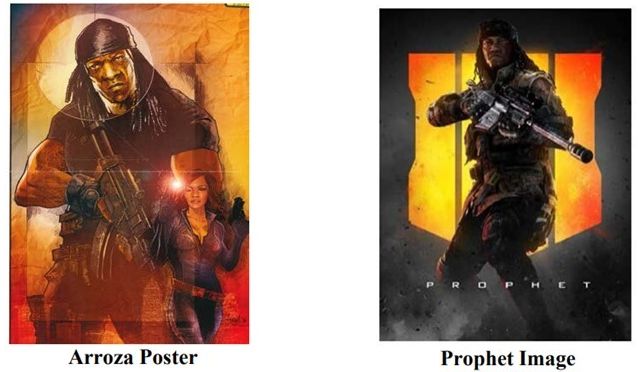

Retired professional wrestler Booker T. Huffman (professionally known as Booker T), and developer of the Call of Duty video game franchise, Activision, faced-off in a copyright dispute in the Eastern District of Texas. The case centers on allegations that Activision infringed Booker T's copyright in a poster (the "Arroza Poster") he used to promote his comic, G.I. Bro and the Dragon of Death. The comic stars a "special operations hero called G.I. Bro," which bears a strong resemblance to Booker T and one of his in-ring personas, "G.I. Bro." Booker T commissioned the poster in 2015 from the artist, Erwin Arroza, to promote the comic, and distributed copies of the poster at comic conventions and other events.

In an order addressing a wide-ranging series of multiple consolidated motions to dismiss, Magistrate Judge Payne recommended denying Activision's motions for summary judgment on all grounds but one. If the recommendation is adopted, it will clear the way for a rumble between heavyweights from two branches of the entertainment industry: pro wrestling and gaming.

Activision released Call of Duty: Black Ops 4 in 2018, a prequel to the third Black Ops game. It features a younger, pre-cybernetics version of shared character David "Prophet" Wilkes. Activision commissioned artwork depicting the Prophet, which included hiring live models for photoshoots. This effort resulted in various promotional posters, billboards, and special edition packaging, that include the specific "Prophet Image" at issue in the case.

|

Activision moved for summary judgment on multiple grounds, each addressed separately below.

Standing to Sue - Whether Booker T Owns the Rights to GI Bro

Activision argued Booker T had no standing to sue, because he had assigned the rights to the character "G.I. Bro" to the WWE. Booker T countered, first, that his registration of the comic and drawings with the Copyright Office is enough evidence of ownership to survive summary judgement, second, that WWE does not assert ownership of the "G.I. Bro" comic book character, and third, the scope of Booker T's agreement with WWE covered only the "G.I. Bro" wrestling persona and not the "G.I. Bro" comic book character.

Magistrate Judge Payne disagreed with Booker T's first two arguments. First, he determined that Booker T's ownership of the copyright, recorded in the registration certificates, can be rebutted. Second, he recognized that Activision could challenge whether the contract assigned the copyrights to the WWE, even if the agreement did not involve Activision. Thus, Activision may raise this evidence at trial.

On the third argument, Judge Payne recommended there is an issue of fact as to whether the comic book "G.I. Bro" and the wrestling "G.I. Bro" are the same. Thus, the jury should decide. Specifically, the issue is whether the Booker T-WWE contract conveyed ownership of the comic book "G.I. Bro" to WWE as a piece of intellectual property "in connection with the business of professional wrestling." Because Judge Payne determined "in connection with the business of professional wrestling" to be ambiguous, he recommended the scope of WWE and Booker T's contract (and its application to the comic book version of "G.I. Bro") should be resolved by the jury.

Copying - Whether Activision Had Access to the Arroza Poster and Whether Activision Created an Independent Creation

Activision argued that Booker T failed to provide evidence that Activision actually used the copyrighted material to create the Prophet Image. To prove copying, a Plaintiff has two options. First, it can prove copying by showing the defendant had access to the copyrighted work prior to creation of the infringing work, and that there is a "probative similarity" between the two works. If access cannot be established, a plaintiff may be able to establish copying by showing that there is a "striking similarity" between the works at issue.

Regarding proof of access, Judge Payne determined that evidence that an Activision employee had attended Comic-Con events was sufficient to survive summary judgement because Booker T had displayed the Arroza Poster at those events. The Court recommended that this evidence is sufficient to present a genuine dispute of material fact suitable for the jury.

Regarding similarity, Activision argued that the Prophet Image was the result of independent creation based on a photoshoot, precluding a finding of striking similarity. Activision also argued that the Prophet Image is sufficiently different from the Arroza Poster to preclude a finding that the images are strikingly similar. Considering independent creation, Judge Payne rejected Activision's argument, determining that Activision's process included collecting references for inspiration, and that the final image was not based on a single photo. This, the Court decided, created an issue of genuine material fact of independent creation. In considering whether the works are strikingly similar, the Court rejected Activision's argument, finding that the two images "clearly share similarities and potentially even have striking similarities." Thus, the jury should make the final decision on similarity.

Copyright Management Information (CMI) - Removal, Falsification, Intent, and Scope

Activision also moved to dismiss Booker T's claims regarding the removal of Copyright Management Information, or CMI. Booker T identified the CMI to be the marking of "Arroza, '16" on the Arroza Poster. Activision contended it did not unlawfully remove CMI under 17 U.S. Code § 1202(b) by not including Arroza's signature in the Prophet Image. Judge Payne agreed with Activision that Booker T provided no evidence showing removal of the CMI. Specifically, Judge Payne ruled that the "removal" provisions of section 1202 refer to altering CMI that already exists in an image, not failing to include truthful CMI in a copy.

However, Judge Payne disagreed with Activision's arguments that Activision could not have distributed false CMI under 17 U.S. Code § 1202(a). Activision argued that the false CMI provision applies when direct copies of an "original work" are made with a different CMI. But Judge Payne determined the statute should not be read so narrowly, stating that a defendant could violate the statute by placing a false CMI on a derivative work or "a defendant's own work." Thus, he recommended that the issue of false CMI on the Prophet Image should also be determined by the jury.

Judge Payne disagreed with Activision's remaining arguments, ruling as follows: first, that one of Activision's special edition cases could violate 17 U.S. Code § 1202(a) even though the allegedly false CMI is on the disk inside the game package, while the Prophet Image is on the package itself; second, that Booker T should have the opportunity to prove Activision's intent to violate the CMI statute circumstantially; and third, that the jury should be able to determine whether Black Ops 4 sales are related to Activision's use of the Prophet Image for the calculation of damages.

Activision has filed objections to the Recommendation and Report, which the Court has not yet considered.

The case is Huffman v. Activision Publ'g, Inc., No. 2:19-cv-00050 (E.D. Tex. Dec. 14, 2020).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.