In recent years, the rise of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) has taken the world by storm, with individuals and companies alike attempting to capitalize on the new technology. One such company is Burberry, a British luxury fashion house, who attempted to register an EU trademark for a range of NFT-related products and services. However, the company's application was met with a partial refusal by the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), which covers almost all of the goods and services listed in the application, with the exception of downloadable interactive characters, avatars, skins, video games, downloadable video game software, and certain services related to computer games.

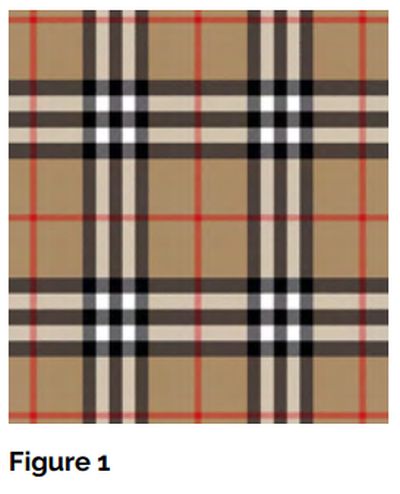

BURBERRY filed its famous figurative application [Figure 1] on 02/02/2022 for the following classes:

"9 - Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) or other digital tokens based on blockchain technology; downloadable digital graphics; downloadable digital collectibles; downloadable clothing and accessories; downloadable interactive characters, avatars and skins; downloadable virtual goods; virtual bags, textile goods, clothing, headgear, footwear, eyewear all displayed or used online and/or in virtual environments; video games and downloadable video game software; downloadable digital materials, namely, audio-visual content, videos, films, multimedia files, and animation, all delivered via global computer networks and wireless networks."

"35 - Retail and wholesale services for clothing, footwear, headgear, bags, purses, wallets, umbrellas, watches, jewellery, eyewear and sunglasses, cases and covers holders for portable electronic devices, printed matter, homeware, toys, perfume, toiletries and cosmetics, textile goods, pet accessories; online retail services related to fashion, clothing and related accessories; Retail store services and/or online retail store services in relation to virtual merchandise namely clothing, footwear, headgear, bags, purses, wallets, umbrellas, watches, jewellery, eyewear and sunglasses, cases and covers holders for portable electronic devices, printed matter, homeware, toys, perfume, toiletries and cosmetics, textile goods, pet accessories; presentation of goods on communication media, for retail purposes."

"41 - Providing online non-downloadable digital collectibles namely art, photographs, clothing and accessories, images, animation, and videos; providing on-line information about fashion shows, digital games and sustainability; entertainment services, namely providing on-line, nondownloadable virtual content featuring clothing, footwear, headwear, bags, purses, wallets, umbrellas, jewellery, eyewear and sunglasses, cases and covers holders for portable electronic devices, printed matter, homeware, toys, perfume, toiletries and cosmetics, textile goods, pet accessories, for use online and/or in virtual environments; providing online video games; provision of online information in the field of computer games entertainment; entertainment services, namely, providing online electronic games, providing a website with non-downloadable computer games and video games, computer interface themes, enhancements, audio-visual content in the nature of music, films, videos, and other multimedia materials."

The refusal is based on the grounds that the trademark application lacks distinctiveness, as the check pattern used is not markedly different from other patterns commonly used in the trade for the goods and services for which an objection has been raised. The examiner further stated that "the consumer's perceptions for real-world goods can be applied to equivalent virtual goods as a key aspect of virtual goods is to emulate core concepts of real-world goods."

This decision has raised questions about how trademarks for virtual goods should be analyzed and the extent to which they should be treated in the same way as trademarks for physical goods.

EUIPO's notice on NFT's classification stated that virtual goods should be categorized as Class 9 goods, which include digital content or images. However, the term "virtual goods" on its own lacks clarity and precision, so it must be further specified by stating the content to which the virtual goods relate, such as "downloadable virtual goods, namely, virtual clothing." The 12th edition of the Nice Classification already incorporates the term "downloadable digital files authenticated by non-fungible tokens" in Class 9. EUIPO then requires that the type of digital item authenticated by the NFT must be specified within the classification.

The partial refusal of Burberry's trademark application shows that EUIPO is taking a cautious approach to trademarks for virtual goods, as they are still relatively new and there is little legal precedent for them. The decision also highlights the importance of ensuring that trademarks for virtual goods are distinctive and do not simply replicate patterns or designs that are commonly used in the trade.

However, it is possible to criticize the decision, arguing that the distinctiveness analysis for trademarks for virtual goods should not necessarily be the same as for physical goods. Virtual goods have unique features that may not apply to physical goods, and their distinctiveness may depend on factors such as their rarity or uniqueness, rather than their design or branding. Furthermore, the value of NFTs lies in their blockchain authentication, which makes them unique and valuable, and the trademark for the NFT could reflect that uniqueness.

The decision also raises questions about the broader legal implications of NFTs and virtual goods. As more companies and individuals begin to use NFTs to sell and authenticate digital art, collectibles, and other goods, there may be a need for new legal frameworks to regulate and protect these transactions. NFTs raise questions about ownership, copyright, and intellectual property, as well as the potential for fraud and theft. It is likely that regulators and legal experts will need to develop new rules and regulations to address these issues in the coming years.

In the meantime, companies that are interested in trademarking their virtual goods will need to carefully consider the distinctiveness of their trademark and designs, and ensure that their trademarks are not simply replicating patterns that are commonly used in the trade.

To conclude, the recent partial refusal of Burberry's NFT trademark application highlights the challenges and considerations that trademark applicants and examiners face in the emerging world of NFTs and virtual goods. The decision by EUIPO to refuse the trademark application indicates that virtual goods must be analyzed in the same way as real-world products when assessing their distinctiveness and potential for trademark protection. This means that NFT trademarks must be sufficiently distinct from other common patterns in the trade, just like any other physical product.

As more and more companies enter the world of NFTs and virtual commerce, it will become increasingly important for them to carefully consider the distinctiveness of their trademark and the potential for trademark protection in this new digital landscape. Additionally, trademark offices around the world will need to develop clear guidelines and standards for evaluating NFT trademarks to ensure that they are assessed fairly and consistently.

The refusal serves as a reminder that while NFTs and virtual goods offer exciting new opportunities for businesses and consumers, they also present unique legal and intellectual property challenges that require careful consideration and expert guidance.

Originally published by The Trademark Lawyer Magazine.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.