Co-authored by Nathaniel E. Castellano

Originally published by Aerospace & Defense Law360, Government Contracts Law360, and International Trade Law360 on April 14, 2016

Government contractors interested in pursuing international sales should also consider the potential availability of foreign military funding (FMF) to their foreign government customers for the lease of defense equipment. Although typically prohibited,[1] in some circumstances, the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) has approved the use of FMF funding for equipment leases. As explained below, using FMF funds to facilitate leases of defense equipment can be advantageous to American defense contractors, foreign government customers and the U.S. government. Contractors may be in a position to self-finance these leases, or they may require third-party financing. For the latter, executing these deals will require combining the worlds of FMF transactions and commercial equipment lease financing, which at first blush present mutually conflicting requirements.

The Case For FMF Leasing

With the decline in U.S. defense spending, American contractors are looking abroad to sell their goods and services to foreign customers. At the same time, increasingly unstable geopolitical conditions and rapid growth in emerging economies make some foreign governments eager customers for U.S.-produced defense equipment. Under certain circumstances, the U.S. government facilitates and funds the sale of military supplies and services to friendly countries.

Often, the U.S. government will assist in funding these transactions to further foreign policy and military objectives. The sale of defense equipment to foreign customers generally occurs within the legal framework of either a (1) foreign mlitary sale (FMS) or (2) direct commercial contract (DCC) with a foreign government, assisted with FMF funds.

FMS, which is the more common of the two approaches, involves a foreign government purchasing directly from a U.S. defense agency, with the defense agency contracting through a standard federal government supply contract with a U.S. contractor. The U.S. Department of Defense handles all aspects of the procurement — including contract formation and administration, selection of terms and conditions, quality assurance, payment, and dispute resolution. This relieves the foreign government of a considerable administrative burden, and allows it to capitalize on the DOD's acquisition experience. Conversely, the foreign customer loses some control over the acquisition process and may pay a premium for the DOD's services.

Under the DCC framework, the foreign customer contracts directly with a U.S. contractor. The U.S. government may provide assistance in the form of FMF. In contrast to the FMS framework, in a DCC, there is privity between the contractor and the foreign government. Although various requirements are imposed by the U.S. government, the foreign government and the contractor act relatively independently during the acquisition process. The prerequisites for entering a DCC and obtaining FMF funding are set forth in DCSA guidance,[2] which requires, among other things, that the contractor execute a contractor certification and agreement with DSCA and, potentially, submit to a pre-award survey, pricing review and U.S. government audit rights.[3]

FMS and FMF transactions are typically contracts for sale, but they can also be structured as leasing arrangements. Foreign governments might prefer leases because leasing may involve lower cost and less risk of owning equipment that could become obsolete. As in any equipment lease, the lessee pays for the value it uses. From the U.S. government perspective, the U.S. Department of State and the DOD are incentivized to approve FMF for leases, because such arrangements allow leverage of increasingly scarce appropriations and facilitate relations with allies. Leases appeal to contractors, because they generate increased revenue and may ultimately result in the foreign customer purchasing the equipment (e.g., through a lease-to-own provision). Even without a sale, the contractor may be able to re-lease or resell the equipment.

The FMS legal framework expressly allows for leases under certain circumstances, but leases generally have been prohibited from receiving FMF funding.[4] Foreign customers may nevertheless prefer direct lease contracts supported by FMF, so that they have more control over the transaction and can obtain equipment that they otherwise may not have funding to procure. The DSCA, in limited circumstances thus far, has shown a willingness to consider FMF for lease transactions. Unlike FMS leasing, which is more common, there are no guidelines for FMF leases, and striking the balance between a compliant FMF transaction and a commercial equipment lease can be difficult. The following section addresses issues that must be considered when contemplating an FMF lease.

Structuring an FMF Lease

Several variables must be addressed on a case-by-case basis when structuring each FMF lease transaction. The following elements are likely to be key considerations in any FMF lease.

1. The contractor may need third-party financing.

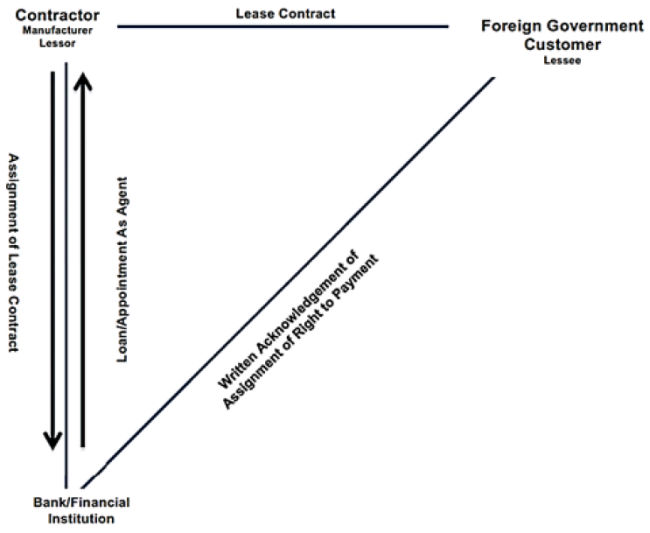

While the largest defense contractors may be sufficiently capitalized to self-finance the lease of military equipment, some contractors may need to secure financing through a commercial financing institution. Certain standard market lease terms are generally necessary for an equipment lease to be financeable through the commercial markets. For example, the contractor/lessor will need to assign the lease and transfer title to the leased equipment to the financing entity. The contractor will remain responsible for all performance obligations in the lease, but the financing entity will be assigned the right to receive lease payments. The structure of the transaction may be diagramed as follows.

Figure 1

In other transactions, the contractor/lessor may also need to utilize a lease finance company or broker as an intermediary between itself and the financing institution. The additional steps in this transaction are identified in the following:

Figure 2

In both situations, the contractor will be appointed as the agent of the financing institution for performance of the lease obligations.

2. The third-party financing entity will likely demand terms and conditions commensurate with standard commercial equipment leases — e.g., a hell or high water provision.

A standard term in commercial equipment leasing is the "hell or high water" provision, which binds the lessee to pay a specified, periodic rate throughout the lease, regardless of the parties' other obligations. Financial institutions involved in financing U.S. government contracts understand that U.S. government lease contracts will not include a "hell or high water" provision due to, among other reasons, the "termination for convenience" clause. Some financing institutions will accept an assignment of the right to payment from the U.S. government customer, but may be less willing to accept such an arrangement with a foreign government customer. Financing institutions may demand a "hell or high water" provision for a lease contract with a foreign government.

3. The parties will have different interests concerning transfer of title.

Financing agencies will likely require transfer of title, which is a standard commercial condition. Also, the contractor may want to transfer title so it can book the revenue from the sale. For its part, the foreign government customer may want to ensure that the contractor/manufacturer has the right to lease and, if it so chooses, sell the equipment under the terms of an option to purchase. All of these rights and obligations will need to be addressed in the deal documents executed by the various parties.

4. The foreign government customer and the U.S. government will require privity of contract between the contractor and the foreign government.

Even though title to the leased equipment and the right to receive payment will be transferred to a third-party financing entity, an FMF lease will need to be structured to maintain privity between the U.S. contractor and the foreign customer. First, as a matter of U.S. law, FMF transactions must occur between an approved foreign government and a U.S. contractor, which must be the manufacturer of, or add value to, the goods sold.[5] Second, the foreign customer will often demand that it have privity with and enforceable contract rights against the contractor/lessor to ensure that the leased equipment is delivered, reviewed and maintained and meets its requirements. Indeed, the foreign government customer may demand that it interact exclusively with the contractor and that the financing arrangements be opaque as to its contractual rights and obligations.

Conclusion

There are many advantages to FMF leasing. Despite its historic prohibition, the DSCA may, in some circumstances, be persuaded that the lease arrangement is in the best interests of both the foreign government customer and the U.S. government. To take advantage of the opportunities FMF leasing provides, contractors will need to address generally applicable market terms and conditions and conform the various deal documents to requirements imposed by the U.S. government, the foreign government customer, and the financing entity. This is feasible if all parties to the deal are willing to consider the legal and commercial market constraints imposed on the others in drafting and negotiating the documents.

[1] The Arms Export Control Act (AECA) allows the president to lease DoD defense articles to eligible foreign countries or international organizations for a period not to exceed five years and a specified period of time required to complete major refurbishment prior to delivery. 22 U.S.C. § 2796 There must be compelling foreign policy and national security reasons for providing such articles on a lease basis, and the articles must not be needed for public use at the time. Id. This authority is delegated to the director of DCSA. Leases are permitted using FMS funding, ESAMM § C.11.6, but FMF funds are generally prohibited for the lease of defense articles. Id. at C.9.7.2.9.6, Table C9.T10 (listing "lease of defense article" as an item that should not be purchased with FMF), at http://www.samm.dsca.mil/listing/chapters.

[2] DCSA, Guidelines for Foreign Military Financing of Direct Commercial Contracts (August 2009), at http://www.dsca.mil/sites/default/files/2009_guidelines_for_fmf_of_dccs_0.pdf

[3] Id. at 8, 11, 12, 13, 19.

[4] See supra note 1.

[5] DCSA, Guidelines for Foreign Military Financing of Direct Commercial Contracts, supra note 2, at 1.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.