This is part 4 of a series of blog posts on the likely implications of a Biden Presidency on U.S. immigration policy.

Last week, President Biden signed three executive orders on immigration. The first aims to reunite migrant parents who were separated from their children at the border. The second seeks to grasp the root causes of migration at the southern border from Central American nations. Last, but certainly not least for our purposes, the third executive order requires government agencies "to conduct a top-to-bottom review of recent regulations, policies, and guidance that have set up barriers to or our legal immigration system."

As I have advocated in my recent posts, intentional and systematic erosion of the U.S.'s legal immigration system during the Trump administration requires a new tone at the top, a return to its original mission, and targeted efforts to make agencies more efficient in order to yield consistent adjudications and increase American competitiveness.

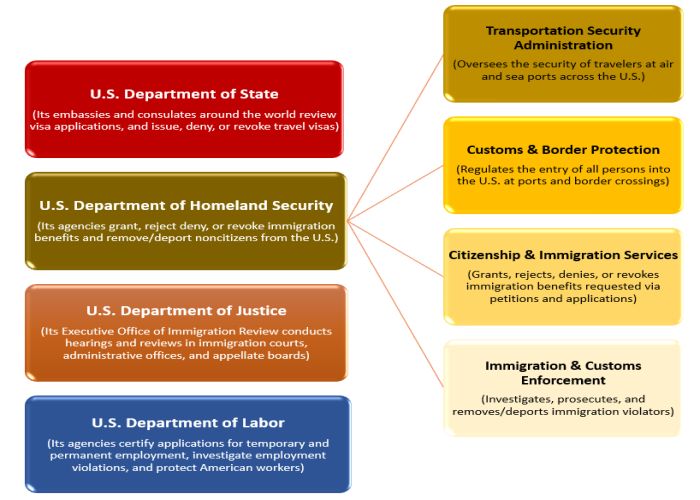

The Department of Homeland Security and its partner agencies, the Department of State and Department of Labor, jointly regulate various aspects of U.S. immigration laws. By ordering a thorough review of the regulations, policies, and guidance that have created a barrier to legal immigration, President Biden recognizes the devastating impact that such administrative tools have wreaked over the last four years. The effect of these barriers is well-documented, and more narratives are being identified and confirmed with each passing day.

In this post, I explore some of the more glaring inconsistencies that presently exist in the adjudication of U.S. immigration laws, and suggest actions the government can take in order to yield outcomes that support both immigration policy and the country's broader economic goals.

The Burden of Establishing Eligibility in Immigration Matters

When a company petitions for a non-citizen worker, or a U.S. citizen petitions for his or her foreign-born spouse, or a non-citizen applies for employment authorization in order to obtain post-graduate practical training, they are all seeking immigration benefits. Under U.S. immigration law, petitioners and applicants bear the burden of proof, meaning that they must provide evidence to show that they are eligible for the immigration benefits they seek. Unlike in criminal law, in which the government bears the burden to prove a defendant's culpability, in immigration matters, the burden of proof to establish eligibility falls squarely on petitioners and applicants.

Just how much initial evidence petitioners and applicants need to establish their eligibility depends on the standard of proof. In most administrative immigration matters, the standard of proof is preponderance of the evidence. As described in the USCIS's Policy Manual, in order to prove something by preponderance, petitioners and applicants must submit "relevant, probative, and credible" evidence to lead the adjudicator to the conclusion that the claims are "more likely than not" to be true.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Cardozo-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421 (1987), defined "more likely than not" as a greater than 50 percent probability of something occurring. In terms of probabilities, preponderance may be quantified as 51%, and is a lower standard of proof compared to clear and convincing evidence (71 percent) and beyond a reasonable doubt (91 percent). Kagehiro, D.K., Stanton, W.C. Legal vs. quantified definitions of standards of proof. Law Hum Behav 9, 159–178 (1985).

Consistent Criteria for Adjudicating Extensions

In my last post, I argued that reinstituting deference for previously-approved petitions generates efficiency. When adjudicators are not digging up old files, poring through the record, and sniffing around to find some evidence of ineligibility to deny an extension, they can instead focus their efforts on adjudicating current cases, decreasing the backlog, and increasing their agency's revenue stream.

Reinstating deference for prior approvals also fosters consistency. In common law systems, such as the United States, there is a sacred reliance on stare decisis, a Latin term that literally means "to stand by things decided." Under this principle, given a similar set of facts, judges will follow established legal rules to make consistent, predictable decisions as those made by other judges in the past. Historical adherence to stare decisis creates precedent from which – unless there is new evidence to the contrary – adjudicators must make the same decision as was made in the past.

President Biden's February 2, 2021 executive order, to conduct a comprehensive review of "recent regulations, policies, and guidance that have set up barriers to our legal immigration system," paves the way for the USCIS to rescind its October 23, 2017 Policy Memorandum that instructed officers to not defer to precedent when adjudicating extensions.

Reliance on precedent in immigration proceedings is not a foreign concept. In fact, the USCIS's Adjudicators Field Manual 10.17 already acknowledges the importance of deference in motions to reopen or reconsider cases that are filed with its District Offices, Service Centers, immigration courts, and its appellate bodies, the Administrative Appeals Office and the Board of Immigration Appeals:

Note 1

When considering any form of extension or similar benefit, and where the same parties are involved, USCIS will give deference to the previous decision. Deference is required even if there is a precedent or adopted decision. Furthermore, officers may only draw a different conclusion where there is a clear change or distinction in facts. Even in such instances, a supervisor must explicitly concur with the different conclusion.

Note 2

Unless there is a clear finding of fraud or substantial material misrepresentation, or the facts have clearly and distinctly changed, officers should not reopen a previously approved and valid application or petition. Even in these circumstances, a supervisor must explicitly concur with the different conclusion.

In rescinding deference in immigration extension requests, the Trump administration was placing yet another paper brick in its paper wall. It created new templates to encourage adjudicators to issue more Requests for Further Evidence (RFEs), which became duplicative and unduly burdensome when evidence supplied in the extension was ignored or rules were interpreted in a maliciously narrow manner.

Many of President Biden's early immigration actions will be to restore previously existing policies that were reversed by Trump and to regenerate respect for the rule of law. It is clear from President Biden's recent Executive Order that updating and formalizing USCIS's policies that govern how benefit requests cases are adjudicated across the board is at the top of that agenda and rightly so.

Training Partner Agency Personnel Involved in the Immigration Process

As depicted below, the administration of U.S. immigration laws involves multiple governmental departments and numerous agencies within those departments.

While most functions are statutorily defined, there is some overlap between agencies, which can lead to mindboggling inconsistences and serious consequences. Employment-based nonimmigrant visa holders – such as H-1B specialty occupation workers, or L-1A intracompany executives, or O-1 individuals with extraordinary abilities, or P-1A athletes – are the most common victims of such episodes.

To illustrate through a hypothetical, take Joe Public, an executive at a fictitious London tech firm, Acme Technologies (Acme UK).

Joe has been working as a CTO for Acme UK for two years. Acme UK now wants to immediately transfer him to the U.S. to lead the growth of its U.S. subsidiary, Acme Technologies Corporation (Acme US). Before Joe can enter the U.S. to work, however, Acme US must obtain an approval from the USCIS for Joe to work for Acme US in L-1A status. Acme US retains Harris Bricken to petition for Joe.

Harris Bricken meticulously prepares and submits Acme US's premium processing petition on behalf of Joe to the USCIS, demonstrating that Joe meets each L-1A eligibility criterion. USCIS approves the petition and issues the Approval Notice (I-797B) authorizing Joe to hold L-1A status for three years once he enters the U.S. Because Joe lives and works outside the U.S., however, once he receives the I-797B, he must use it to first apply for an L-1A visa foil in his passport at the U.S. Embassy in London.

Inconsistency #1 (consular officer second guesses the USCIS's approval for Joe to hold L-1A classification): even though the USCIS has approved Acme US's exhaustively-evidenced petition for Joe, the visa officer at the Embassy feels that Joe's technical degree does not adequately prepare him to lead Acme US's business expansion. The visa officer puts Joe's case in administrative processing until he can provide letters from experts proving otherwise.

After Joe and Harris Bricken work feverishly to supply the expert letters to the Embassy, the visa officer approves the visa application and affixes the L-1A visa in Joe's passport. Joe and Acme US have now had to prove Joe's qualifications to a second government agency (the U.S. Department of State) even though one government agency (the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) had approved the petition previously.

Inconsistency #2 (Joe's L-1A validity is limited to the expiration of his passport, not the expiration of the I-797B): Joe travels to the U.S. with the L-1A visa foil. At the port of entry, however, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer limits his stay in the U.S. to the date his passport expires (in one year) instead of the expiration date indicated on both the I-797B and L-1A visa foil (three years). The result of this technicality is that Joe can only remain in the U.S. in L-1A status for one year even though he thinks he has L-1A status for three years. To rectify this inconsistency, even if Joe renews his passport at the British Consulate General in San Francisco, he will still need to leave the U.S. before his stay expires next year and then reenter the U.S. In order to be lawfully readmitted for the full L-1A validity period, Joe would need to show the CBP officer not just his new passport, but also the old passport which contains the L-1A visa foil, along with his original I-797B. He must also be able to articulate why he is presenting all of these documents and how he has maintained his L-1A status, and also verify that the CBP officer has admitted him for the full validity period.

Inconsistency #3 (USCIS does not give deference to its prior approval when adjudicating his L-1A extension): Fast forward to a few months before Joe's L-1A status is scheduled to expire. Acme US wants to extend his L-1A status for two more years. Harris Bricken prepares the extension and provides ample evidence that Joe remains eligible for L-1A status and has maintained that status in the U.S. In reviewing the extension, the USCIS officer decides to look at Joe's eligibility all over again and asks for all pay statements and performance reviews from when Joe was employed by Acme UK dating back five years. Joe and Acme UK have to scramble to locate that evidence to convince the USCIS now why it approved the initial petition back then.

These series of inconsistencies break Joe's patience, and even though Acme US wants to sponsor him for permanent residence so he can solidify the company's U.S. footprint, he decides to return to London, stunting Acme US's growth in the process.

The difficulties illustrated above are all too common. They are also entirely avoidable simply by designating USCIS's approval as definitive, by granting the full validity period to visa holders who enter with valid visas and I-797s, by reinstating deference to precedent as USCIS policy, and by investing in intra- and interagency training to foster consistency and coherence in the application of immigration laws.

In my next and final post in this series, I will suggest ways that the Biden-Harris administration can tap into talent that holds tremendous promise to help restore American innovation, competitiveness, and leadership.

This is part 4 of a series of blog posts on the likely implications of a Biden Presidency on U.S. immigration policy. Read the first post here. Read the second post here. Read the third post here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.