The "non-use of trademarks" is a legal concept that pertains to not using a registered trademark for an extended period after its registration.

This mechanism is justified to prevent trademarks from being registered and maintained solely for speculative or strategic purposes without genuine commercial intent. It aims to ensure fair competition and the availability of trademarks for genuine and commercial use while discouraging the creation of a "trademark graveyard," as referenced by Professor Remo Franceschelli.

In such cases, numerous trademarks are registered but left inactive, often to block competitors, and this practice can be detrimental to fair competition and innovation.

To address this, many trademark systems require continuous use of a trademark after registration, and if the trademark owner fails to use it within a specified period, typically a few years, the trademark may be challenged and eventually cancelled.

This helps maintain the integrity of the trademark system by ensuring trademarks are genuinely used for commercial purposes, rather than being held as inactive assets that impede competition.

Despite the principles of non-use cancellation being globally harmonised, there are specific steps to be taken, differing from one jurisdiction to another that shall be mentioned below with particular emphasis on the African continent.

Notwithstanding, when pursuing the cancellation, there are typically various types of documentation to support it. Here is a summary of the general documentation that may be necessary:

- Evidence of Non-Use: evidence that the trademark owner has not actively used the trademark in the relevant jurisdiction such as documentation that the trademark has not been used in advertising, proof that it is not in use on products or services and sales records.

- Trademark registration i

- Proof of legitimacy: demonstrating the eligibility for trademark cancellation based on non-use. This might involve proving that the applicant is an interest party, for instance, a competitor.

- Correspondence with the trademark owner (if any): if applicable, retaining copies of such communication might be helpful.

- Witness statements from individuals attesting to the non-use.

- Advertising: by providing any advertising related to the trademark that demonstrate a lack of use.

- Financial Records: showing profit and loss statement.

In Africa, some countries have well-established trademark systems, while others are still developing their intellectual property regulations. Typically, in African countries, only certain parties with a legitimate interest in the trademark may file for cancellation based on non-use. These parties often include competitors or individuals who can demonstrate a direct interest in the trademark.

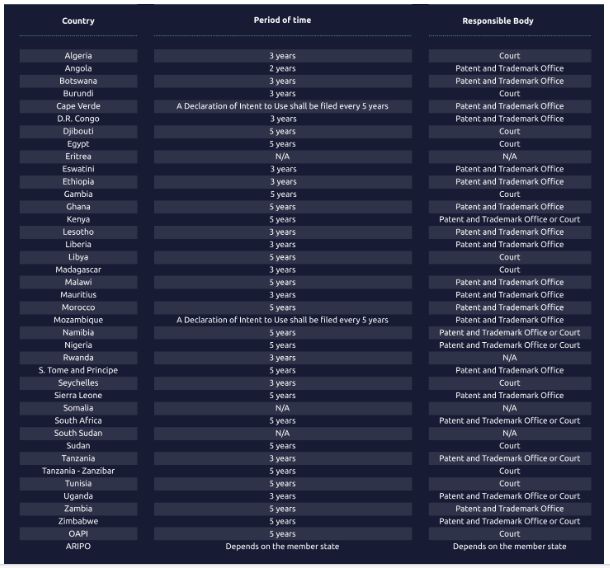

Here is a summary of the deadlines and competent authorities responsible for deciding the cancellation of a trademark based on non-use in all African countries:

In South Africa, non-use cancellation requires a continuous period of five years of non-use, meaning sporadic use or low sales volumes would suffice in defence of non-use proceedings. To defend a cancellation, the owner must show it was indeed used in the relevant 5-year period.

The Supreme Court has also established a good faith requirement: Westminster Tobacco Co v Philip Morris Products SA (925/2015). The High Court ruled that genuine use entails using a trademark on products exclusively to advance the trade of those products. Use for other reasons, such as disrupting a competitor's business or safeguarding the trademark owner's trade in different products, does not qualify as genuine use. Furthermore, it was established that the use does not have to be extensive but genuine.

Differently, in Mozambique, it is not possible to proceed with a cancellation on the grounds of non-use. Although the cancellation may be provided if the owner did not file a DIU (Declaration of Use) by the respective due date—a cancellation may be requested by an interested third party on the grounds of an overdue DIU and the trademark owner, in this case, does not have an opportunity to oppose the cancellation request.

Checking the requirements of the cancellation actions is crucial to determining the requirements of each national law. Hence, conducting meticulous research and availing oneself of legal counsel well-versed in the trademark laws pertinent to the targeted jurisdiction is indispensable.

Furthermore, the Banjul Protocol (ARIPO) explicitly states that the rights granted are subject to the national laws of each designated country. Therefore, ARIPO's role is limited to being a receiving office, and all substantial aspects related to trademarks, such as the need for use, are the responsibility of each individual country. Consequently, the process of cancelling a trademark due to non-use will adhere to the specific regulations of each state.

In Cape Verde, there's a hybrid system that allows, simultaneously, filing cancellation for non-use or non-submission of a DIU.

The time frames in which the cancellation shall be requested are, also, different in each jurisdiction. For example, in Eswatini, Lesotho, Liberia, Tanzania, Botswana, Uganda and Ethiopia it's only three years. On the other hand, in South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe it's required five years.

In summary, the importance of using trademarks to prevent cancellation actions cannot be understated. Trademarks are essential assets that protect your brand's identity and market presence. Neglecting them can lead to the loss of rights and significant legal expenses.

Checking the requirements of the cancellation actions is crucial to determining the requirements of each national law. Hence, conducting meticulous research and availing oneself of legal counsel well-versed in the trademark laws pertinent to the targeted jurisdiction is indispensable.

This approach ensures that the cancellation action is executed in strict adherence to local regulations, thereby enhancing the prospects of achieving the desired outcome.

This is a co-published article, which was originally published in the World Intellectual Property Review (WIPR)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.