Private business owners are wondering, “Should I switch my business to a C corporation?”

“It’s déjà vu, all over again!”

For the first time in a decade, the top rates for individual and corporate income tax are not equal. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 returned the top individual rate to 39.6% (not counting new Medicare taxes), while the top corporate rate remains unchanged at 35%.

And the rate changes may not be over. Lawmakers have been discussing tax reform for much of the past year, and the focus has largely been on lowering the corporate tax rate. This may cause privately held business owners to re-examine the tax structure of their businesses. This article focuses on the important considerations for that analysis.

How we got here

Before 1982, privately held businesses were typically owned as C corporations. The top individual rate on ordinary income was 70%, while the top corporate rate was only 48%. But it was not that simple. Those were the days of things like the “maxi-tax,” which limited the rate on personal service income to 50%1 and “preferred stock recaps.”

There were games to avoid double taxation and lots of rules to catch the offender, such as “personal holding company tax,” “accumulated earnings tax,” and “unreasonable compensation.”

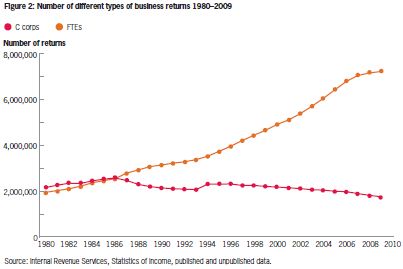

The gulf between high individual rates and much lower corporate rates invited complex tax planning.2 There were games to avoid double taxation and lots of rules to catch the offender, such as “personal holding company tax (PHC tax),” “accumulated earnings tax,” and “unreasonable compensation.”3 In 1982, the rate gap was lowered to 2%, yet there was very little movement away from choosing the C corporation entity for privately owned businesses. Then in 1986, with the sweeping changes of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, individual rates began to tumble and, all of a sudden, the S corporation was in bloom.

The evolution of entity choice continued as S corporations gradually became more popular than C corporations for privately held businesses. Then, when laws such as Wyoming’s 1977 Limited Liability Company Act made limited liability protection available outside of the S and C corporation structure, there was a steady movement toward partnerships and limited liability companies (LLCs) taxed as partnerships. Together, the growing population of S corporations, partnerships and LLCs taxed as partnerships represent today’s flow-through entities (FTEs). FTEs are not taxed at the entity level. Rather owners are taxed on income only at the individual level.

Many family-owned businesses resisted the conversion from C corporations because of concerns about the administrative costs, “disclosure” of their earnings to family members and taxes levied at the conversion from C to S (such as the LIFO recapture and “built-in gains” taxes). But new legislation continued to drive the movement to S corporations, including easing the restrictions regarding 1) types of owners (trusts, employee stock ownership plans), 2) limits on the number of owners, and 3) allowing for domestic subsidiaries and foreign “subsidiaries” (treated as divisions by “checking the box”). By 2012, the closely held C corporation, but for a few special circumstances, had become very uncommon.4

In the end, the equivalent tax rates between C corporations and FTEs offered a fair playing field that discouraged the use of complicated transactions and structures that existed when rates were different. Further, the tax benefits available for FTEs, particularly when selling,5 allowed some of the country’s most entrepreneurial and dynamic businesses to compete with larger public competitors.

Now, the administration and both parties in Congress are discussing tax reform to lower tax rates. Unfortunately, much of the focus has been on lowering only the statutory rate for C corporations. Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle generally agree that U.S. corporate rates are no longer competitive with our worldwide trading partners. There is less agreement on how to handle the individual tax rates that affect FTEs. It is possible the current rate differential will get larger if lawmakers reduce corporate rates while leaving individual rates untouched.

So what’s an owner to do? If Congress enacts a lower corporate tax in the 28% range, with individual taxes at 39.6%, should private business owners consider violating a rule we have been teaching students of tax for the last decade: NEVER make your business a C corporation if it is privately held and if you can possibly avoid it? Could this really be happening?

This article examines this issue from a myriad of points in time in a business life cycle that a privately held FTE business owner must consider, such as:

-

starting the company,

-

growing the company,

-

harvesting value through dividends, and

-

either selling the company or passing the company on to the next generation.

The assumptions used for our calculations in the various scenarios presented are likely different than the reader’s circumstances — perhaps by a little or maybe even by a lot. The reader is warned there is NO substitute for doing this analysis yourself, using sensitivity analysis to model your circumstances. Even then these decisions can sometimes be less than obvious. We seek here to define the outer edges, the obvious choices, and help you understand the nuances of circumstances in between.

Defining our audience — privately owned business: Where do private equity- and venture capital-backed portfolio companies fit in?

Privately held businesses consist primarily of three ownership types:

-

The family-owned business

-

The management-owned business

-

Private equity- and venture capital-owned portfolio companies

This article is aimed at the first two groups of owners, who face many similar decisions. While private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) portfolio companies are privately held, due to complex rules governing the taxation of the investors in these funds — particularly pensions, foundations and foreign owners — PE/VC portfolio companies are generally C corporations. So for these businesses, corporate rate reduction is a pure win, much as it is for publicly held companies.

Modeling out choice of entity — FTE versus C corporation

C corporation rates are now lower than individual rates and may be going lower still.

There are three fundamental tax issues privately owned FTE businesses should consider in the face of potential lower rates for C corporations:

-

Taxable versus tax-free distribution of earnings

-

The power of selling assets out of an FTE

-

More tax-efficient gifting and other estate-planning techniques available to FTEs

These concepts should be weighed in the context of cash flow needs, the ability to satisfy debt covenants, business growth plans, succession planning and other specific goals each company has. We will explain how each concept impacts the difficult entity choice between a C corporation and an FTE.

Déjà vu

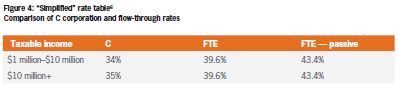

So, we are back to where we were in the mid-80s. C corporation rates are now lower than individual rates and may be going lower still. The current top C corporation rate is 35%, but income under approximately $15 million is generally taxed at a 34% rate. FTE income is taxed only at the individual level. The top individual rate on ordinary income is 39.6% beginning in 2013, plus an extra 3.8% for income subject to the new Medicare tax. The top rates on dividends and capital gains are 20%, and also will generally be subject to the new 3.8% Medicare taxes. The Medicare tax is effective only above high-income thresholds but generally applies to any passive income from an FTE, plus dividends, capital gains, rents and royalties, unless they are derived in the ordinary course of a trade or business that is not a passive investment. The Medicare tax can push ordinary income tax rates up to 43.4% and capital gain and dividends rates to 23.8%.

Even without a reduction from the 34% and 35% corporate rates to, say, 28% as the current administration has proffered, C corporation rates are already 4–5% lower on operating income and another 3.8% lower for the passive FTE owner, thanks to the new Medicare tax.

So since C corporation rates are already lower (and may be dropping another 7-8%), if the business owner was never going to pay a “double taxed” dividend, never going to sell, never going to do any estate planning, and not at all concerned about estate liquidity, logic would dictate strong consideration of reverting to C corporation status.

Fundamentals — taxation during operations and C corporation “double tax”

When an FTE earns income, the individual owners pay tax at individual tax rates on their share of that income. Then, when the cash is distributed out of the company to the owners, there is no tax on the distribution. In contrast, when a C corporation earns income, there is tax at the corporate level and then an additional layer of tax at the individual level when the after-tax earnings are distributed.

For companies that pay dividends, the first fundamental advantage of an FTE over a C corporation is that there is only one level of tax. While the corporate tax rate may be lower than the individual tax rate, the lack of double taxation for FTEs is usually significant enough to overcome the disadvantage of the rate differential, even with corporate rates as low as 28%.

Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the effective federal tax rates that C corporations and FTEs will experience, jointly with their owners, assuming full distribution of all earnings in one case and assuming no distribution of earnings in the other case.

Whether the owner is active or passive, or whether or not corporate rates are decreased, you can see that FTEs have a clear advantage when all earnings are distributed, and C corporations have a clear advantage when no earnings are distributed. More detailed illustrations later in the article explore the gray space in between these two extremes.

Whether the owner is active or passive, or whether or not corporate rates are decreased, you can see that FTEs have a clear advantage when all earnings are distributed, and C corporations have a clear advantage when no earnings are distributed.

Your business’s cash flow projections are probably very complicated and subject to volatility, and where you fall in the spectrum of distributions may be difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, there is no replacement for performing detailed present-value cash flow computations specific to your company’s facts and cash flow needs. Perhaps your company is running very close to its debt covenants and has no cash available for dividends — you may be concluding at this point that it is better to convert from an FTE to a C corporation to unlock the additional 5% to 15% of cash savings on operating taxes — cash you need to reduce debt. That may be the right answer in the short run, but we urge extreme caution. Giving up the advantages of FTE status should be done as a last resort and, as you will see from the following, there can be significant costs to regaining FTE status after giving it up.

The end game — cashing out

We generally recommend organizing privately held businesses as FTEs and urge our clients to at least consider converting privately held C corporations to S corporation form.

The FTE advantage of tax savings during the operating period from large distributions is important — but the advantages when the business is sold are even more compelling.

The tax and economic benefits to owners selling FTEs are significant, notwithstanding the potential decrease in the corporate tax rate. The principal benefits are derived from being able to sell assets, giving the buyer a step-up in basis while still enjoying capital gains treatment on almost all of the proceeds. The details follow.

Most buyers prefer to acquire the assets of a business rather than its stock or ownership units. Acquiring assets allows the buyer to step-up the basis in the assets he or she buys to fair market value. If the buyer pays a premium over the tax basis of the assets, the premium will typically be allocated based on an appraisal. In our experience, the typical result of the appraisal is:

-

the allocated value to both accounts receivable and most of the tangible assets approximates net book value;

-

land and building are based on comparable transactions, with an effort to reduce the allocation of premium to these assets;

-

inventory is marked up about halfway between net book value and its sales value; and

-

the balance is allocated to intangibles with a 15-year tax life.

While the benefit of the buyer’s future tax deductions associated with the step-up in basis is technically the present value of the deductions for all of these assets (and should be carefully calculated in the context of a deal in process), for estimate purposes, treating the step-up as having a 15-year life allows the seller to quickly understand the value to the buyer (since typically the preponderance of the allocation falls to goodwill). The formula for estimating the value is simple: a dollar of step-up results in a present value benefit of 20 cents to the buyer.

This additional value increases the amount the buyer can afford to pay for the company. How much of this value will be captured by the seller in a higher sales price will depend upon negotiation. For the purposes of this analysis, it is assumed that the buyer and seller split the additional value, with 10% of the additional value (roughly one-half) accruing to the benefit of the seller.

This additional value created from the sale of assets rather than the sale of stock can be created whether the business sold is a C corporation or an FTE. However, the tax treatment to the sellers is very different.

Sellers want capital gains treatment on the entirety of the gain on sale and want to pay tax only once.

Properly structured, the assets of S corporations and other FTEs can be sold so that the buyer gets the valuable step-up, while the seller enjoys capital gains taxation on most of the sales proceeds, just as if stock had been sold. (Ordinary income will be recognized to the extent of depreciation recapture and any inventory gain.) Last, the liquidation of the FTE is generally a tax-free event.7

In contrast, the sale of assets by a C corporation will trigger tax at the corporate level at corporate rates (subjecting most of the premium over book value to 34% or 35% rather than individual capital gains rates of 20% or 23.8% tax), followed by a second tax at capital gains rates when the proceeds are distributed to the shareholders. This additional tax burden to the seller will usually exceed the after-tax benefit to the purchaser, eliminating any chance that the sale of a C corporation can be consummated as a sale of assets.

Figure 8 demonstrates this effect. Assume two identical corporations had a tax basis in hard assets of $20 million and a business enterprise value of $100 million in 2003. One company makes an S corporation election in 2003, and the other one continues on as a C corporation. Over the next 10 years, each company earns $50 million in after-tax income. At the beginning of 2013 each company is approached with a buyout offer for $180 million,8 representing a premium over the fair market value of the hard assets (i.e., goodwill) of $110 million. If the seller is willing to structure the transaction as an asset sale, the buyer is willing to split the asset sale premium and would be willing to pay an additional $11 million.9

Figure 8 confirms the previous assertions:

-

The taxes resulting from the sale of assets by a C corporation are so much higher than the taxes on a stock sale that a seller of a C corporation would never agree to an asset sale.

-

The effects of the higher price on the S owner, the lack of double taxation and the higher tax basis from the accumulation of after-tax profits result in significantly more after-tax cash to the seller of an S corporation than the seller of a C corporation.

Passing the business to the next generation

For the family-owned business, estate planning considerations are frequently more important than the income tax considerations when reviewing the question of C corporation versus FTE. Whether the family business is passed on to the next generation or sold and the after-tax proceeds are passed on, the estate planning efficiency of FTEs, particularly for businesses with strong cash flow, can be very powerful. Planning professionals have moved virtually entire FTE businesses down a generation and, in part, two generations without incurring any gift tax and allowing the owner to maintain control.

Most privately held FTE business wealth transfer planning involves using both tax distributions and further distributions in excess of tax distributions to fund the payments required for the older generation owner (G1) who is conveying ownership, usually in trust, to the next generation (G2).

Using an FTE allows these distributions to be free of the second level of “dividend” tax discussed previously, which allows freer cash flow to accomplish the planning goal, without any additional federal tax payments.

The starting point for this planning is the planner and his or her client’s understanding the issues of control and owner lifestyle. Next, the planner needs to examine the cash needs of the owner. This step is critical. We have seen situations where we needed to do “reverse” estate planning because the owner was left with too little cash after a series of wealth transfer transactions. Getting the needed cash to the owner can be accomplished with the sophisticated techniques available today.

There are a variety of transactions commonly used to transfer ownership in privately held FTE businesses to the next generation while allowing the senior generation to continue to control the business and maintain the cash flow needed for his or her lifestyle. Some examples include, but are not limited to, the following techniques:

-

Gift of stock to a grantor retained annuity trust (GRAT)

-

Sale of stock to an intentionally defective grantor trust (IDGT)

-

Stock redemption by the senior generation where the junior generation is already an owner

Case studies

We have illustrated previously the most extreme choices (never pay a dividend or always pay out 100% of earnings as dividends). But most companies operate somewhere in between.

We have created a number of examples in the following text using a 10-year time horizon to examine the gray areas. These examples use a hypothetical company worth $100 million today, with $10 million of annual pretax income. We have assumed that the business grows in value (5%), pretax income grows at the same rate, “free cash flow” to pay tax and dividends is 60% of pretax income, and excess dividends grow at 4%. We have assumed that our owner is active, is in the highest marginal tax bracket and has an estate outside of the business valued at more than $5 million. We have also assumed a 10% premium on the gain if assets are sold (the buyer and seller share the value of the step-up, as discussed previously). After the 10-year holding period, whether the business is passed on or sold, we have assumed the owner passes away, to illustrate the issues of estate tax and estate liquidity that are so vital to the family-owned business. For the purposes of lifetime gifts of nonvoting stock, we have assumed a 20% discount from fair market value (the $100 million to start).

We have also assumed the business is currently an FTE and the owner is considering switching to C corporation status to take advantage of the lower income tax rates. We have examined the results if C corporation rates stay the same (34%) or move to 28%.10 We have assumed the owner has a basis in his stock and each company has a basis in its assets of $20 million in year 1.

Our case analysis has been done with round numbers ($100 million value, $10 million pretax earnings), allowing readers to easily extrapolate based on their own facts. Figure 9 summarizes all of the assumptions.

Taking the business to the grave —Example 1

Many family-owned business owners believe that if they plan on never selling, the right strategy is to hold on to the business and die with it — giving heirs a step-up in basis as of the date of death and allowing them to avoid any subsequent income tax if the business is sold (on appreciation that existed as of the date of death). At a 34% tax rate with 60% free cash flow, the accumulation of cash from dividends is essentially identical between the FTE or the corporate owner. If rates go down to 28%, the owner has $5.6 million more cash accumulated in year 10.

But without any estate planning or a sale, the estate liquidity needs would crush the business and likely result in either a sale or an IRS debt of up to 32% of the business value, which could take 15 years of solid performance to pay off. Unless your business valuation is under the current estate tax exemption ($10 million indexed to inflation for married couples and reaching $10.5 million in 2013), we do not recommend ignoring estate planning during your lifetime.

Management-owned companies that have multiple owners with $10 million exemptions may have a better chance with this strategy and will often use buy-sell insurance to help with the liquidity issue.

Growing the business and selling without estate planning — Example 2

The next example assumes no estate planning and that the business is sold in 10 years. As in the previous example, changing to a C corporation with a 34% tax rate yields no meaningful dividend accumulation advantage, while 28% allows for the same $5.6 million advantage to the C corporation owner as shown in Example 1 (this same advantage exists in all the examples and will not be repeated in the following examples). But even including the dividends, the FTE owner yields about 15% more after-tax cash because:

-

FTEs sell for more because they can sell assets; and

-

lower capital gains tax results from the basis increase from undistributed earnings (the 40% reinvested), and a lower tax rate applies on the capital gains (Medicare tax avoided for active owners) — all slightly offset by some modest ordinary income in the sale (typically some depreciation recapture and gain on inventory for companies with inventory).

Note that these advantages all occur in year 10, and our analysis is based on future value. In examining these decisions, the owners need to consider their own timing for a potential sale, the need for cash in the short run and their own “discount rate,” or weighted average cost of capital (WACC) — typically derived by considering the rate at which the company borrows and the rate of expected return on equity, risk adjusted. This is not a simple analysis, but a necessary one.

Estate planning effects without sale — Example 3

By using a GRAT, owners can use distributions to pay FTE taxes as a way to move value to the next generation. In contrast, C corporation owners cannot use distributions to pay taxes, and must use after-tax dividends to accomplish the same goal. So if our company is distributing 60% of pretax earnings to cover taxes and after-tax wealth building dividends to the owners, only the after-tax dividends can be used in the C corporation context

Moreover, the IRS has typically allowed minority nonvoting stock discounts of 20% or more, reducing the required annuity and allowing more stock to be retained in G2 through the payment of annuities with dividends.

The result is powerful. The 32% liquidity shortfall without planning is eliminated for the FTE in only 10 years. In other words, so much stock is moved to G2 efficiently through the GRAT technique that the cash accumulated by G1 is sufficient to cover all of the estate tax. By contrast, the C owner has a liquidity shortfall of 13–18%, as the after-tax dividends do not allow the ownership to be transferred as quickly to G2. This is true whether C corporation rates are 28% or 34%.

Estate planning followed by sale — Example 4

The sale of a business after careful estate planning turbocharges the results, principally because stock is being given away at a discount, and then it is sold for a control premium. By taking advantage of all the benefits of the sale of the FTE outlined previously (FTE premium, more basis, lower tax rate) and adding on the estate tax savings from moving the sale and dividend proceeds efficiently down a generation, the cash to G2 versus G1 is 34% higher if C corporation rates are reduced to 28% and 45% higher if they stay at 34%. Again, as noted previously, these are future value numbers, and the timing and WACC of the situation will likely temper these results a bit.

Summary

The results summary tells two stories: For those with estates in excess of $10 million for a married couple, the estate tax implications of planning are far greater than the income tax ramifications. While the estate tax implications are sometime in the future, perhaps the distant future, they can take a company from a family.

If estate planning is of primary importance, exit planning is a close second. Tax-efficient exit strategies can significantly enhance the price that a business sells for, as well as the amount of gain reported and the tax rate applied to that gain. All three of these considerations favor the FTE.

Finally, income tax on operations cannot be ignored. It is clear that if C corporation rates go down, there may be significant savings to C corporation owners, especially when dividend distributions are scarce or not possible because of bank covenants. In those instances, the potential increase to cash flow may be influential or even determinative to the decision.

But most people need to factor all of these considerations together, model them out, assume a “discount rate,” present value the analysis and look at the result from a variety of angles to make a decision. In the short run, with rates generally at 34% for C corporation income of less than $10 million, the FTE structure is likely more beneficial. At 28%, the pressure to enjoy the near-term tax savings may overshadow the long-term estate planning and exit advantages. The decision will certainly not be as obvious.

Risk of future tax changes — can we go back?

The years 2010–2012 brought uncertainty and dramatic changes in estate and income tax rules that made planning difficult. In the wake of this uncertainty you may be wondering, “What if I revoke my S election or convert my partnership into a C corporation? Can I ever go back if rates reverse again?”

To convert from S to C is easy. To revert from C to S, the owners must wait five years. To convert from partnership to C is also easy. But you cannot realistically revert from C to partnership without incurring too much tax to make sense of the transaction.

However, if you converted your company from a partnership to a C corporation, you could make an S election without waiting five years. Note that the partnership structure generally has many advantages over the S corporation structure, so giving up partnership status and then reverting to S corporation status is not the same. In short, you can go back, but not easily, and not necessarily immediately.

Conclusion

We are hopeful that tax reform will bring down rates on all business income. Low effective business tax rates encourage investment and business activity, spur job creation and ultimately increase national wealth. We believe the same rates should apply to all businesses, regardless of whether they are organized as C corporations, partnerships, LLCs, S corporations or sole proprietorships. There are compelling economic and business reasons for pass-through tax treatment, and pass-through entities represent an ever-growing share of the economy. If individual rates cannot be lowered along with corporate rates, the authors (and our firm, Grant Thornton LLP) believe that a “business equivalency rate” — enacted either before or as part of tax reform — could ensure that all business income, whether earned in a pass-through or in a traditional corporation, is taxed at an equivalent rate.

But we have lived through eras of wide disparity in the tax rates on C corporations versus FTEs. We encourage business owners to start or re-invigorate the process of long-term tax planning, taking into account growth strategies, financing strategies, and multistate and multinational considerations, and to pay close attention to ownership succession, be it through gift, inheritance, sale, merger or otherwise. The recent changes in the tax rules require that ownership be vigilant. Simply put, it is an owner’s fiduciary duty.

Footnotes

1 In reaction to 70% rates on ordinary income, the Tax Reform Act of 1969 introduced the “maxi-tax,” limiting the tax rate on personal service income to 50%. This period from the 1970s to 1986 allowed for heavily leveraged investments in real estate and other assets that allowed sophisticated taxpayers to lower their individual taxes significantly, ushering in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which all but eliminated these tax-motivated investments but lowered tax rates significantly in return.

2 See Figure 1. Individual rates in 1981 were 22% higher than corporate rates: 70% versus 48%.

3 PHC tax was levied on closely held C corporations that had more than 60% of their income from investments and other specific sources. The historic tax rate was an additional 15% tax. Similar to the “passive income tax” for S corporations, the tax is aimed at closely held C corporations that have sold the business, but have not distributed the cash or liquidated to avoid the second level of tax engendered. Today, the family limited partnership has essentially replaced the PHC as the entity of choice for holding investment assets. The accumulated earnings tax is levied on C corporations that accumulate too much cash and do not make dividend distributions. The tax calculation allowed for consideration for working capital and capital expansion, but unnecessary accumulations were taxed at 15%. Few ever actually paid the tax, and the move to an S corporation or LLC eliminated the issue for the closely held business owner. Closely held C corporation owners used to avoid double taxation by declaring very large bonuses at year-end to eliminate the corporate tax. The IRS would challenge these bonuses and tax them as dividends. Again, S corporations and LLCs eliminate the need for this maneuver, as any bonus simply lowers the FTE’s net income, and the same amount of income is taxed to the owners.

4 C corporations with significant earnings and profits offshore or with owners that cannot conform to the S corporation rules are two special circumstances occasionally encountered.

5 The FTE typically sells assets or engages in a “deemed” asset sale, typically allowing capital gains for all but a small portion of the total gain and allowing the buyer a “step-up” in asset value that is depreciable, generally over 15 years. This step-up creates value of approximately 20% of the gain on a present-value basis. The extra benefit allows the buyer to pay more in purchase price to the seller or keep all or some of the benefit for himself or herself. In any case, the value is “extra” value not available in the sale of a C corporation.

6 There are a series of graduated rate brackets on income of less than $335,000 for C corporations and $450,000 for individuals, and a 38% bracket on C corporation income from $15 million to $18.33 million. For more than $18.33 million, C corporations pay a flat 35% rate on all taxable income.

7 S corporations that were previously C corporations will often have income upon liquidation approximating the “retained earnings” (technically the earnings and profits, or E&P) of the company on the date it made its S election. S corporations that were previously C corporations may need to perform an analysis of their E&P to figure out the second layer of tax on liquidation.

8 The 2013 value of $180 million represents the 2003 value of $100 million, grown over 10 years at 5% per annum plus a 10% control premium.

9 Note that the FTE column of the table represents either a sale of S corporation stock with a Section 338(h)(10) election (i.e., a stock sale treated as an asset sale) or a straight sale of assets. We have not illustrated a sale of S corporation stock without a Section 338(h)(10) election because, given the advantages to the buyer and seller of making the election, stock sales of S corporations without a 338(h)(10) election rarely occur in practice.

10 Note C corporations with earnings of less than $10 million are now subject to 34% tax. Our analysis compares results at both the 28% (assuming C corporation rate reductions) and 34% levels. Corporations in the 35% bracket would need to adjust these results slightly.

11 A conversion from a C corporation to a partnership (or an LLC, taxed as a partnership) is generally taxed as a taxable liquidation, followed by a tax-free formation of a partnership. In such a transaction, all of the gain that is built up within the C corporation is triggered and creates two layers of tax. That is why this transaction is almost always avoided.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.