For nearly two decades, the "transformative use test" has been a staple of fair use analysis, and particularly in the Second Circuit. The Copyright Act, however, uses the word "transformative" not in the section on fair use but in defining derivative works. The distinction is critical: fair use is a complete defense to infringement, while creation of an unauthorized derivative work is itself infringement. Courts, practitioners, and creators alike have struggled to draw the line: when is a transformative use an infringing derivative work versus fair use?

In a recent decision, the Second Circuit took a step towards drawing that line with a little more clarity, finding pop artist Andy Warhol's use of a copyrighted photograph of musician Prince in a series of prints was not "transformative" and did not constitute fair use. See The Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, Case No. 19-2420 (2d Cir. March 26, 2021). Thus concluding the latest chapter in the much-watched copyright dispute between the Andy Warhol Foundation and celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith.

Background

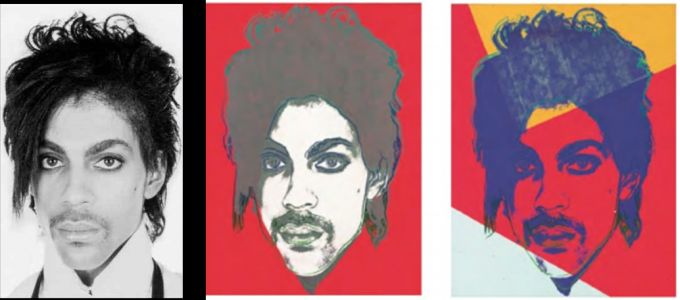

At the heart of this dispute is a 1981 photograph of Prince taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith in her studio, in which she holds the copyright. In 1984, Goldsmith's agency licensed the photograph to Vanity Fair magazine for use as an artist reference. Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, the artist Vanity Fair had commissioned was Andy Warhol. Further unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol relied on the photograph not only for the one piece Vanity Fair had commissioned, but also created a series of fifteen additional prints – all of which featured Prince's face as it appeared in the photograph, in Warhol's signature aesthetic style. A comparison of the works is displayed below.

In 2019, the district court granted summary judgment in favor of the Warhol Foundation, finding the use of the photograph was fair use. That decision was based primarily on a finding that Warhol's Prince series aesthetically transformed the original work. Specifically, Judge Koeltl of the Southern District of New York found Warhol's work transformed the original Prince image from that of a "vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure." The well-known and distinctive nature of Warhol's work also factored into the court's analysis. Judge Koeltl noted "each Prince series work is immediately recognizable as a 'Warhol' rather than as a photograph of Prince — in the same way that Warhol's famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as 'Warhols,' not as realistic photographs of those persons." The decision created concern among some copyright scholars that the "transformative use test" had been stretched too far. For additional information, see our prior coverage.

Second Circuit Decision

The appeal was heard by a three-judge Second Circuit panel, consisting of Judge Gerard Lynch, Judge Richard Sullivan, and Judge Dennis Jacobs. Delivering the Court's opinion, Judge Lynch determined the district court had too broadly and subjectively analyzed whether Warhol's work was "transformative." Specifically, Judge Lynch wrote that though Goldsmith and Warhol may have had different artistic intentions, "whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic – or for that matter, a judge – draws from the work. Were it otherwise, the law may well recognize any alteration as transformative."

Rather than "assum[ing] the role of art critic and seek[ing] to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue," Judge Lynch stated the court must examine how the works may "reasonably be perceived," and must determine whether the secondary work's use of its source material is in service of a "fundamentally different and new" artistic purpose. For a purpose to be "fundamentally different and new," the Court found that though the primary work need not be "barely recognizable" within the secondary work, the secondary work must "at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist's style on the primary work."

Here, the Court found Warhol's series failed to meet this minimum requirement. Though the Warhol work was created in Warhol's signature aesthetic style, the Court found it was still plainly an adaptation of the Goldsmith photograph. The artists' intentions notwithstanding, both works could reasonably be perceived in the same manner – as recognizable depictions of Prince. And further, the overarching purpose and function of the two works was identical, since they were portraits of the same person.

Crucially, the Court noted Warhol's work "retain[ed] the essential elements of the Goldsmith photograph" without adding to or modifying those elements. Warhol's only changes to the original photograph involved magnifying some elements of the source material (like contrast and lighting) and minimizing others. Ultimately, rather than creating a transformative derivative work, the Court determined Warhol just recast the same work in a different aesthetic.

The Court also rejected the district court's reasoning that the distinctiveness and recognizability of Warhol's style should factor into the analysis. The Court opined that adopting this logic would "inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege" whereby the more famous or recognizable an artist, the greater leeway the artist would have to appropriate others' work. Even though The Irishman is recognizably "a Scorsese," the Court observed this does not absolve Martin Scorsese of the obligation to license the original book on which it is based. Likewise, the distinctive nature of "a Warhol" does not relieve Andy Warhol of the duty to license original photographs on which his work is based.

The Court concluded the other fair use factors weighed against the Warhol Foundation, too. Goldsmith's original photograph was both creative and unpublished, favoring Goldsmith in the "nature of the work" factor. The "amount and substantiality" factor also favored Goldsmith; Warhol's work borrowed so significantly from her photograph that the end product was not merely a screenprint based on a photograph of Prince. Instead, it was a screenprint based on a specific photograph – Goldsmith's photograph. And lastly, despite finding the markets for the Goldsmith photograph and Warhol prints did not meaningfully overlap, the Court determined Warhol's use harms Goldsmith's potential market in a different way – by threatening Goldsmith's actual or potential licensing revenue. Because both images are depictions of the same person, both Goldsmith and the Warhol Foundation have sought to license (and have successfully licensed) their respective depictions of Prince to accompany articles about him.

Implications for the Transformative Use Test

Warhol v. Goldsmith is not the only recent decision taking a narrower reading of the transformative use test. Just a few months ago, in Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix LLC, the Ninth Circuit reversed a district court decision finding a mashup parody of Star Trek and Dr. Seuss's Oh, the Places You'll Go! constituted transformative fair use. As in Warhol, the Ninth Circuit found that by merely using Dr. Seuss and Star Trek material without critiquing or commenting on it, the defendant's work did nothing more than repackage the original source material in a different form, which was not enough to be considered "transformative" for fair use purposes.

Warhol and Dr. Seuss may represent a trend towards a more restrictive reading of the transformative use test – one less grounded in the court's subjective interpretation of the intent behind the works. Instead, these recent decisions suggest that the transformative use test may increasingly turn on a more objective evaluation more akin to the reasonable observer or reasonable listener test of substantial similarity analysis by "examining how [the work] may 'reasonably be perceived.'"

However, in a decision just issued in Google v. Oracle, the Supreme Court took an arguably broader reading of the transformative use test in the software context. In Google v. Oracle, the Supreme Court determined Google's use of elements of Oracle's Java code to build the Android system was transformative and fair use as a matter of law. The Court held that, though Google used portions of Oracle's code "for the same reason" the code was originally created, it was nonetheless transformative because Google sought to "create new products" with it. The Court found that was "consistent with that creative 'progress' that is the basic constitutional objective of copyright itself." This is unlike the approach taken in Warhol and Dr. Seuss, where courts focused more on reasonable perception of the work, rather than on the creators' intent. Arguably, the Google v. Oracle holding may be limited to the software context where "virtually any unauthorized use of a copyrighted computer program ... would do the same [thing]." Nonetheless, Justice Thomas argued in dissent that the majority's definition of transformative "wrongly conflates transformative use with derivative use" and would "eviscerate[] copyright."

Undoubtedly, the Supreme Court's decision here may further redirect the course of the transformative use test going forward. It is back in the hands of the lower courts, commentators, and practitioners to determine whether Google v. Oracle represents a broad retrenchment of the transformative use test or signals different approaches depending on the type of work being analyzed.

Second Circuit Finds Andy Warhol's Use Of Prince Photograph Wasn't All That Transformative After All

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.