The Establishment of the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court and What It Means for International Business

INTRODUCTION

The creation of a new European Unified Patent Court ("UPC") and a new patent with unitary effect ("Unitary Patent"), in which almost all member states of the European Union participate,1 is the most important change in the European patent system since the European Patent Convention came into effect in October 1977. It paves the way for a unified approach to patents in Europe and will fundamentally change the international patent litigation landscape.

The UPC is intended to improve the existing system in which patents granted by the European Patent Office ("EPO") can only be enforced or revoked in national courts. This often results in two or more parallel actions in different countries. There are also significant differences between the approach and procedures of various national courts and this has often led to inconsistent decisions.

The new system is expected to come into force in 2017. The procedural rules were adopted by the Preparatory Committee on 19 October 2015 and these are now in a near-final form, allowing companies to properly plan for the new system. In this Jones Day White Paper, we look at the key features of the new system, as now finalised, and the implications for business.

THE LARGEST PATENT COURT IN THE WORLD

The UPC will be the largest (by GDP of its jurisdiction) patent litigation forum in the world, dealing with patent disputes across Europe. It will provide a unified system for the enforcement of patent rights across Europe by replacing the existing patchwork of different national patent litigation regimes.2 The court will eventually have exclusive jurisdiction not only over the new Unitary Patents but also over standard European patents which have not been "opted out" of the system. This means any business operating in Europe could be subject to proceedings before the UPC.

Court Structure

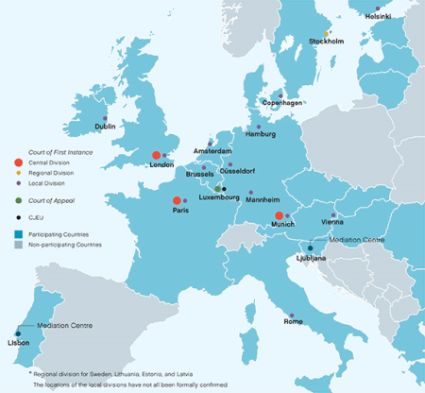

The basic structure of the UPC has been agreed—the court will consist of a Court of First Instance, a Court of Appeal and a Court Registry. The Court of First Instance will have local divisions (set up in individual member states), regional divisions (which can be set up jointly by two or more member states that do not want to set up their own local division)3 and a central division. The seat of the central division will be in Paris with sections in London (focusing on chemistry cases, including pharmaceuticals) and Munich (focusing on mechanical engineering cases). The Court of Appeal and the Court Registry will be based in Luxembourg.

In addition, a patent mediation and arbitration centre will be established with seats in Ljubljana and Lisbon, and a training framework for judges will be set up in Budapest.

The Judges

The proceedings before the local and regional divisions will be heard before a panel of three judges. At local divisions with a history of more than 50 cases per year, this panel will consist of two judges who are nationals of that member state and one who is a national from another member state. At local divisions with a history of fewer than 50 cases per year, the composition of the panel will be the other way around. For regional divisions, the panel will comprise two legally qualified judges who are nationals of the member states participating in that regional division and one legally qualified judge who is a national of a different member state.

This system is designed to ensure impartiality and a degree of consistency in the court's decision-making. Nevertheless, we expect that at least in the early days of the UPC, the countries that presently have strong patent regimes will contribute disproportionately to the pool of judges. These experienced judges will sit alongside judges from other jurisdictions, with the result that experience will be shared and developed over time.

Another important feature of the UPC is that there will be both legally qualified judges and technically qualified judges. Legally qualified judges will need to have the qualifications required for appointment to judicial offices in their home state. Technically qualified judges must have a university degree and proven expertise in a field of technology as well as proven knowledge of civil law and procedure relevant to patent litigation. The judicial panels of the central division—which will be the primary forum in which patent revocation actions will be heard—will always be composed of two legally qualified judges and one technically qualified judge. Where a local/regional division decides to hear a revocation claim at the same time as an infringement claim, the panel will appoint a technical judge as an additional judge and may also do so whenever it believes it appropriate. The presence of technically qualified judges on the panel is likely to mean that the court will be less reliant on the parties' own experts. It may also lead the court to take on a more inquisitorial approach to technical evidence and a more "hands on" approach in directing any experimental evidence.

The process for the selection and training of judges is already underway in Budapest. The Advisory Committee of the UPC, which comprises patent experts from across Europe, will be responsible for making the judicial appointments.

Opting Out and Transitional Period

There will be a transitional period for the UPC of at least seven years (which may be extended by a further seven years) where infringement and validity actions on standard European patents may still be brought before national courts or other national competent authorities. This means that during this transitional period, litigants will have a choice of forum for instituting patent proceedings on these patents.

In addition, during the transitional period, an owner of a standard European patent or a related SPC or European patent application will be able to opt out of the jurisdiction of the UPC on a patent-by-patent basis, provided that no action has been brought before the UPC in the interim. On opt out, all national designations of the European patent can be litigated only in the national courts. Once a patent has been opted out of the UPC's jurisdiction, it can be opted back in at any time before the end of the transitional period, providing no action has already been brought before a national court. Effectively, this would allow patentees to remove patents from the UPC system during the initial start phase and have them re-join the system once the system is more established.

A NEW APPROACH TO EUROPEAN PATENT LITIGATION

There are significant procedural differences in how patent litigation is presently conducted in different European member states. In common law countries such as the UK, the proceedings tend to be more detailed with longer trials and greater focus on expert evidence and oral witness testimony. On the other hand, in civil law countries such as Germany, the proceedings tend to be briefer with more focus on written procedure and short trials. The draft Rules of Procedure of the Unified Patent Court ("UPC Rules")4 seek to bring these various approaches together, and the result is a mixed procedural framework that includes elements from each of these different legal systems.

In this part, we look at a number of the features of the UPC Rules that are likely to have significant strategic implications for litigants.

Potential Bifurcation of Infringement and Validity Proceedings

Infringement and validity actions are presently tried in separate courts in certain member states, such as Germany and Austria (the process is known as "bifurcation"). Most other European countries, however, have an integrated system where both infringement and validity issues are tried together before the same court. The UPC will retain the basic principle of bifurcation but will also give the judges a wide discretion to try validity and infringement issues together in appropriate cases. This hybrid system is designed to take advantage of the benefits of bifurcation—i.e. speedily reaching a decision on infringement—whilst at the same time avoiding parallel actions where validity is put in issue.

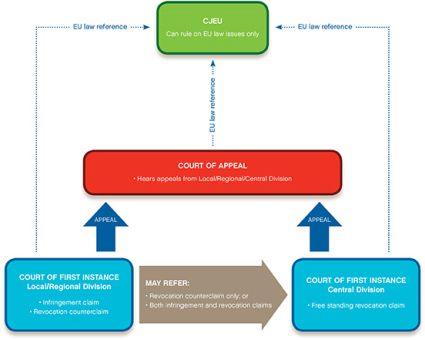

The starting position is that all actions for infringement and applications for provisional remedies (i.e. interim relief) must be brought before a local or regional division in which infringement is occurring or in which the defendant is resident. In the absence of any local or regional division in the member state where infringement is occurring, proceedings may be brought before the central division. On the other hand, all free-standing revocation actions and declarations for non-infringement must be brought before the central division.

If a revocation counterclaim is filed in response to a pending infringement action, the local or regional division has various options as to how to proceed:

- It can proceed with both claims, after requesting the President to allocate a judge with relevant technical qualifications to the panel;

- It can refer the counterclaim for revocation to the central division and suspend or proceed with the infringement action itself; or

- It can refer the whole case to the central division, with the consent of the parties.

The local/regional court has a similar choice if an infringement action is brought when there is a pre-existing validity challenge at the central division.

The possibility for bifurcation was one of the most controversial issues in the negotiations for the UPC, and there is still considerable uncertainty as to how the court will approach it in practice. Indeed, commentators have noted that if different divisions of the court adopt different approaches, this may lead to forum shopping. There are, however, a number of reasons why the impact of bifurcation may be less significant than initially thought.

First, as discussed further below, the UPC Rules place significant emphasis on written procedure and require the parties to set out their case in detail (including expert witness evidence) early on in the proceedings. This means that at the time of exercising their discretion, the local or regional court judges will have considered detailed (and fairly well-advanced) arguments on validity and will have formed at least a preliminary view on the merits. In these circumstances, the local or regional court judges may be in a better position to hear the case than referring the matter to the central division judges who must look at the issues afresh.

Second, even where a decision is taken to bifurcate, the UPC procedural rules mandate that the infringement case must be stayed where there is a "high likelihood" that the relevant claims of the patent(s) will be held invalid. There is, however, no guidance as yet as to how "high likelihood" is to be judged and whether it will be judged differently in different divisions. If the standard is not set too high, it will make it more difficult for unprincipled patentees to use the tactic of issuing infringement cases to extract substantial royalties based on low-quality or invalid patents.

Finally, in bifurcated proceedings, the UPC Rules require the central division to accelerate the revocation action referred to it by the regional or local division in cases where the infringement action has not been stayed. This should reduce any tactical advantage that a patentee may otherwise achieve in running parallel infringement and revocation proceedings in different courts. This may ultimately lead to the parties agreeing in many cases to have both infringement and revocation heard together before the same panel, and the court may well consider this as an important consideration in exercising their discretion.

An Emphasis on Written Procedure

The UPC Rules provide for a three-stage procedure for cases: an initial written procedure, followed by an interim procedure and finally an oral procedure. The overall aim is that most cases will proceed to an oral hearing within a year.

The written procedure is given particular importance under the UPC Rules, and all written pleadings are required to provide extensive amounts of details on the nature of the case. The Statement of Claim for infringement cases must, for instance, not only identify the patent claims alleged to be infringed but also provide reasons why the facts relied on constitute an infringement of the patent claims, including arguments of law and evidence relied on and, where appropriate, an explanation of the proposed claim interpretation. Similarly, a party seeking to revoke a patent must identify at the outset any evidence it relies on in support, which we expect would need to include at least a summary of the arguments regarding novelty/inventive step in relation to identified prior art and what is alleged to form part of the common general knowledge. This detailed approach to initiating documents is more similar to German pleadings than UK pleadings (which are usually limited to just the bare allegations). In effect, this means that the UPC Rules seek to frontload the arguments and facts of the case towards the start of the proceedings. This will force the parties to "nail their colours to the mast" at the outset which could lead to early resolution of disputes or at least a significant narrowing of issues that will need to be tried at the oral hearing.

The UPC Rules also provide that the court Registry will take an active approach to the parties' written pleadings. In particular, the Registry will review them as soon as practicable after they are lodged and will ensure that they comply with all the requirements. If they do not, the Registry will ask the relevant party to correct any deficiencies it has identified. This active case management by the court may lead to a reduction in the number of procedural disputes between the parties and highlight deficiencies in the parties' positions early on.

No Automatic Discovery

The UPC Rules do not provide for any automatic disclosure process. The court may, however, order a party making a statement of fact to produce evidence that lies in the control of that party. The UPC Rules also contain a number of provisions allowing a party to request the court to order the other party to produce evidence, preserve evidence and inspect products, devices, methods or premises.

The absence of an automatic disclosure means that parties will need to take a pro-active approach to obtaining documents and other information from the other side. This will be particularly important, for instance, in cases involving process patents where the patentee may not be able to form a view on infringement without provision of information from the alleged infringer. It is unclear at this stage whether the UPC will adopt a similar system to the UK where the alleged infringer can submit a product and process description in lieu of providing disclosure of documents, although this is certainly within the scope of what the court can order. Alternatively, the UPC Rules provide for "dawn raids" on the defendant's premises to collect evidence, a procedure already enjoying high popularity e.g. before German courts.

It is also worth noting that the rules of providing evidence by experiments borrow from both the UK and German practice: for example, in line with the practice in Germany, the parties themselves may conduct and file experiments as evidence. However, experiments may also be ordered by the court, as is common in UK litigation practice, although the request for experiments needs to be lodged as soon as practicable in the written procedure or the interim procedure. In either scenario, parties will therefore need to think early on how experiments fit into their case.

Applying for Interim Relief

The UPC will be able to grant a number of provisional measures pending the outcome of a case including injunctions, seizure or delivery up of suspected infringing goods, and interim costs awards. These remedies are of particular importance in pharmaceutical patent cases because the entry of a generic medicinal product usually leads to a permanent price reduction for the originator drug, even where the originator company's patent is ultimately found to be valid and infringed. In recognition of this, the courts in many member states (in particular the UK and Germany) have tended to side with originator companies in granting interim relief blocking entry to generic companies that have simply sought to launch products at risk without first "clearing the way".

It is presently unclear whether the UPC will follow a similar approach. The UPC Rules include only a very general principle that in exercising its discretion, the court shall weigh up the parties' interests and, in particular, consider the potential harm which the parties would respectively suffer as a result of the grant, or refusal, of an injunction. However, it is unclear the extent to which the court will take into account the underlying merits of the infringement and validity issues; in fact, the rules require the applicant only to provide a "concise description" regarding the case on the merits. There is also discretion for the court to proceed without a hearing (i.e. grant relief on an ex parte basis) where the urgency of the action demands it or where the patent has been upheld previously in EPO opposition or some other court proceedings.

It is also uncertain how and to what extent the UPC will take account of the differences in pharmaceutical regulatory and reimbursement regimes in different member states in exercising its discretion on provisional measures. It may be necessary in certain cases to fashion injunctive relief to apply differently in the various member states.

We expect that there will be further guidance on these issues closer to the commencement of the UPC. Given the tactical value of preliminary injunctions in the pharmaceutical space (particularly where it concerns access to the entire European market), it will be essential for the court to have in place a predictable and consistent approach to provisional measures.

Court Fees and Cost Recovery

Court fees have not yet been decided and are presently subject to an ongoing consultation by the Preparatory Committee. It is currently proposed that the court fees will comprise a fixed fee set and an additional "value based fee" which will be calculated according to an objective assessment of the value of the case. In relation to the latter, the current proposal is for a maximum amount of €220,000 for a case valued over €30 million. While from a UK perspective, this would seem unnecessarily high, particularly as most major pharmaceutical and consumer electronics cases will easily exceed this threshold, the court fees would still be less than the current court fees in litigation in Germany.

There are also proposed caps on the costs that will be recoverable by a winning party (which includes lawyers' fees, experts' fees and costs associated with experiments, translations and all other disbursements). The caps that are currently proposed seem fairly low compared to the usual costs for patent litigation in the UK (for instance, for cases that are valued up to €30 million, the costs cap is €1 million). If these caps are adopted, it would mean that for a typical UK-based action, the costs recovery is likely to be around 50 percent of the actual costs incurred. At the same time, however, these recoverable fees under the UPC system would still be significantly higher than the fees that are currently recoverable in other jurisdictions, such as Germany (there, recoverable fees for cases that are valued up to €30 million are capped at around €450,000).

It should be noted, however, that even if the fees in the UPC system exceed the fees that would be currently incurred in one jurisdiction, the potential savings by having to conduct only one litigation instead of multiple litigations will still be significant.

THE UNITARY PATENT

The Unitary Patent will provide uniform protection with effect in all of the 25 participating member states. It will be a third route to patent protection in Europe, alongside national patents and the standard European patents with national designations that are currently issued by the EPO.

Crucially, the Unitary Patent will not replace the existing European patent system but rather exist alongside it. It will be possible for applicants to choose between combinations of national patents, European Patents and Unitary Patents. This allows applicants to choose the option best suited to their protection needs. In this respect, it needs to be considered that Unitary Patents will need to be litigated exclusively before the UPC. It will not be possible to opt out any Unitary Patents from the UPC system.

The Unitary Patent will be granted by the EPO using the existing patent application procedures. On grant, applicants will have three options to choose from:

- Do nothing further and proceed with patent validation in the designated countries. This would then be a European Patent and not a Unitary Patent;

- Request that the patent is granted as a Unitary Patent covering the contracting EU member states. Such request must be filed within a month of grant and in accordance with the relevant translation requirements. Importantly, such Unitary Patent will only cover member states that have ratified the agreement on the UPC at the time of the request; or

- Elect to have a Unitary Patent and at the same time validate in countries that do not participate in the Unitary Patent Package. In this case, any "national" elements outside the "unitary effect" zone will co-exist with the Unitary Patent.

The Unitary Patent will be subject to the payment of a single set of renewal fees which will manage the scheme centrally. According to the "True top 4" schedule, these fees will correspond to the sum total of the renewal fees paid for the four countries in which standard European patents are most frequently validated (namely, Germany, France, the UK and the Netherlands). According to this schedule, the total renewal costs for a Unitary Patent for the life span of 20 years will be less than €36,000 as opposed to about €160,000 for the respective 25 national patents. Thus, cost savings will be significant for patents widely validated across Europe. At the same time, additional costs associated with national patents existing alongside the Unitary Patent will somewhat mitigate the overall cost-saving effect.

Most of the savings will be realized within the first years of patent life. However, given that the present EPO's average pendency to grant is about five years, in practice the difference in renewal fees for a Unitary Patent and national fees in the early years will not have a significant impact on cost savings.

Another relevant aspect is that in the current system, the patent proprietor can manage renewal costs by successively dropping those states where costs exceed perceived benefits. Consequently, it is commonplace for patents to be widely validated at grant but shrink geographically to a small number of high GDP or strategically important states over time. In the new system, it will not be possible to drop off individual states from a Unitary Patent and thus reduce renewal costs.

The other, positive side of a unique renewal fee is that those countries which were previously not considered for validation due to their lesser significance will also be covered at a cost of one renewal fee. This will enlarge the geographical scope of a patent as a bonus effect.

Given the above considerations, applicants in various technological fields with varying validation schemes might run different filing strategies.

For example, where protection is required only in a small number of countries, filing national patent applications might be a valid option that would allow patentees to avoid excessive maintenance costs, as well as the uncertainty associated with the new system.

Alternatively, when going for a European application, the decision may be taken to stay within the existing system and opt out the European applications and patents from the UPC. This step must be taken in a timely way before the new system comes into force to ensure that the patent is not immediately attacked by an invalidity claim at the UPC, since an opt-out would then no longer be possible.

It will also be possible to apply a diversifying strategy: patents which are elected to become Unitary Patents may be backed up by European Patents of similar scope which are opted out of the new system. To this end, one might consider filing divisional applications with somewhat different scopes that would enter different routes as patents.

All strategies have their distinct advantages and disadvantages. When making a decision, however, it becomes more important than ever to not only consider the prosecution side, but also to specifically identify the potential enforcement scenarios that may emerge in the future and how the applicant wants to position itself in litigious situations.

NEXT STEPS AND OUTLOOK

The UPC will begin to operate three months after 13 member states including the UK, France and Germany have ratified the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court ("UPC Agreement"). To date, the agreement has been ratified by eight member states, although this does not include either Germany or the UK. The Unitary Patent will be available once the UPC Agreement enters into force. It is currently expected that the UPC and the Unitary Patent will be operational around mid-2017.

To oversee the establishment of the UPC, the signatory states of the UPC Agreement have set up a Preparatory Committee. The Committee has been tasked with setting up the necessary legal framework for the UPC including the procedural rules, the financial aspects of the court, IT facilities and HR infrastructure. It is also overseeing the training of judges. With all these efforts currently underway, the current expectation for the system to come into effect is also around mid-2017.

While there seems to be some reluctance among infringement plaintiffs to be the first before court to shape the case law, there may be an initial surge of case law on validity: it seems likely that at the moment of the launch of the system, a multitude of strategic revocation actions may be filed against such European patents that have not been "opted out" of the system. This move to "force in" would allow parties to challenge validity across Europe in a single proceeding, even if the standard opposition period for these patents has long lapsed.

Depending on the perspective, the new system will thus bring both risk and opportunity. In any event, this dramatic change in the patent landscape will happen and cannot be ignored. It is likely that those who will benefit most are those who are prepared and who develop their strategies early.

Footnotes

[1] Note that Spain, Poland and Croatia are not presently participating.

[2] The new system will not apply to national patents, which will continue to be enforced on a country-by-country basis. These currently comprise a small minority of patents in Europe.

[3] The only regional division that has been announced so far is the joint Nordic–Baltic regional division seated in Stockholm and comprising Sweden, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

[4] The rules are presently in their 18th draft.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.