On February 16, 2017, the Florida Supreme Court declined to adopt the Daubert standard for the admissibility of expert evidence into the Florida Evidence Code to the extent it is procedural in nature. See In re Amends. to the Fla. Evid. Code, No. SC16-181, 2017 WL 633770 (Fla. Feb. 16, 2017). To read the full opinion, please go here. The decision was supported by the plaintiffs' bar, who believed that the Frye "general acceptance" standard worked and argued that the more complicated Daubert standard would burden the state courts and negatively impact most clients by requiring courts to hold costly mini-trials to determine whether to admit an expert's testimony. The Court did not find that the Daubert standard is procedural or that it is unconstitutional. It left that fight for another day when it is presented with "a proper case or controversy."

Frye & Daubert

Effective July 1, 2013, the Florida Legislature adopted the Daubert standard for the admissibility of expert evidence, replacing the Frye standard. See Ch. 2013-107, Laws of Fla. §§ 1, 2 (amending sections 90.702 and 90.704 of the Florida Statutes). The Frye standard, which was adopted in Florida in 1952, admits expert testimony if the expert's testimony is based on a scientific principle or discovery that is "sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs." The Frye standard only applies to expert testimony that involves "new or novel scientific evidence," and does not apply to "pure opinion" or an expert's reasoning or conclusion. For example, if an expert uses scientific literature as a tool in helping form an opinion, then the court can and will scrutinize that opinion under Frye, but if the expert chooses to give an expert opinion without any basis in scientific literature at all, then his opinion is not subjected to the Frye test and is likely admissible. See Kenneth W. Waterway & Robert C. Weill, A Plea for Legislative Reform: The Adoption of Daubert to Ensure the Reliability of Exert Evidence in Florida Courts, 36 Nova L. Rev. 1, 11 (2011).

The Daubert standard, which has been applied by federal courts since 1993, applies to all expert testimony and admits expert testimony when it is both reliable and relevant. See § 90.702, Fla. Stat. (admitting expert testimony when it is "based upon sufficient facts or data," "the product of reliable principles and methods," and the expert "has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case").

The Majority Opinion

In its opinion, the Florida Supreme Court declined to adopt the Daubert amendment into the Florida Evidence Code to the extent it is procedural, citing "grave constitutional concerns" such as undermining the right to a jury trial and denying access to the courts. The procedural – substantive distinction is grounded on a separation-of-powers issue: the Florida Constitution grants to the Court the exclusive power to create rules of court procedure; this exclusive power does not extend to rules of procedure that are substantive, which are the province of the Florida legislature.

The Court did not find that the amendment was procedural or substantive and did not conclude that the amendment was unconstitutional. Because a rules case is not the proper forum for addressing the constitutionality of a statute or proposed rule, the Court deferred these issues until it is has a "proper case or controversy" before it.

The Dissenting Opinion

Justice Polston dissented in which Justice Canady concurred. Highlighting that 36 states have rejected Frye in favor of Daubert, Justice Polston asked and answered two questions: "Has the entire federal court system for the last 23 years as well as 36 states denied parties' right to a jury trial and access to courts? Do only Florida and a few other states have a constitutionally sound standard for the admissibility of expert testimony? Of course not." He also noted that he knew of no reported decisions that have held that the Daubert standard violates the constitutional guarantees of a jury trial and access to the courts. To the contrary, he cited cases holding that the Daubert standard does not violate the constitution. In the end, he found the majority's "grave constitutional concerns" over the Daubert standard to be unfounded and thought that the Court should adopt the Daubert standard.

What Now?

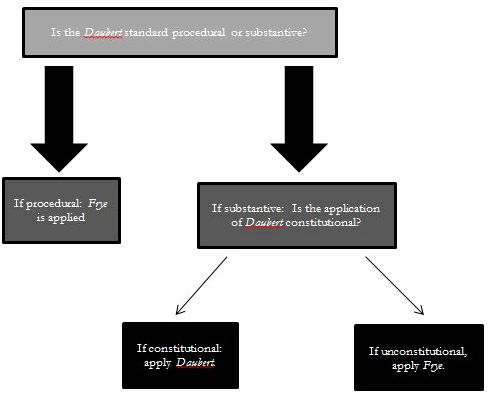

The Court's opinion leaves the door open as to whether the Daubert amendment is procedural or substantive and also whether it is unconstitutional. Until a case reaches the supreme court that tees up these issues, Florida attorneys will battle these issues in the trial courts. Because Florida courts have not established a bright-line test to resolve the procedural-substantive question, the law is a morass of conflicting definitions and principles. For example, at times the Florida Supreme Court even has held that a provision can be both "substantive" and "procedural." Because of the uncertainty in the law, every case may not be a battleground for these issues; attorneys likely will raise these issues when it makes sense from legal, strategic and cost perspectives. The following flow chart demonstrates the interaction of these issues:

Of course, inherent in some of these issues are additional issues. For example, the Daubert amendment became effective on July 1, 2013. Parties also may choose to litigate whether the amendment applies retroactively to causes of action that accrued before the effective date.

As for pending cases in the trial courts, parties who have had their experts' opinions stricken under the Daubert standard, may now try to seek reconsideration of that ruling arguing that the Frye standard should apply. As for cases pending on appeal where there is an issue involving the exclusion of an expert's opinion based on Daubert, the appellate courts may remand the issue back to the trial court in light of this material change in the law.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.