The European Union's new screening tool for third-country subsidies introduces a novel form of mergers & acquisitions scrutiny. Companies worldwide need to account for timing and execution risks arising from this system when M&A deals involve businesses with activities in the EU.

The EU's Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) applies to deals agreed after 12 July 2023, and the European Commission (EC) now has the power to ex officio investigate potentially distortive subsidies granted by third countries. The FSR takes full effect on 12 October 2023, when certain M&A deals must be notified, reviewed and cleared before they can be consummated.

Like familiar systems of premerger control, the FSR establishes mandatory notification requirements, backed by standstill obligations, and compliance is subject to potentially severe financial penalties. Notwithstanding the fact that the final Implementing Regulation (FSR-IR) streamlined the requirements of notification – consistent with overwhelming consultation feedback – the reporting burden on firms will be significant. Compliance with the FSR should therefore form an early and integral part of M&A transaction planning.

What's the purpose of the new system?

The goal of the FSR is to 'level the playing field' with respect to unfair advantages that third-country (non-EU) government subsidies may cause in the context of M&A deals. A simple example would be an acquirer outbidding rivals in a controlled M&A auction by offering a superior acquisition price supported by state-backed financing that does not reflect market terms. But the notion of a subsidy is broad, and many more nuanced scenarios also are in scope. The FSR is relevant to all companies that are active in the EU – not only state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or firms that have benefited from substantial direct third-country support. EU-based firms also are affected, to the extent that they (or subsidiaries anywhere in the world) have obtained foreign subsidies.

As a matter of course, the EC must authorize all state aids by EU Member States before such schemes are put into effect. The EU clearly does not have the same powers with respect to schemes outside the EU, but the FSR aims to address competitive distortions, within the EU's internal market, of such foreign subsidies. That is a tall order, especially in the present economic climate, when governments worldwide (including major EU trade partners) are introducing lavish support schemes for key sectors, such as energy, transport and technology.

The FSR supplements – and will be applied in parallel to – the EU's existing regulatory toolbox for M&A and competition scrutiny, including merger control and foreign direct investment, as well as EU rules on state aid and public procurement. The FSR also includes specific rules for participation in public procurement tenders.

What deals are in scope for review?

The transaction types that are in scope are the same as for the EU Merger Regulation – 'concentrations' – essentially acquisitions of control, mergers and the creation of full-function joint ventures.

Such transactions must be notified to the EC for prior approval when two thresholds are satisfied:

- EU-wide turnover exceeding 500 million euros, in the most recent financial year, that is attributable to the target being acquired, one of the merging parties or the joint venture.

- Third-country financial contributions exceeding 50 million euros, in the three years preceding the deal, that are awarded to the transaction parties, taken together.

The notion of a 'financial contribution' is key, but it is not comprehensively defined. The FSR gives examples of certain categories of contributions: the transfer of funds or liabilities, foregoing of revenues otherwise due, and the provision of goods or services – to name a few – where the benefit was provided by a third-country government or entity. This is a broad notion indeed, and all contributions received by the parties should be considered, even though they may not have been tracked in the ordinary course of business.

Beyond the specified notification requirements, the EC may also launch an ex officio investigation, if it considers that a foreign subsidy – irrespective of its value – could distort competition in the EU.

What does the review involve?

A transaction that is notifiable under the FSR is subject to a standstill obligation, such that it cannot close unless and until the EC clears the deal. The maximum penalty, in case of failure to comply with that obligation, is a fine of up to 10% of the firm's aggregate turnover in the preceding financial year.

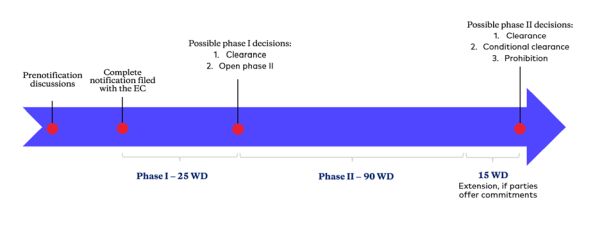

The review process and timeline align generally with the EU Merger Regulation: An initial phase I review of 25 working days (WDs) that may be followed by an in-depth phase II review of 90 –105 WDs. The review may be suspended if the parties fail to respond fully to an information request. A notable difference, compared to the merger review process, is that any remedy commitments are formally addressed only in phase II.

Parties are encouraged to engage early on in confidential prenotification discussions with the EC to ensure that the submission of the filing is deemed complete as promptly as possible in order for the clock to start. The EC may request additional information during the review. Prenotification contacts also are the appropriate forum to discuss any waivers with respect to information to be included in the filing.

A designated notification form (Form FS-CO) specifies the information to be provided on the parties, the transaction and the relevant financial contributions, as well as an analysis of their impact. As with respect to notifications under the EU Merger Regulation, many transaction-specific and internal business documents also are to be annexed.

Different levels of detail are required for different categories of third-country financial contributions. Extensive information is to be included in respect of any contributions categorized among those deemed 'most likely to be distortive' (see below), with a view to focus resources on areas of potential concern. Other financial contributions are subject to a lesser reporting burden.

When is a third-country subsidy problematic – and is there a fix?

As mentioned, the jurisdictional and notification requirements reference third-country financial contributions. But the actual review concerns 'subsidies', meaning financial contributions by a third country that, directly or indirectly, confer benefits on a party conducting business in the EU and are selective in the sense that they are limited as to the number of beneficiaries or industries. This is a broad notion.

A foreign subsidy is deemed to be distortive of the EU's internal market if it is 'liable to improve the competitive position of an undertaking in the internal market, and where, in doing so, that foreign subsidy actually or potentially negatively affects competition'.

This assessment depends on several factors, including the subsidy's amount, nature, purpose and any conditions attached to it. The following rules of thumb can be discerned:

Naturally, factors pertaining to the beneficiary's situation also are important, including the competitive landscape of the markets, the sectors involved, and the nature and degree of the beneficiary's presence in the EU.

The assessment ultimately involves a balancing test between, on the one hand, the competitive advantage conferred by any distortion caused by the subsidy and, on the other hand, any positive effects for the relevant subsidized economic activity, as well as broader policy considerations.

The parties may propose remedies to address any actual or potential distortions arising from foreign subsidies, but formal offers may only be put forward during an in-depth review. Any remedies should be tailored to the harm and may, for instance, involve:

- Foreign subsidy repayment.

- Corporate governance commitments.

- Access or licensing commitments.

- Capacity or market presence reductions.

- Investment restraints.

- Divestment commitments.

- Dissolution of concentration.

The EC may decide to accept remedies that parties propose, but it also may impose other redressive measures that it deems necessary and proportionate to remedy the distortion fully and effectively.

Takeaways for dealmakers

The new FSR adds complexity – for sellers and buyers alike – in devising regulatory strategies for M&A deals. Immediate points of note are that:

- The FSR applies to deals agreed after 12 July 2023, and notifications are required for deals that close after 12 October 2023, if jurisdictional thresholds are satisfied.

- The pre-transaction diligence requirements flowing from the FSR

can be quite cumbersome. Given their relevance during transaction

negotiations, buyers and sellers will optimize negotiation

positions by advance preparation. By way of example:

- Companies need a system to track financial contributions and subsidies. In an acquisition, information concerning all third-country financial contributions that a member of the acquirer's and target's respective corporate groups obtained three years prior to a transaction. That information would be necessary – in addition to more readily available turnover data – to determine whether the transaction meets the mandatory FSR notification requirements.

- Where the acquisition triggers an FSR notification, the buyer and seller will need to ensure that the transaction documentation accounts for the timing and execution risks that follow from the EC's mandatory review – in addition to any reviews under merger control and foreign investment rules.

- Any such risk arising from FSR review depends on whether the third-country financial contributions amount to foreign subsidies that distort the internal market. By undertaking a comprehensive feasibility analysis, the transaction parties can draw the necessary documentation consequences for transaction risk, cooperation and timing. Potential beneficiaries of subsidies may do the same individually to assess FSR risk in M&A settings.

- Regulatory strategies also should include proactive engagement with the EC, as in merger review, in confidential prenotification contacts. Given the novelties of the FSR review system, it is imperative to allow for such discussions when deals qualify for review. Importantly, notwithstanding such contacts, the EC will not accept formal filings for any deals prior to 12 October 2023, which means that qualifying deals agreed between 12 July 2023 and that date realistically cannot close before late November.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.