The Rugby World Cup is the third most-viewed sporting event in the world. Twenty teams, one winner. The 2023 edition kicks off in France on 9 September 2023, and shapes as one of the most open yet, with up to eight nations peaking at the right time and no real inter-hemisphere competition over the past ten months to act as a comparator.

On its face, rugby is a "pick-up" game that requires little by way of fancy or elaborate kit with which to compete. A ball, a field, two teams, preferably a referee – and we have ourselves a game. Compare that with motorsport, sailing, etc. – sports where innovation is king, and it's easy to presume that the link between rugby and IP is a tenuous one. However, sweep the sheds and you'll see there's actually an extensive history of IP as it pertains to rugby. In fairness, much of this is derived from its collision sport similarities with American football, but there is also a substantial body of rugby-specific IP out there.

In this article, we cast our eyes over some of the patents that won't be making an appearance (at least as a protected product or process) in France – and hopefully give the same impression we gleaned in preparing this article. Namely, that despite its nature, rugby nonetheless invites some significant out-of-the-box thinking.

1. A PlayStation for props

Following a singularly unremarkable three decades of playing in the front row, it is perhaps unsurprising that "scrumology" is a pet subject. You see, hear and smell things that all the therapy in the world isn't going to undo. But beyond the societal aspect of scrummaging, there's also a highly technical and nuanced craft to be deployed – and this is where scrum machines (or sleds) come in. A training device built to receive a scrummage and weighted either with teammates or some other ballast (I've even seen kegs of beer used) in order to provide some resistance to what is often more than 800 kg of flesh pushing in unison. Scrum practice is all part of the delight of playing this great game.

WO 2007/054564 is derived from France, where they know a thing or two about scrummaging. It is entitled "Device for training and/or measuring forces of rugby players and corresponding method for training and/or measuring efforts of rugby players", and we think that sums it up quite nicely. In technical terms, it's a scrum machine with pressure sensors producing measurable outputs for analytical purposes. In layman's terms, it's a way of measuring who's putting in and who's taking it easy during scrum training. And in practical terms, it's a means by which coaches can assess which of their looseheads is a stronger scrummager, what pressure imbalance is needed to promote the tighthead side on opposition ball, or how the flankers can influence forward thrust on their respective sides by squeezing up and in. In short, it's almost like a PlayStation for props. The banter this machine might've enabled would've been epic.

Obvious limitations include the fact that all the simulated scrum practice in the world tends to go out the window as soon as you're faced with "live" opponents (see/hear/smell, as above), and that scrum machines occupy a somewhat niche commercial space with, strangely, not everyone wanting or needing one.

WO'564 ended up entering the European regional phase, but was not prosecuted actively and was deemed withdrawn in 2014. The patent literature was the winner on the day.

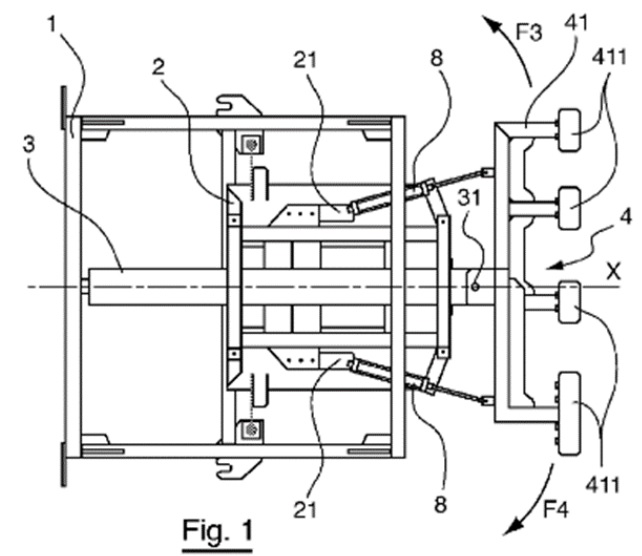

Figure 1 shows a fairly regular looking scrum machine in plan view, with the "magic" happening at features 8 and 21.

2. One tee to rule them all

Moving quickly from scrums to another great aptitude of any self-respecting front-rower, goalkicking. There are a number of patented kicking tees (think a golf tee for a rugby ball) out there, however, most of them seem designed for American football. The crucial distinction reflects the current trend for rugby kickers to lean the ball forward in order to expose more of the "sweet spot" to a kicker's boot. By contrast, do this with an American football and the best-case scenario is that you end up with a sore foot. Therefore, rugby tees and American football tees aren't quite as interchangeable as one might suspect at first blush.

Another observation is that some kickers lean the ball only slightly forward (Dan Carter and Jonny Wilkinson weren't too bad) whereas others like to lean it quite a long way forward (Beauden Barrett and Jonathan Thurston come to mind). Not all tees will enable the ball to balance across its possible arc of placement, and this is presumably what led to the invention described in WO 2006/024053.

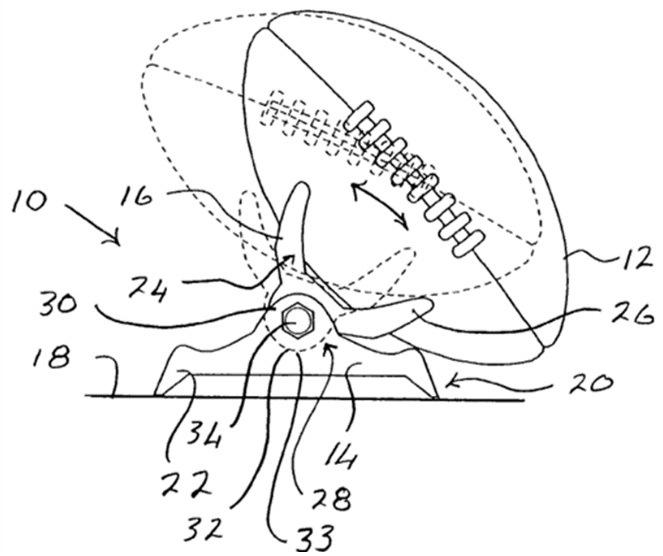

In Figure 1, below, the ball sits in a cradle (16) which is hingedly mounted on a base (14) via a shaft (34). The cradle is rotatable through an arc, which allows an individual kicker to obtain his/her preferred slant on the ball – solid lines for Carter, dotted lines for Barrett. Kickers may also opt for different slants depending on which side of the field they are on, wind conditions, etc.

All up, we think this is quite a neat idea. Whereas the ISR and Written Opinion weren't especially damning, this application never made it beyond the PCT International Phase. Upon a quick search, it doesn't appear to have been commercialised either (although we must say there's a surprising amount of competition within the $20 plastic kicking tee market).

3. Practice makes perfect

The number of rucks occurring in Rugby World Cup games has increased from an average of 25 per game in 1987 to just over 80 in 2015 and 2019. That's going from one every three minutes to one every minute.

It's one of the murkiest areas in the game of rugby, perhaps second only to scrums, and split-second timing is essential in the transition from tackle to ruck if a player wants to avoid the wrath of the referee. The relevant law in The Laws of the Game is "15 Ruck", and there are nineteen subsections relating to the forming and ending of a ruck, plus everything you theoretically can or cannot do in between. Needless to say there is a lot of scope for error on the part of players and consequent whistling from the ref.

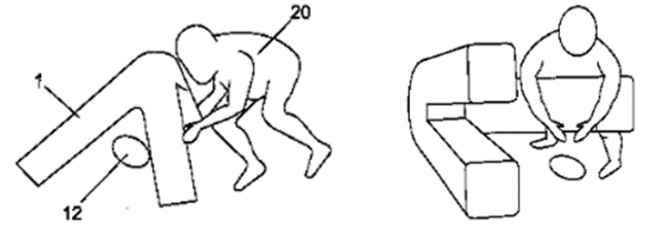

WO 2009/047527 describes a simple tripod that simulates a player's torso and two of their arms and/or legs, and the positioning of the tripod on the ground can replicate various ruck formations.

These formations favourably simulate those appearing in Law 15, shown below.

Source: https://www.world.rugby/the-game/laws/law/15

We imagine this would be an effective training apparatus for beginners despite the static nature of the device. Live action rucks, in practice or in a match, are much more fluid, testing the limits of the law.

This PCT had only one national phase entry, in Great Britain, which was withdrawn before grant. The ISR lists two "X" documents which relate to tackling dummies, so are similar in that they have a torso and limbs (of sorts), but neither describes the tripod, while a third "X" document relating to a wrestling training device does appear to show one of the alternative embodiments of the PCT publication.

4. The true gauge of a fan's devotion

Enthusiastic fans of all sports support their favourite player, team or country by wearing a numbered or named jersey, or a scarf or beanie. Sometimes, they paint their face or body in the team's colours.

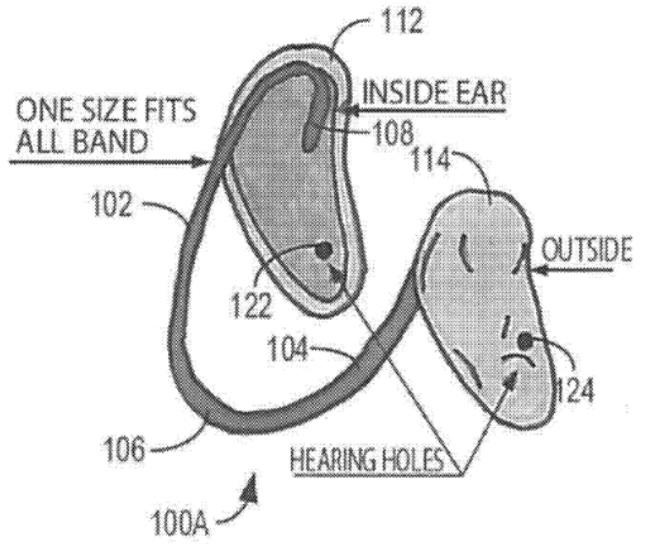

US 2013/0326793 takes things a step further. It's for the fan who likes to go above and beyond. What could show more support than to wear a set of cauliflower ears based on those of your favourite player? We can't think of anything better, and here they are.

Just like every other piece of fan clothing, the ears can display team colours, player names or numbers, or advertising. Other features include noise suppression, insulation for warmth and headphones, and most importantly, attachable wigs mimicking the signature haircut of a player such as Ardie Savea, Rob Valentini or even Joe Marler(!)

The patent family contains only the US application and a Canadian equivalent. Both lapsed under the weight of examination. There were many citations relating to ear-shaped headwear, and a few related to moulds of an ear. Although none that appeared to link the two concepts, in the end neither were granted.

5. Lift your game

In rugby, a lineout is how possession is contested after the ball goes out of play. In the old days, lineouts were a bit of a free-for-all with a flurry of arms and legs everywhere and the ball ungainly swatted back towards the halfback, who would usually receive two or three opposition forwards at the same time. However, with the advent (legalisation) of lifting shortly after rugby went professional, this has all changed. Nowadays, it's almost symphonic as 120 kg locks are thrown effortlessly into the air by their lifters. Originally, the lifters grabbed the jumpers by their shorts and projected them vertically. Then, as teams started striving for more height in the jump, it became necessary to grab onto a jumper's legs. Only one problem there – it's not especially easy to grab a heavily-perspiring 120 kg lock just above the knees and obtain sufficient grip to assist much at all.

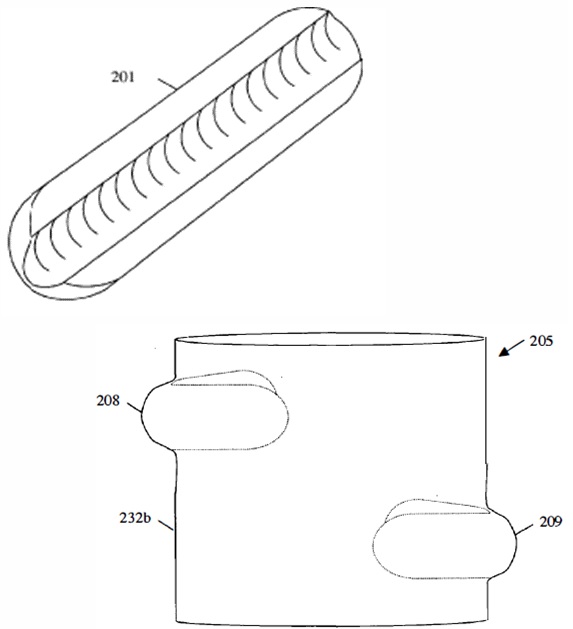

US 2009/0271907 describes a leg handle used to aid in lifting a jumping player, especially for rugby lineouts. The leg handle (poetically referred to as "sausage" in the specification) can be attached to a thin stretch fabric sleeve placed on the leg of a player. It can also be taped on with strapping tape. The sausage supposedly allows secure grasp and improved lifting performance.

Unfortunately, the patent application didn't survive USPTO examination against a number of cited documents. With that said, such handles (or variations thereof) are now used routinely across all levels of rugby, enabling ever-stronger lifters to project ever-bigger jumpers ever-higher.

6. Back to the drawing (gaming) board

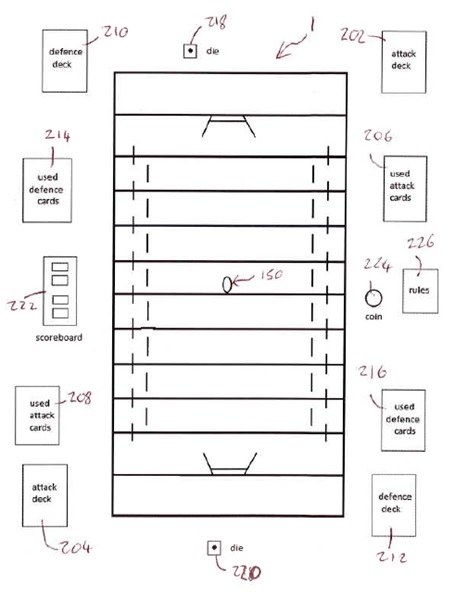

It seems Australia's love of rugby is not limited to the field – it also motivates footy fans to invent their own board games.

AU 2021200114 describes a rugby league board game in which a ball is "kicked" by flicking a player's finger to simulate the projection of the ball. The specification also includes a sophisticated set of rules on pages 24 to 33 (surely no more complicated than the tackled ball rule in actual rugby).

Again, the patent application did not proceed to grant, and according to the sole examination report, such a board game dates back as early as 1988. In fact, a couple of us can think of one growing up. The cricket equivalents were a hoot.

Game time!

With less than a week now until RWC23 kicks off, things are starting to get serious. This article hopefully keeps things in perspective as, at the end of the day, there will be 19 disappointed teams and nations. With unashamed objectivity, 67% of the authorship is tipping (hoping) that the team in black won't be among them.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.