The IPR program in general has been wildly successful in its intended purpose of providing a lower-cost alternative to patent litigation, and the number of filings has remained relatively steady (though there were somewhat less in 2019 and 2020 as compared to previous years). The same is not true of IPRs filed in the TC 1600 space.

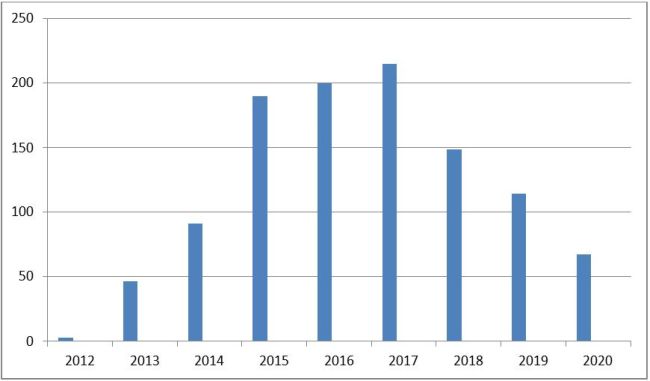

This chart shows IPR petition filings in the TC 1600 space by fiscal year:

Petitions rose steadily to an all-time high in 2017, and then have continued to drop off dramatically, with 2020 having only 67 petitions-barely more than in the first full year of the program's existence. Notably, PGRs in the TC 1600 space have fallen off slightly as well, though not as dramatically. These statistics come from Oblon's TC 1600 Post Grant Library, and closely track the PTO's own statistics illustrating this issue.

So, why the decline? I have considered several issues, none of which seem to explain the drop-off.

For example, most patents challenged in IPRs are concurrently involved in district court litigation, and the number of district court litigations remains relatively steady. In fact, Hatch-Waxman suits have increased slightly even in the years where TC 1600 IPRs dipped.

Patents challenged in the TC 1600 space have a slightly higher chance of surviving IPR than patents from other technology areas, likely due to the inherent unpredictability of these arts, but not so much as to render an IPR proceeding futile.

As can be seen in the Oblon TC 1600 Post Grant Library, many of these challenged patents are associated with orange-book listed commercial products. Thus, it may be expected that secondary considerations can be relied on to rebut an obviousness challenge in an IPR. But, commercial success has rarely been successful in that context, for reasons explained in my previous blog.

IPR filing fees have gone up over the years, but haven't seem to deter filings in other area, so this is not likely a significant deterrent in the bio/pharma space either.

My current theory lies in the fact that most commercial products subject to litigation are protected by multiple (up to dozens or more) patents, and challenging a patent thicket via IPR is simply not an efficient way to proceed and it's possible that the low-hanging fruit has simply been plucked.time will tell.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.