Executive summary

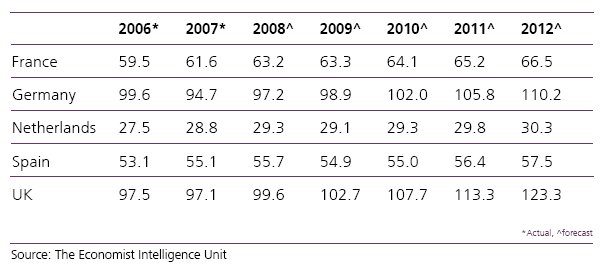

Despite a downturn in the global economy, and the potential short-term effects this may have on the industry, the long-term prospects for the aviation sector are healthy. While the Economist Intelligence Unit expects the number of global air passengers to grow at just 2 per cent in 2009 – with the number in Europe stagnating completely – between 2010 and 2012 strong growth of 4.2 per cent globally and 2.9 per cent in Europe is expected.

One might assume, therefore, that prospects for European airports would be equally rosy. However, growth in air traffic will be faster than the increase in capacity in Europe's already-overstretched major airports.

If European airports cannot keep up with demand, then airlines will look outside the region. Particularly vulnerable will be connecting services – which account for between a third and a half of all passengers at Europe's major hubs. European airports – which, thanks to the liberalisation policies of the EU, have begun to compete among themselves – are already feeling the pressure from global hubs, notably in the Middle East.

While there would be no shortage of potential investors to fund expansion in Europe, regulation and environmental concerns will prove to be obstacles in meeting capacity demands. Planning regulation and strict environmental restrictions will delay a much-needed third runway at Heathrow until at least 2020. In addition, the economic regulation of airports will restrict revenue from aeronautical services.

There are still opportunities for European airports, however. In particular – for those airports that pursue a policy of diversification – maximising nonaeronautical revenue streams such as retail, energy and property. As with the airline industry, another strategy may be consolidation, such as the recent tie-up between Paris Charles de Gaulle and Amsterdam Schiphol. Unlike in the airline industry, though, the scope for consolidation will be more limited.

Main findings

- As aeronautical revenue comes under pressure, European airports will need to diversify into non-aeronautical activities.

- Capacity is likely to fall well behind demand over the coming years, as regulation stymies expansion.

- This will expose European airports to ever-greater global competition, particularly from the up-and-coming Middle Eastern hubs.

- Europe airports will, however, remain an attractive proposition for longterm investment.

Introduction: no capacity for change

Little, it seems, is ever intuitive when it comes to European airports. That air passenger numbers are forecast to grow handsomely over the next ten years, one might assume, would be nothing but a fillip for a beleaguered industry. That they will do so far beyond existing airport capacity – and, indeed, any planned expansion in the region – turns seemingly good news into a potential competitive headache for operators.

A gloomy prognosis is informed by the lack of a pan-European strategy to tackle the bottleneck, and made worse by the fierce competition coming from swanky new airports in the Middle East and burgeoning Asian economies, which are more than happy to target disillusioned carriers. Add into this mix the current economic climate, which is sucking the lifeblood out of European airports as airlines suffer a temporary stagnation in traffic, and suddenly even the high price of oil starts to look like one of the industry's more minor nuisances.

Figure 1 – air passenger forecast

In normal market conditions, airports are viewed as cash cows. But if airlines are hurting, it means airports are too. British Airways' announcement in November of a 91 per cent drop in half-year profits – blamed chiefly on the surge in the oil price and a fall in business class passengers – typifies the situation. Fewer flights and fewer passengers mean that airports take a hit on both their major sources of income. Airline passengers and the airlines themselves provide a rich revenue stream from both aeronautical and, increasingly, non-aeronautical sources. Infrastructure, facilities and ground handling services make up their aeronautical services revenues, while car parks and retail concessions make up their non-aeronautical services.

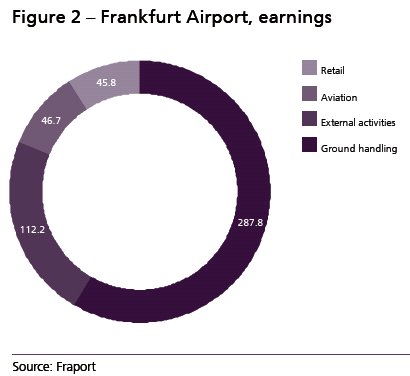

For example, Frankfurt airport, one of Europe's main airport hubs, cites four revenue streams in its latest figures covering the first nine months of 2008: ground handling (€483.7m), aviation (€533.5m), retail and property (€320.8m) and external activities (€261.8m).

Look more closely and the largest percentage of its earnings before tax and depreciation (EBITDA) derive from a non-aeronautical activity, that of retail, at €287.8m. Aviation comes in second at less than half that amount (€112.2m), followed by external activities (€46.7m) and ground handling (€45.8m).

Figure 2 – Frankfurt Airport, earnings

Diverse strategies

But perhaps the forecast isn't unremittingly depressing. Despite their problems, what will help the major European hubs is their lucrative transfer traffic that accesses all parts of the world, traffic that is usually more resilient than point-to-point travel when the pressure is on. Transfers account for 56 per cent of traffic at Frankfurt, 41 per cent at Amsterdam Schiphol, 34 per cent at Paris Charles de Gaulle (CDG) and 32 per cent at London Heathrow. Smaller point-to-point airports lack this vital passenger element.

Frankfurt is run by Fraport, a diversified company which manages 13 airports around the world, with a majority holding in six of them – Frankfurt and Hahn in Germany, Lima in Peru, two Bulgarian airports and one in Turkey.

Diversity is what has given Fraport steady returns: it may have lost income from airport fees due to the decrease in traffic since June 2008, but it is gaining higher revenues from its energy services and property sales.

Thus, it is non-aeronautical revenues that are becoming increasingly vital to any airport operation and it is an ability to generate good returns on these – as much as they do from aeronautical services – that makes them such a safe bet for investors in the infrastructural sector.

Slowly, airports' business models are changing. While historically they were infrastructure providers, publicly funded and exclusively focussed on the interests of the country's flag carrier, today, amid increasing privatisation in the airport sector, Europe's airports are becoming fully-fledged and diversified businesses that are self-financed.

'Their societal role and relevance has increased considerably, as they often set the agenda for local economies and communities, spreading their influence and impact on global markets,' says Robert O'Meara, communications manager of ACI Europe (Airports Council International), which represents 440 airports in 45 European countries.

Mr O'Meara argues that airports cannot sit and wait for airlines and passengers to materialise; instead they have to be pro-active network planners, seeking to attract airlines, retail, real estate, parking and consulting as this is key to fostering their competitive position and ensuring their viability.

'Charges paid by airlines do not produce high margins and they actually do not meet the cost of the infrastructure,' he says.

The new business model is also a result of the aviation liberalisation policy successfully implemented by the EU over the last two decades. It means that airlines are no longer restricted in when and where they can fly. If they are not satisfied with the performance of a route, they close it and move their aircraft to another airport.

In this sense, airports do compete with each other to attract and retain traffic. Low-cost carrier Ryanair, for example, pursues an aggressive strategy of playing airports off against one another. It has little hesitation in moving its operations when it can secure a better deal – in October it closed its Valencia base because local authority failed to provide funds for a marketing campaign.

However, the parameters on which airports compete are complex. The UK Competition Commission (CC) look likely force the British Airports Authority (BAA) to divest in several of its airports because it believes that there is a London monopoly. BAA, owned by Ferrovial, a Spanish construction company, currently owns and operates seven British airports and is faced with the possibility of having to sell London Gatwick and, in all probability, London Stansted too. However, despite the CC's intervention, would Ryanair seriously consider high-cost Heathrow as an alternative to low-cost Stansted? Or would the US carriers that took advantage of the EU-US open-skies pact to shift operations from Gatwick to Heathrow reverse the move? The CC say that it is a case of regulation attempting to even out the playing field. Unsurprisingly, BAA disagrees. 'We're effectively a regulated utility,' says Mike Forster, the company's strategy and regulation director. 'We don't support the argument they're putting forward.'

The long, not the short, of it

Airports' strategy to diversify will serve them well, but is somewhat removed from the current economic crisis. However, despite a recession looming in much of Europe, Mr Forster remains optimistic.

'It's all part of the economic cycle,' he says. 'We have found that [airport] growth is pegged a couple of points above GDP for the last 20 years so we expect our growth rates to bounce back.

'There's a dip now and for the short term and we will have a financial challenge over the coming year, but within two years it'll be back. We're quite confident that we'll move through this one.

'If you look back at significant traumas, such as 9/11, and watched the way demand has come back, there has been no seismic shift.'

Notwithstanding the current global economic downturn, airports will continue to attract investment. The intrinsic value of an airport to any country – in terms of its identity and prestige – is such that projects will never be cast aside in any investor's portfolio.

Frankfurt airport is a case in point. The German airport received government go-ahead in January 2008 for a fourth runway and third passenger terminal. It will increase runway capacity by 50 per cent and increase passenger capacity from 54m to 82m when it opens in 2011.

Table 1 – air passengers, millions

The two-year construction phase will begin in 2009 and cost some €4bn. Already, despite the economic doom and gloom, Fraport has secured 50 per cent of the financing and is confident that the figure will rise to 80 per cent next year.

'Investors are very attracted to airports because of their intrinsic growth and opportunity to develop new revenue lines,' says Colin Campbell, partner in Citi Infrastructure Investors, which manages an infrastructure fund focussed on OECD markets.

In terms of new revenue lines, Frankfurt is adding a logistics park near the new runway and already 13 hectares of that project have been leased out.

But while the appetite for long-term infrastructure projects should remain, in the short term a European and US recession will mean growth in passenger traffic – the lifeblood of any airport – stalling.

'Growth in demand shadows GDP growth but with a multiplier,' says Mr Campbell. 'That's what has happened to passenger traffic for the last 50 years. When GDP growth dips any airport will see significant negative growth in traffic of more than that multiplier.'

On a more positive note, when the economy recovers and GDP is back on track, passenger traffic not only catches up with the original trends but does so with a surge. 'One would expect to see a spike in growth when GDP recovers and a catch-up occurs for the airport,' predicts Mr Campbell. 'Economic volatility carves a shark bite out of it, but you get back to trend.'

One of the key long-term investors is pension funds, which often take a 30-year view; to them the current financial crisis is a mere blip. However, while they may not be overly concerned about the next quarter's results, the higher cost of credit will affect airports' ability to fund investment. 'They will have to pay more for that money than 18 months ago,' says Mr Campbell, 'and in terms of capital expenditure it's put up the cost of funds.'

But that shouldn't necessarily stop expansion. Any rational business would look to the timing of its investment but Mr Campbell believes that it makes no sense to slow airport development in the current economic climate: 'If you have slower traffic growth then pacing the building would make sense but it's not that controllable. Airport owners can't predict when passengers will pick up again and they see a long term positive growth curve so get on and do it. The company moves along a trajectory of charges so it's best to crack on and build.'

Power in a union

Diversification is not the only survival strategy. Collaboration is a tactic that has come under scrutiny since Amsterdam Schiphol and Paris CDG announced a long-term industrial co-operation in October 2008. This particular pairing – signed for an initial period of 12 years – comes as no surprise due to the merging in May 2004 of the French and Dutch national airlines, Air France and KLM. The airport deal, which involves an 8 per cent cross-shareholding, should deliver mutual benefits. The two have identified combined revenue and cost synergies of around €71m a year on a fullyphased basis by 2013 and expect to reduce capital expenditure by an average of €18m a year after that.

Gerlach Cerfontaine, president and CEO of Schiphol Group, said the collaborative venture 'signifies an important strategic choice for the dual-hub system in the consolidation process that is taking place in the global aviation industry. It gives Aéroports de Paris and Schiphol Group the edge over other airports and creates a leading network of connections for European and worldwide transfer travellers.

'This move is certain to improve our competitiveness... relative to our competitors in Europe and the Middle East. The strengthening of the quality of the services and our principal airport processes will offer advantages to all users of our airports – airlines and passengers alike.'

However, Chris Tarry, an aviation economist at CTAIRA, a consulting firm, believes the co-operation is not necessarily a blueprint for others to follow. 'They are two hub airports and hub airports are very vulnerable. They need different types of traffic and year-round volume. It'll be tricky for them.'

For airlines, co-operation, in the shape of mergers, acquisitions and marketing agreements, is the strategy du jour, at a time when many are looking to reduce flights. Alongside airport capacity, they have other concerns looming, such as finding funds for the EU's single European sky programme, which plans to reduce the 60 air traffic control sites in 24 European states to just one. A more unified air traffic management system will mean shorter routes, less fuel burned, less carbon emission and less cost for the airlines. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has estimated that airlines could save 10 per cent of their fuel bill. The Association of European Airlines (AEA) says that the project could pay for itself such is inefficiency in the current system.

Europe has already been carved up into functional airspace blocks (FABS) and the tenders to do the work announced, but the political will is lacking in some countries as giving up sovereign space is a sensitive subject.

There is some also debate as to whether the open skies deal between the US and EU is opportunity for airlines in the current climate. While Mr Tarry says 'it is not an opportunity in a downturn; all that happens is that capacity gets redistributed. 'BAA's Mr Forster has welcomed it and believes it will stimulate demand. 'It has meant more carriers coming here,' he says. 'Airlines have paid significant sums to buy slots to get here.' But as air ticket prices inevitably fall as new competition enters the fray, and beleaguered airlines have to absorb lower revenues, airports will gain from new carriers using their facilities.

Regulation, regulation, regulation

Ensuring that airports are run efficiently, protect users' interests and foster competition means economic regulation. There is no single economic regulatory model across Europe – there is only consensus that it would be impossible to create one. While in some countries, such as Sweden, Denmark and Austria incentive regulation prevails – most commonly using price caps – elsewhere, as in the UK, Netherlands, Spain and Portugal, rateof- return regulation (RoR), is the norm. This demands that airports charge a rate commensurate to what would be acceptable in a competitive market. At the big three UK airports that are price controlled – Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted – the regulator indirectly underwrites the capital expenditure programme and awards a rate of return. Although this is sometimes dressed up as incentive regulation, the airport operator's ability to outperform can often be marginal.

As a regulated utility, airports have no opportunity to charge more – in a downturn or at any other time. What they can do is earn more revenue from shopping, eating and drinking at airports, something that causes unease with their airline customers.

Airlines have long believed that airports put profits before passengers, filling concourses with shops, restaurants and bars rather than concentrating on the punctuality of flight departures and speed of clearing security. 'Airports haven't done a lot to help themselves,' says Mr Campbell. 'There's a sense that airports are out of touch and working against the interest of their customers.'

But ACI Europe points out that the real threat for airports comes from governments looking to aviation to plug holes in treasury accounts. In October, both the Belgian and Irish governments announced that they would be introducing an air passenger tax, although the Belgian government subsequently announced a u-turn. Airport operators' concern is that such interim taxes will reduce their competitiveness.

Ownership structures also differ across Europe. Historically, airports have been in the hands of the public sector (either at state or local level) and often dominated by the flag-carrier airline, but this is changing. Governments are no longer willing to finance such large scale and long-term airport infrastructure projects.

Nonetheless, the political will in any infrastructural development cannot be overlooked. Growth depends on simple things such as planning permission and whether the country has a planning system that allows long-term decisions to be made efficiently and effectively – the 18-year wait to see Terminal 5 (T5) open at London Heathrow is testament to that. It took 10 years alone for the planning application to go through. 'Regulation is at the bottom of this [delay] and it hasn't worked well enough' said Sean Horkan, investment strategy director for BAA London Heathrow.

One glimmer of hope is the establishment in June 2007 of the EU Observatory, a consultative body on airport capacity, attempting to guide and advise the policymakers inside the EU on a pan-European level. It has no authoritative role but industry observers welcome the fact that it will have a pan-European voice. It brings together the EU, Eurocontrol, national authorities, stakeholders and industry representation such as ACI Europe.

ACI Europe's director general, Olivier Jankovec, believes the Observatory is a step in the right direction. 'The EU can no longer afford to ignore the extensive economic and environmental risks linked to airport congestion,' he says. 'We need to monitor airport capacity on an ongoing basis and consider the performance of the European aviation network as a whole.'

Crunch time?

Eurocontrol predicts that by 2030, 2.5m flights will remain unaccommodated due to a lack of adequate airport capacity in Europe, with close to 20 airports totally saturated and 170m passengers affected. Lack of capacity is the greatest threat to airports and it stands to dent the region's position on the world stage.

Air space is being tripled between now and 2020 – chiefly through better air traffic management based on the single European sky – and airport capacity needs to keep pace with that. While space is being boosted in the air, it is not reflected on the ground and an airport capacity crunch is feared.

Aviation's inclusion in the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), a cap and trade system that limits the amount of environmental pollution industries are allowed to emit, threatens a further impact on these capacity demands, unless the EU follows a policy that reconciles growth with environmental objectives. 'It will add cost and slow the recovery' reckons CTAIRA's Mr Tarry. The European Regions Airline Association (ERA) estimates that it will cost airlines €3.5bn in the first year; airlines are in no fit state to invest in more fuel-efficient aircraft.

The UK government's stated aim of providing additional capacity, which is the basis of the CC's conclusion on BAA, is being offset by its approach to emissions trading and air passenger duty tax – both of which raise the cost of travel to the consumer.

Just how worrying the capacity issue is can be demonstrated by Heathrow's T5 opening in March 2008. Despite this expansion, it is still operating at 99 per cent capacity, while its continental European rivals are in much better shape – for example Amsterdam Schiphol is operating at 73 per cent capacity, Paris CDG at 76 per cent.

Table 2 – largest European airports, 2007

To further compound Heathrow's problem, Europe's busiest airport also has the least space to expand. Paris CDG has three times the land area of Heathrow and already operates from four runways; Madrid has ample land availability; and Schiphol operates with five runways, although some have restrictions for noise considerations. Frankfurt, as previously mentioned, will have eased its capacity issues by 2011.

Heathrow's two runways are not enough to cope with future demand and it urgently requires a third runway to maintain its world position. A decision on whether Heathrow can build one will be announced in December 2008. If it does get the go-ahead, the plan is to open a third runway by 2020 to the north of the airport, although strict environmental restrictions laid down by the British government will shape, influence – and no doubt delay – this expansion.

'We see the provision of extra capacity as fundamental to keep Heathrow competitive,' says BAA's Mr Forster. 'If we don't, other European hubs will become more attractive.'

And it isn't just Europe that Heathrow will have to keep at bay. 'We're seeing Dubai increasingly as competitor, as well as Schiphol, Frankfurt and Paris CDG,' he says.

'The investment in expansion seems very large but we're not being held up by investment, there is no shortage of money; it's political will and the approval mechanism.'

Elsewhere around the world, it is a different picture: airports generally seem to have few growth constraints. This is probably best exemplified in China, where some 97 airports are on the drawing board.

However, it is airlines and airport hubs in the Middle East that European airports fear most. They benefit from proactive, integrated aviation policies and have been quick to offer passengers flying from Europe to Asia, or between Asia and the Americas, alternative transfer points to Europe's major hubs.

Table 3 – miscellaneous other airports, 2007

Just compare Heathrow's T5 opening with the new airport project in Dubai. T5 was one of the largest airport expansion projects in Europe in recent years, yet it is dwarfed by Dubai, where the new Terminal 3 is twice the size of T5. Even so, there is a completely new Dubai airport under construction and scheduled to begin operations next year that will become the world's largest airport. It will have six runways and an eventual capacity of 120m passengers a year, almost 80 per cent more than the current passenger traffic of Heathrow and three times Heathrow's runway capacity.

'Clearly, other world regions recognise the key role of airports and global connectivity in fostering the long-term economic growth of their regions and are investing accordingly,' says a rueful Mr O'Meara.

Air Berlin case study

View from the sky: an airline's perspective

Joachim Hunold, CEO of German carrier Air Berlin, assesses the state of Europe's aviation sector.

Do you think airports will try and squeeze more money out of airlines in order to compensate for their reduced income?

Yes, that is borne out by the facts. In most cases the airports in Germany are passing on cost increases to the airlines, even though the airlines, by increasing the number of passengers they carry, also generate growth in traffic and turnover. Airport charges were increased for us as well, even though Air Berlin has achieved a continual increase in passenger figures each year. One reason for this is that most German airports are publicly owned. The German federal states act as majority shareholders, and as such they can raise their revenue in the short term by increasing charges. In the end, though, it is not just the passengers who suffer as a result of having to pay for the cost increase, but the federal states as well. Fewer passengers because fares are too expensive will also mean lower tax revenue and therefore less money flowing into state coffers in the long term.

What effect has the downturn and the price of oil had on Air Berlin's profitability?

The global downturn and the continuing financial crisis have had an adverse effect on the entire world economy. Especially energy-intensive industries, such as aviation, have suffered disproportionate financial pressures on account of the enormous rise in the price of oil.

However, Air Berlin has been able to maintain its position during this worldwide crisis that is affecting our industry. We reacted to the macroeconomic situation much earlier than any other airline by implementing a comprehensive efficiency programme and proved that we are flexible and adaptable and that we can respond to demand. Furthermore we are constantly working on our productivity, on fuel-saving measures and on reducing external costs. As a result, Air Berlin was able to show a respectable result at the end of August when fuel prices reached an all-time high and to increase its turnover in the second quarter of 2008 by 6.7 per cent from €815m to €870m. Given current conditions, we are expecting to achieve an operating profit in 2008.

How will environmental concerns impact on your need to increase your route network and grow your business?

Air Berlin is the airline that has achieved the fastest growth since German reunification and is now the fourth largest airline in terms of European traffic. In 2007 alone we carried about 28m passengers, and since taking over LTU in the same year, we also offer intercontinental flights.

At Air Berlin growth and environmental awareness go hand in hand. The best example is our investment in a state-of-the-art, low-emissions fleet – that is environmental awareness par excellence, and all without any legal obligations. Air Berlin's fleet, for instance, has an average age of 5.2 years, which makes it one of the youngest in the industry. When Air Berlin placed an order for 50 Boeing 787 long-range airliners with a value of €4bn in July 2007, it again strengthened its claim to making growth as environmentally compatible as possible.

What effect will new regulatory and legal pressures, such as open skies or the emissions trading scheme, have?

We are in a situation of pro-cyclic policies, in other words, where the political measures are exacerbating crises instead of reducing the pressures on our industry. Under the cloak of conservation politicians are constantly thinking up new laws that make air transport more difficult or prevent it altogether. That is despite the fact that the airline industry is coming up with numerous initiatives, both in terms of technical improvements to the aircraft and in terms of optimising operational procedures.

The emissions trading scheme, as currently envisaged, will further reduce the competitiveness of European airlines. Emissions are a global problem, and one that also requires a global solution. This is the only way in which emissions trading can act as a suitable incentive to reducing CO2 emissions. The problem is that if aviation is only covered by the ETS in Europe, the effects for climate protection will be marginal. There is also a threat of massive competitive distortion. That is why Air Berlin is working hard on international committees to promote a global emissions trade for aviation.

At the same time the single European sky that was already being planned 10 years ago could save up to 500,000 litres of fuel a day, as well as the associated volume of CO2 emissions; nevertheless, it is unlikely to be implemented before 2018. That, of course, is far too late. That is why we are expressly in favour of giving priority to the single European sky rather than implementation of the ETS.

Is an airline still an attractive proposition to investors? Isn't it too risky now?

We are of the opinion that Air Berlin remains an attractive investment. The relevant question for investors is rather 'if not now, when'? We will see a recovery in the long run, which means that those airlines that do their homework, such as Air Berlin, come through the crisis successfully and will most likely benefit from a consolidation in the airline market. Thus, investors will get an appropriate return on their money.

To read the original document on the Freshfields website here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.