers to share the benefits of the collaboration.

SAMR also called for accelerated investigation and heavier penalties imposed by provincial authorities on antitrust violations hampering pandemic control and work resumption if the violation occurs in sectors closely related to the control of the pandemic (such as manufacturers of masks, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and disinfectants), public utilities (such as suppliers of water, electricity, and gas), and other sectors closely related to people's livelihood.

EXPORT CONTROL

Each major market has implemented or updated its export control regime in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While each major market has restricted the export of certain medical supplies, the EU and PRC have implemented additional restrictions on the export of COVID-19 vaccines.

United States

The US has the most comprehensive export control regime of the major markets. Three separate legal regimes currently govern US exports: (1) the International Traffic in Arms Regulations ("ITAR"); (2) the Export Administration Regulations ("EAR"); and (3) new COVID-19-related restrictions on the export of certain healthcare and medical resources implemented by the Federal Emergency Management Agency ("FEMA").

ITAR

Without a license or other authorization, the ITAR restricts the export, reexport, or in-country transfer of defense articles and services on the US Munitions List, including hardware, software, and technical data. Certain biological and biotech-related items are controlled under the ITAR, but not "biological agents," which are certain listed pathogens that have been non-naturally genetically modified to increase persistence in the environment or the ability to overcome standard immunity or medical countermeasures. Sars-Cov-2, whether or not non-naturally genetically modified, is not currently subject to any controls under the ITAR. There may be controls on other genetically modified pathogens used for research.

EAR

Similarly, without a license or authorization, the EAR restricts the export, reexport, or in-country transfer of commodities, software, and technology on the Commerce Control List, including certain biological items. The list also covers chemical agents and other items that may be used in connection with biotech research. Unlike the ITAR, the list of controlled biological items includes naturally occurring pathogens, including many viruses, genetic elements of such viruses, and vaccines for such viruses. The list includes "severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-related coronavirus)."

However, the Commerce Department, which implements the EAR, considers Sars-Cov-2 to be an entirely distinct biological item. Therefore, the Commerce Department has issued guidance that SarsCov-2 is not subject to EAR controls on "SARS-related coronavirus" and instead is controlled at a level that would restrict export only to embargoed countries such as Cuba, Syria, Crimea, and North Korea (a level that applies equally to essentially any non-listed item in the US, including pencils, furniture, etc.). Therefore, there are currently no applicable controls on the export of Sars-Cov-2, its genetic elements, or related vaccines. The Commerce Department's guidance on Sars-Cov-2 indicates that the EAR may eventually determine that the virus and related items should be controlled at a higher level where a license may be required for any export, including to the UK. Furthermore, other biological or chemical elements of vaccines or therapeutics may be subject to higher restrictions. For example, certain viruses used to activate genes in research are subject to higher controls, as are certain viral vectors used in vaccines. Accordingly, any specific scope of research should be evaluated before export.

Finally, it is worth nothing that some pandemic-related equipment can be controlled at a higher level than the products themselves. For example, certain sophisticated storage tanks that may be used to transport sensitive pharmacological products may require a license for export to most destinations because of the potential use of such tanks for chemical weapons purposes.

COVID-19-Related FEMA Rules Blocking Exports of PPE

On April 10, 2020, FEMA issued the first of several temporary final rules allocating "for domestic use" certain PPE designated as "covered materials" and restricting exports of "covered materials" without explicit approval by FEMA. These covered materials include N95 filtering facepiece respirators; other filtering facepiece respirators (e.g., those designated as N99, N100, R95, R99, R100, P95, P99, or P100); elastomeric, air-purifying respirators and appropriate particulate filters/cartridges; PPE or surgical masks; and PPE or surgical gloves. The list of items now also includes surgical gowns and surgical isolation gowns as well as syringes and hypodermic needles (whether distributed separately or attached together) needed to administer the COVID-19 vaccines (either piston syringes or hypodermic single lumen needles with a safety feature). FEMA has stated that shipments of specified needles and syringes will be held and returned to the US supply chain only if there is a critical need for such medical equipment to vaccinate the US population against COVID-19.

These FEMA export restrictions are subject to a number of exemptions, including (i) intracompany transfers of covered materials by US companies from domestic facilities to company-owned or affiliated foreign facilities; (ii) shipments of covered materials that are exported solely for assembly in medical kits and diagnostic testing kits destined for US sale and delivery; and (iii) sealed, sterile medical kits and diagnostic testing kits where only a portion of the kit is made up of one or more covered materials that cannot be easily removed without damaging the kits. Another exemption allows for exports to customers abroad, which must meet certain historical supply criteria.

European Union

Regulation (EU) 2015/479 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 2015 on common rules for exports ("Regulation (EU) 2015/479")

Article 5 of Regulation (EU) 2015/479 governs the common EU rules for exports and gives the Commission the power to require authorization for the exports of certain goods. This applies in critical situations resulting from shortages of essential products. The Commission used this mechanism during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic, subjecting the export of PPE to prior authorization for the period from March to May 2020. In January 2021, the Commission adopted an export transparency and export authorization mechanism applicable to COVID-19 vaccines before they are exported from the EU. The measure is due to end on March 31, 2021.

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/111 of 29 January 2021 making the exportation of certain products subject to the production of an export authorization ("Implementing Regulation 2021/111")

On January 29, 2021, the European Commission adopted Implementing Regulation 2021/111, creating a temporary export authorization mechanism for COVID-19 vaccines purchased by the EU under Advance Purchased Agreements ("APAs").

The Commission has insisted that the new rules are mainly designed to ensure transparency about the quantities of produced and delivered vaccines covered by APAs, particularly so that manufacturers do not export vaccines required to implement the APAs, without impacting the EU's international commitments to equitable access.

The new rules, however, subject exports of vaccines outside the EU to specific authorizations, which are issued by the competent authorities of the EU Member States in which the vaccines were manufactured. Authorizations can be granted only for exports that do not pose a threat to the execution of the APAs, as concluded by the Commission on behalf of the Member States.

Authorization requests must be submitted to the individual Member State for an initial assessment; however, authorization is overseen by the Commission. Member States must notify the Commission of applications for export authorizations and provide draft decisions. If the Commission disagrees with a Member State's recommendation, it may issue an opinion, which the Member State must follow.

Manufacturers of vaccines covered by the APAs must, along with their first request for authorization, provide a significant amount of information, including data concerning their exports in the three months prior to entry into force of the new Regulation (as of October 29, 2020) (i.e., volume of exports, final destinations and recipients, and a precise description of the products) as well as information on the number of vaccine doses under the APAs distributed in the EU since December 1, 2020, broken down by Member State.

Some exports are exempted from the new authorization mechanism. These include: (i) exports of vaccines purchased and/or delivered through COVAX; (ii) exports to low- and middle-income countries; (iii) exports in the context of a humanitarian emergency response; and (iv) exports of vaccines purchased by Member States under the APAs and resold or donated to third countries.

The new mechanism is expected to remain in force until March 31, 2021, but it can be extended.

United Kingdom

Restrictions on the export of PPE products were implemented by the UK in March 2020 in accordance with European Commission Implementing Regulation 2020/568. The Implementing Regulation expired in May 2020 and was not renewed. Following the end of the Brexit transition period on December 31, 2020, EU laws no longer apply to the UK.

The UK government has restricted parallel exports (both to the European Economic Area and exEuropean Economic Area countries) and hoarding (i.e., withholding by wholesale dealers) of some medicines in order to meet the needs of UK patients. The list of products to which these restrictions apply is regularly updated, most recently on December 22, 2020: https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/medicines-that-cannot-be-parallel-exported-from-the-uk. Wholesalers may continue to withhold medicines as part of stock management arrangements agreed upon with marketing authorization holders, which is not considered to be hoarding. They may also continue to maintain stockpiles built up at the request of the Department of Health and Social Care in connection with Brexit preparations.

Import duty and value-added tax payments are waived for public or charitable organizations (e.g., NHS hospitals) that import protective equipment, certain medical devices, and other specified products for use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Goods can be imported on behalf of a public or charitable organization if they are to be donated or sold (directly or indirectly) to such organizations.12

People's Republic of China

Under the Vaccine Administration Law and the quarantine regulations, export of vaccines from China requires approval from the NMPA and quarantine inspection. The State Council can restrict or prohibit the export of drugs in shortage. Since April 1, 2020, the Chinese government imposed export controls on Chinese-manufactured COVID-19 medical devices, including COVID-19 detection reagents, medical masks, medical protective clothing, ventilators, and infrared thermometers. Exporters must declare that the products have obtained a medical device registration certificate issued by the NMPA and meet the quality standard requirements of the importing country.

Footnotes

1. Health and Human Services Department, Declaration Under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act for Medical Countermeasures Against COVID-19 (March 17, 2020), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/17/2020-05484/declarationunder-the-public-readiness-and-emergency-preparedness-act-for-medical-countermeasures. Amendments to the Declaration and HHS Advisory Opinions relating to the PREP Act can be found at https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/prepact/Pages/default.aspx.

2. These UK regulations are consistent with EU legislation, but may diverge from EU law in the future, depending on post-Brexit changes.

3. GOV.UK, Vaccine Damage Payment, https://www.gov.uk/vaccine-damage-payment/eligibility.

4. For claims brought under the Consumer Protection Act 1987 ("CPA," which implements the EU Product Liability Directive 85/374/EEC in the UK) that the product in question was defective.

5. See, e.g., Loveday v. Renton (No 1) 1990 1 Med LR". (holding that the claimant failed to prove on the balance of probability that pertussis vaccine can cause permanent brain damage in young children). Causation issues also proved fatal to the measles, mumps, and rubella group litigation in the late 1990s and 2000s

6. Unlike the PREP Act, which applies broadly to vaccines and therapeutics, the Vaccine Administrative Law applies only to vaccines. Further, the law does not provide immunity for vaccine or therapeutic liability.

7. Vaccination abnormal reaction, as defined by the Vaccine Administration Law, refers to adverse drug reactions of qualified vaccines that cause damage to tissues, organs, and functions of recipients during a standard vaccination process or after a standard vaccination, when the parties involved are not at fault.

8. 50 U.S.C. § 4501 et seq.

9. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act § 564, 21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3.

10. Department of Health and Human Services, Notice of Designation of Scarce Materials or Threatened Materials Subject to COVID-19 Hoarding Prevention Measures Under Executive Order 13910 and Section 102 of the Defense Production Act of 1950 (March 25, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/file/1264276/download.

11. Department of Justice, Joint Antitrust Statement Regarding COVID-19 (May 1, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/atr/joint-antitrust-statementregarding-covid-19.

12. GOV.UK, Guidance: Pay no import duty and VAT on medical supplies, equipment and protective garments (COVID-19) (March 31, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/guidance/pay-no-import-duty-and-vat-on-medical-supplies-equipment-and-protective-garments-covid-19.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.