A. AUDIENCE, PURPOSE AND SCOPE

1. Who should read this white paper? The primary audience for this white paper is the in-house lawyer who is not a Tech specialist and who works at an organisation that is not a Tech provider company, but which acquires IT. The secondary audience is the in-house lawyer at a Tech acquirer company looking after IT and related aspects of the business. The white paper may also be useful to the in-house lawyer at a Tech provider company on the sales side who wishes to understand what her or his counterpart at their Tech acquirer customer will be thinking about or looking out for.

2. Purpose and scope. This white paper provides an overview of the five main kinds of Tech and communications procurement and deployment: equipment, software, data, services and telecommunications (Section B below). IT also briefly examines the current trends in IT as they may affect the organisation (Section C).

Previous editions of this white paper have considered the Tech lawyer's role in the organisation and Tech types and Tech trends together in a single white paper. In this edition, we have separated the Tech lawyer's role in the organisation into a stand-alone white paper which is also available on our website at www.kempitlaw.com.

This white paper is intended as an introduction. It is not legal advice and is not intended to be comprehensive. In this white paper, we use 'IT' and 'Tech' interchangeably.

B. TYPES OF TECH/COMMUNICATIONS PROCUREMENT AND DEPLOYMENT

3. Introduction. To those unfamiliar with it, the range of Tech contracts and related legal matters may seem daunting. In demystifying, it is helpful to break the area down into its key component parts. These are, essentially, five:

- equipment (paragraph B.4);

- software (B.5);

- data (B.6);

- services (which we've divided into three:

- development, outsourcing and support (B.7));

- the cloud (B.8);

- digital commerce (B.9)); and

- telecoms (B.10).

4. Equipment. Equipment can be divided into two main types:

- User equipment covers PCs, laptops, tablets, smart phones, and other devices that the organisation's people use in their day-to-day work: in network terminology, "client-side".

- 'Server-side' equipment historically consists of servers, storage devices, cabled and Wi-Fi networking, back-up power sources, routers, switches and the like. Other equipment also includes the organisation's telephones and communications equipment together with document production and other office equipment.

5. Software. Computer software (programs) is a set of instructions that tells the computer what to do. It can be categorised by type of code, development model, whether product or bespoke, type of function, licensing and distribution and delivery model.

- Code type: a computer program is generally written as source code, a form in which it is human readable. For source code to be run on and understood by a computer it needs to be compiled (translated) into machine code, a version of the program in binary format (consisting of 0s and 1s) that is not human readable. Machine code is also known as object, binary or machine-readable code and the program in this form is known as an executable.

- Development model:

- software was traditionally developed in a highly structured ("cathedral") way and on a proprietary model by developers whose ownership of the copyright in the code is the asset they license and monetise. Proprietary developers typically just license the object code and are loath to license source code (except through a mechanism called escrow where the source code is deposited with a trusted third-party escrow agent authorised to release it to licensees on triggering events like the developer's insolvency).

- This model has been successfully challenged by open-source software ("OSS"), a community development model that is much less structured ("bazaar") and where the underlying source code is made freely available under standard licences. Marc Andreessen, the co-founder of web browser Netscape, famously said in 2011 that software was eating the world, and to that aphorism may be added that OSS is eating software.

- OSS has long since become ubiquitous and most organisations now operate in a mixed environment using both proprietary software and OSS. It's important to appreciate that the difference between proprietary software and OSS is not in the code (which is the same in both cases) but in the licensing 'wrapper' applied to the software.

- The key OSS risk to be aware of is that some OSS licences (like the General Public Licence ("GPL") and Lesser General Public Licence ("LGPL") of the Free Software Foundation ("FSF")) operate an 'inheritance' (or 'copyleft') requirement. This means that proprietary software interacting with this kind of OSS may in certain cases itself become compulsorily open sourced as a condition of using the OSS in the first place.

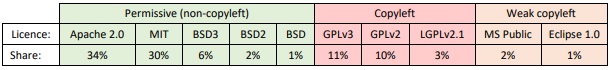

Recent years have seen a decline in the popularity of copyleft OSS licences and a corresponding rise in the uptake of permissive licences like the Apache 2.0 and MIT licences that do not impose inheritance requirements. A recent report2 shows the top 10 OSS licences by share as follows:

- Product or bespoke: Software can be either product (off-the-shelf), bespoke (customised or developed) or a mix of the two. Increasingly, for enterprise (large organisation) and SME (small to medium enterprise) customers, off-the-shelf software needs to be tailored (tuned or parameterised) 'out of the box' to make it suitable for use.

- Functionality type: software is either operating system,

application or middleware.

- The operating system ("OS") is the computer's traffic cop. It controls how resources – input, processing, memory, storage and output – are used in the most efficient way;

- Application software is the software functionality you use on your device (like an Office document on your laptop or an app on your smartphone) or through the Cloud or a server-based network across the enterprise (like Oracle, SAP or other enterprise resource planning ("ERP") software). The application sits on top of the OS. It requests the OS to use the computer's resources to perform tasks that it does not have permission to execute directly. These requests are made through system calls or application programming interfaces ("APIs"). A system call is a specific service request made directly by the application to the OS. An API is a set of requirements or specification which the application must comply with in order to obtain a particular service from the OS.

- In ERP/enterprise applications and the Cloud, middleware sits between the application and the OS to provide database and further resources to support the application.

- Licensing and distribution: like a book,

software is protected as a literary work by copyright and so is

licensed. A licence is permission to do something

that the law could otherwise stop you doing. Software licences are

typically on a subscription (periodical, e.g. monthly or annually)

or a perpetual (one-off) basis. Product software, as software

licences (whether subscription or perpetual), is

distributed directly by the developer itself or

indirectly through the developer's 'channel'.

- In direct software distribution, the software developer

directly licenses the end user to use the software on the terms of

an End User License Agreement ("EULA")

or (increasingly in the cloud world) Terms of Service

("TOS").

- In business to consumer ("B2C") direct software licensing, the end user typically accepts the EULA or TOS by clicking on a radio button on the developer's website (whether or not they pay a fee) and downloading or otherwise accessing the software to use.

- In business to business ("B2B") direct licensing, the end user and developer may negotiate and sign the EULA or TOS (for higher value deals) although here the trend is increasingly for EULAs and TOS to be click wrap accepted as in B2C;

- In indirect software distribution, an intermediary is

interposed between the developer and the end user. Intermediation

applies to both subscription and perpetual software licensing and

increasingly to Cloud services and may take many forms.

- In agency, the agent intermediary introduces the end user to the developer and takes a commission on the sale, with the commission revenue only (and not the sale price) going into the agent's P&L as income.

- In distribution the distributor or reseller intermediary buys

from the developer and sells on to the end user, with the purchase

and sales price going into the distributor's or reseller's

P&L as an expense (on the purchase) and income (on the

(re)sale). Here, the EULA may still run directly between the

developer and the user, where the distributor buys and sells not

the EULA itself but the right to the EULA. (From the end user's

point of view it is paying the price to the distributor or reseller

directly but getting the EULA from the developer). Alternatively,

the distributor may buy in and sell on the EULA.

Distribution may be one tier (developer → reseller → end user) or two tiers (developer → distributor → reseller → end user). Distributors take a number of forms, including:- OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) who typically pre-load software on a device and sell the two together;

- VARs (value added resellers) who sell the software and also provide other services, typically professional services in the case of enterprise software;

- wholesalers who focus on volume and the efficiency of their systems; and

- Appstore providers who connect mobile users to the developer (see C.17 below).

- In direct software distribution, the software developer

directly licenses the end user to use the software on the terms of

an End User License Agreement ("EULA")

or (increasingly in the cloud world) Terms of Service

("TOS").

The development of the Cloud is tending to disintermediate software distribution so that increasingly developers license end users directly, although here also we are seeing a growing distribution channel for Cloud services.

- Delivery model. Software is delivered (or deployed) "as a licence" or "as a service" (for SaaS, PaaS and IaaS, see B.8 below). If as a licence, the software generally (but not always) resides onpremise – in the organisation's server room or data centre. If as a service, the software generally sits in-cloud at the data centre of the organisation's cloud service provider.

Click here to continue reading . . .

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.