Finnegan attorneys Lionel Lavenue, Benjamin Cassady, Robert Fernandes, and Kayvon Ghayoumi explain the reasons behind the current direction of attorney fee awards in patent cases.

The Supreme Court's 2014 Octane Fitness decision1 lowered the bar for awarding attorney fees under Section 285 of the Patent Act, 35 U.S.C.A. § 285. In the years following the decision, parties filed motions for attorney fees under Section 285 more frequently - even as the overall number of patent cases decreased.2

We examined how decisions from the last quarter of 2020 compare to pre- and post-Octane trends, in addition to trends across all types of sanctions in patent cases awarded under all sources of authority. This includes Rule 11 sanctions, sanctions awarded pursuant to courts' inherent authority, 28 U.S.C.A. § 1927 fees, and discovery sanctions.

Ultimately, we found that Octane Fitness has not considerably changed the rate that courts grant sanctions and motions for attorney fees, a trend that has remained consistent through the last quarter of 2020.

Trends in § 285 awards

Section 285 allows courts to grant attorney fees to the prevailing party in exceptional patent cases. Before Octane Fitness, Federal Circuit precedent limited the application of Section 285 to objectively baseless cases that were brought in subjective bad faith or to cases that involved litigation misconduct of an independently sanctionable magnitude.

In Octane Fitness, the Supreme Court explained that the Federal Circuit's standard was too strict, as it rendered § 285 largely superfluous. According to the Supreme Court, attorney fees were already available when the losing party acted in bad faith, vexatiously, wantonly or for oppressive reasons, e.g., under courts' inherent authority or other statutes.

Carving out § 285 from other fee-shifting mechanisms, the high court determined that § 285 fees may be awarded against a party that acts in an objectively baseless way or in subjective bad faith.

Likewise, the Supreme Court permitted courts to award fees in any case in which a party's unreasonable conduct is exceptional and "stands out" - regardless of whether the conduct is independently sanctionable. Finally, the Supreme Court rejected the Federal Circuit's clear and convincing standard and opted for the ordinary preponderance of the evidence standard.

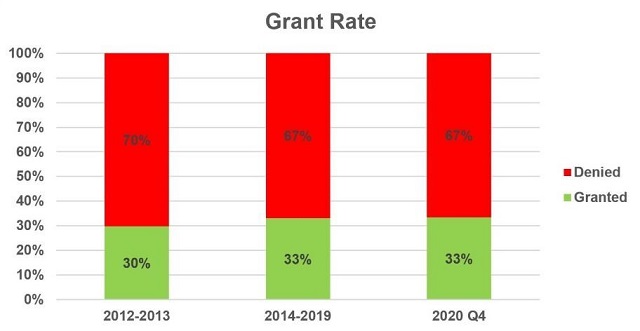

Following Octane, from 2015 to 2019, patent case filings declined3 while the number of motions for attorney fees under § 285 filed each year increased compared to pre-Octane levels.4 Among motions for fees under § 285, though, pre- and post-Octane grant rates do not differ substantially.

In the years immediately preceding Octane, courts granted (in part or in full) approximately 30% of motions for fees under § 285.5 Grant rates varied in the years following Octane but have leveled off to about 33%.6

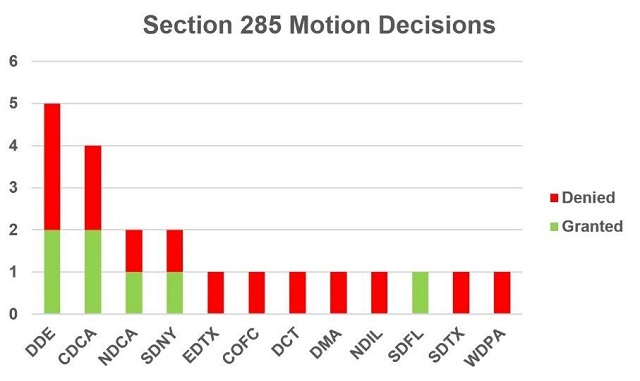

The data for this quarter looks strikingly similar. In the last quarter of 2020, district courts granted 33% of § 285 motions (excluding decisions calculating fees or requesting additional briefing). As with other data in the years following Octane, in the last quarter of 2020, the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware decided more § 285 motions than any other court.

It granted two motions and denied three. The Central District of California decided on four § 285 motions. It granted two and denied two. The Northern District of California and the Eastern District of Texas, both of which historically handled a large share of § 285 motions, only adjudicated two and one respectively (again, not including decisions calculating fees or requesting additional briefing).

In total, courts adjudicated 21 motions for attorney fees in the last quarter of 2020. This is a slight downturn from the over one hundred § 285 motions decided each year following Octane. The downturn is particularly notable in light of an uptick in patent suit filings this year, which saw more patent cases than any year since 2015.

Trends in sanctions and fee shifting under other mechanisms

But § 285 is not the only avenue for obtaining attorney fees. Litigants can also turn to 28 U.S.C.A. § 1927, Rule 11 or a court's inherent authority. This may happen, for example, when the party seeking fees is not technically the "prevailing" party under § 285, which is only available to the prevailing party (e.g., in some circumstances where the plaintiff voluntarily dismisses its complaint).7

Section 1927 gives courts discretion to award sanctions against an attorney that unreasonably and vexatiously multiplies proceedings. This can include any excess costs, expenses and attorney fees caused by the conduct.

Rule 11 allows for both monetary and non-monetary sanctions, including attorney fees, that can be assessed against the opposing party or attorney. To move for sanctions under Rule 11, though, a litigant must typically follow proper procedure.

The litigant must serve a Rule 11 notice on opposing counsel and give the party 21 days to withdraw the offending filing. Notice must also be given at least 21 days before resolution of the case or offending filing, which further limits Rule 11's availability.

When Rule 11 and § 285 are not available, a court may still award sanctions, including attorney fees, under its inherent authority. To impose sanctions of attorneys under inherent authority, a court generally must find that a party acted in bad faith - a higher bar than Rule 11's objective reasonableness standard (though non-fee shifting sanctions under a court's inherent authority may not require a finding of bad faith).8

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure also provide for sanctions for discovery-related misconduct. Rule 30, for example, allows courts to sanction parties that impede, delay or frustrate deposition taking. Rule 37 allows for a broad range of sanctions that depend on the type of discovery-related misconduct.

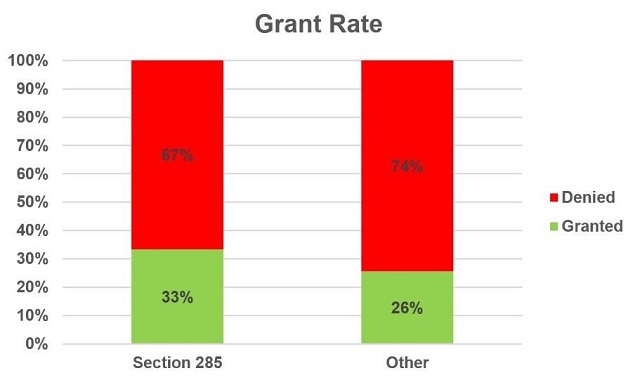

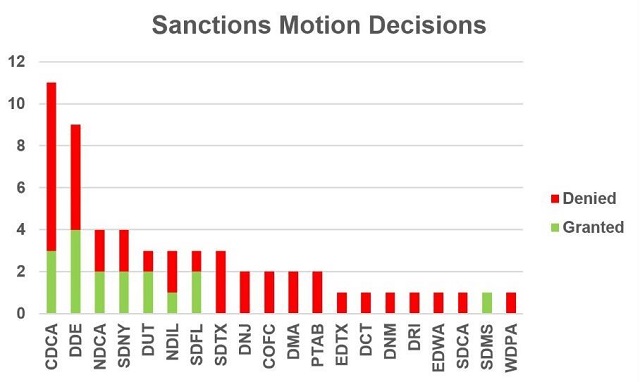

The numbers reflect the higher bars and procedural impediments associated with non-§ 285 motions. In the last quarter of 2020, courts only granted 26% of non-§ 285 sanctions motions. Courts adjudicated 39 non-§ 285 sanctions motions, which is almost double the number of § 285 motions decisions.

Over half of the non-§ 285 motions were for discovery-related sanctions under Rules 30 and 37, though. Grant rates between discovery related sanctions motions and other sanctions motions were comparable.

Examples of conduct triggering fee awards

Realtime Adaptive Streaming LLC. v. Netflix Inc.9 provides a good example of conduct that leads to fee shifting under § 285. In November of 2017, Realtime sued Netflix for patent infringement in Delaware.

Netflix filed a motion to dismiss, arguing in part that four of the six asserted patents were directed to patent ineligible subject matter. The magistrate judge recommended granting Netflix's motion for invalidity.

While the magistrate judge's report was pending before the District Court, that same District Court judge invalidated five related patents owned and asserted by Realtime in a parallel case. Shortly thereafter, Realtime filed a motion to dismiss their case against Netflix without prejudice.

On the same day Realtime moved for dismissal in Delaware, the company filed a pair of cases in the Central District of California, asserting in part the same four patents. Netflix moved to transfer the California cases to Delaware and for an award of attorney fees. After both Realtime and Netflix spent significant time briefing the motions to transfer, Realtime moved to voluntarily dismiss both cases.

The court still considered Netflix's motion for attorney fees under §285. The court first considered whether Netflix was the prevailing party. Ordinarily, though not always, a voluntary dismissal without prejudice does not create a prevailing party, since the underlying matter is not adjudicated on the merits, and the plaintiff remains free to refile at any time.

However, under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a second voluntary dismissal of the same claim is treated as "an adjudication on the merits."10 Considering the issue as a matter of first impression for the Central District of California, the court concluded that Netflix qualified as the prevailing party for the purposes of sanctions.

The court also found the case exceptional because of Realtime's impermissible forum shopping. Realtime initially opposed Netflix's attempt to transfer the Delaware case to California, only to later drop the Delaware case and refile in California.

The court noted that Realtime only dropped the Delaware litigation when it became apparent that the court in Delaware would not be issuing a favorable ruling, and then immediately refiled a functionally identical lawsuit in a forum it initially opposed a transfer to. The circumstances suggest Realtime was engaged in impermissible forum-shopping and supported a finding of exceptionality.

Ultimately, the court awarded Netflix $409,402.50 in attorney fees and costs it incurred defending the California litigation.

Cedar Lane Technologies Inc., v. Blackmagic Design Inc.11 provides an example of the conduct that leads to Rule 11 sanctions against attorneys. Cedar Lane was represented by two attorneys, Isaac Rabicoff and Kirk Anderson.

Anderson initially served as local and lead counsel, while the early case filings indicated that Rabicoff's "Pro Hac Vice admission [was] to be filed." Cedar Lane filed two amended complaints without first obtaining permission under Rule 15 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

When Blackmagic moved to strike the improper amended complaints, Cedar Lane responded that Rule 15 allowed a filing of amended complaints as a right whenever a motion to dismiss was filed - an argument the court called "objectively frivolous."

Rabicoff and Anderson also failed to attend the hearing for Blackmagic's motion to strike. When the court ordered the pair to show cause as to why they should not be sanctioned, Rabicoff blamed his failure to appear on the court's lack of notice, and Anderson admitted to not having read Cedar Lane's opposition brief to Blackmagic's motion to strike before signing. Finally, at the hearing on the motion to show cause, the attorneys admitted Rabicoff had been serving as lead counsel for the duration of the lawsuit.

The court concluded this case was likely not the first time Rabicoff served as lead counsel while skirting pro hac vice requirements. After requiring Rabicoff to supply the court with his litigation history in the Northern District of California over the previous five years, the court found 29 cases where Rabicoff appeared as lead counsel but did not seek pro hac vice admission or pay the proper fees for applying for admission.

Ultimately, the court sanctioned both attorneys under Rule 11 for frivolous arguments, and further sanctioned Rabicoff under its inherent power for making misrepresentations to the court. Rabicoff was further referred to the Northern District's Standing Committee on Professional Conduct for possible violations of Civil Local Rule 11-3, which requires attorneys regularly appearing before the Northern District of California to be admitted to practice in the district and not appear pro hac vice.

SIMO Holdings Inc. v. Hong Kong Ucloudlink Network Technology Ltd. and Ucloudlink (America) Ltd.12 involved discovery sanctions. SIMO was sanctioned for disclosing four confidential documents subject to a protective order to one its subsidiaries.

The disclosure appeared to have happened as part of discussions between the legal teams for SIMO and its subsidiary over how to maintain consistency in parallel actions in the United States and China. However, the court maintained that the limitation to "this action" in the protective order meant "this action" and did not include related cases. The court sanctioned SIMO to the tune of $40,000.

Conclusion: Post-Octane trends in fee shifting remain constant

The lower bar for sanctions under § 285 established by Octane Fitness has not appreciably changed the rate at which courts sanction parties or their counsel. Motions for sanction or attorney fees continue to be granted at around a 30% rate (under § 285 and otherwise). And while the frequency of § 285-motions increased following Octane Fitness, this trend appears to have cooled off in the fourth quarter of 2020.

Footnotes

1 Octane Fitness LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness Inc., 572 U.S. 545 (2014).

2 Dani Kass, Fast Courts, Big Funders Kept Patent Suits Flowing In 2020, Law360 (Mar. 10, 2021), https://bit.ly/3mxGfQ6.

3 Id.

4 Ryan Davis, Fee Awards Loom Large in Patent Law 3 Years After Octane, Law360 (Apr. 27, 2017), https://bit.ly/3wGJSIj.

5 Id.

6 Christine Armellino & Robert Frederickson, Examining Octane Fitness Five Years On, IP Watchdog (Apr. 29, 2019), https://bit.ly/39YWG2Z.

7 Lionel M. Lavenue et. al., Evolving Case Law Elucidates Atty Fees for Patent Litigants, Finnegan (July 17, 2020), https://bit.ly/3uByOKz.

8 Chambers v. NASCO Inc., 501 U.S. 32 (1991).

9 Realtime Adaptive Streaming LLC v. Netflix Inc., No. 19-cv-6361, (C.D. Cal. Nov. 23, 2020).

10 Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(1)(B).

11 Cedar Lane Techs. Inc. v. Blackmagic Design Inc., No. 20-cv-1302, (N.D. Cal. Nov. 19, 2020).

Originally published by Westlaw Today

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.