This is part of a series of articles discussing recent orders of interest issued in patent cases by the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

In Enanta Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Pfizer, Inc., No. 1:22-cv-10967, Magistrate Judge Boal granted in part Pfizer's motion to compel and denied Enanta's motion to compel, both of which had been referred by Judge Casper.

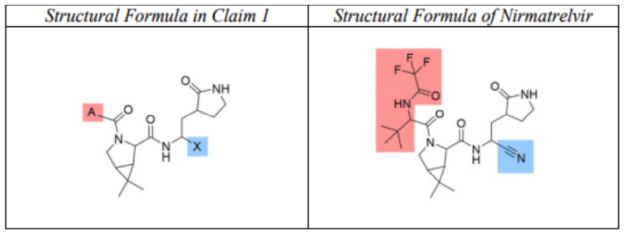

Enanta asserts that the group shaded in red is an "optionally substituted C1-C8 alkyl" as used in the claims:

The Parties agreed that:

The term "optionally substituted" means that the referenced group may be unsubstituted (no substituents) or substituted, including with one or more additional groups individually and independently selected from groups described herein.

Pfizer moved to compel supplemental infringement contentions and a more substantive response to its interrogatory inquiring why Enanta asserts that the group in red qualifies as an "optionally substituted C1-C8 alkyl."

Enanta moved to compel a more fulsome response to its interrogatory inquiring why Pfizer disputes the claim mapping, which Pfizer claimed it was unable to answer without first understanding Enanta's affirmative theory.

The Court first found that Enanta's infringement contentions were sufficient because they mapped the elements of the claims to the accused chemical structure, and debates about the merits of that mapping are beyond the scope of such contentions.

The Court next found that Enanta's response to Pfizer's contention interrogatory was lacking, as it does not explain why the group shaded in red can qualify as "optionally substituted" where it is not one of the specifically enumerated groups referenced by the Parties' agreed definition of the term.

Last, the Court found that Pfizer's interrogatory response was sufficient, as Enanta bears the burden of showing infringement and Pfizer is unable to explain why it disagrees with an infringement theory that has not yet been sufficiently articulated.

Thus, the Court granted Pfizer's motion to compel a further response to its interrogatory seeking to understand Enanta's infringement theory, and otherwise denied the Parties' motions to compel.

In Cozy, Inc. v. Dorel Juvenile Group, Inc., No. 21-10134, Magistrate Judge Dein allowed Dorel's Motion for Summary Determination of Priority Dates for Asserted Patents.

Cozy sued Dorel alleging infringement of four patents: U.S. Patent Nos. 9,902,298 (the "'298 Patent"), 9,669,739 (the "'739 Patent"), 7,156,416 (the "'416 Patent") and 8,136,835 (the "'835 Patent"). Dorel sought summary judgment of the priority dates for those four patents. Specifically, Dorel sought determinations that:

- the '298 and '739 patents were only entitled to priority to their application filing dates due to a break in the priority chain; and

- the '416 and '835 patents were only entitled to claim priority to September 24, 1997, based on inventor Arjuna Rajasingham's original claim of priority.

Cozy, in response, argued that all four patents were entitled to a priority date of November 8, 1999, based on later filings by Dr. Rajasingham, and argued that disputed facts warranted denial of the motion.

The '298 and '739 Patents

Regarding the '298 and '739 patents, the issue was whether the patents complied with 35 U.S.C. § 120's requirement that to claim priority from an earlier application, the earlier application and each intervening application must provide written description support for later patent claim.

Dorel argued that one patent in the priority chain, No. 9,150,127 ("the '127 patent"), shared no common subject matter with the '298 and '739 patents and so broke continuity for purposes of written description and that the '298 and '739 patents should have priority dates corresponding to their application filing dates of January 20, 2015 and September 9, 2015, respectively.

The '298 patent relates to "[a] system of air cushions to protect during impact, an occupant in a vehicle seat comprising elements for protection of the head and neck," while the '739 patent relates to "[a]n arrangement in passenger vehicles, that diverts the impact energy in lateral or side impacts away from the passengers to the remaining mass of the vehicle."

Cozy offered three arguments as to why Dorel's motion for summary judgment should be denied. First, Cozy argued that the issue could not be resolved as a matter of law, because it would require a "a substantive, fact-intensive written description analysis." Second, Cozy argued the '127 patent incorporated by reference U.S. Patent Application No. 11/113,028 (the "'028 Application"), which maintained priority to the parent of the priority chain, U.S. Patent Application No. 09/435,830, (the "'830 application"). Third, Cozy argued the motion should be dismissed because Dorel failed to address other chains of priority for the '298 and '739 patents.

The Court rejected all three of Cozy's arguments.

1. The '127 Patent Had No Overlap with the '298 and '739 Patents

First, the Court agreed with Dorel that the '127 patent had "virtually no overlap" with the '298 and '739 patents. Cozy, relying on its expert's declaration, argued that the "airbag" recited in the claims of the '298 and '739 patents was equivalent to the "'anatomical cushion' and 'pillow pad'" claimed in the '127 patent. The Court found this to be a "contorted interpretation" of the '127 patent, which according to the Court was in conflict with the Court's prior ruling on claim construction. Therefore, no "substantive, fact-intensive analysis" was needed, because the material facts were undisputed, and the question of continuity of disclosure in a patent chain was a question of law. The Court held that "no POSA could reasonably conclude that the ['127 patent's application] contained 'an equivalent description of the claimed subject matter' of the '298 and '739 Patents," and thus, the '127 patent did not meet the description requirement of § 112(a) to provide a basis for priority to the '298 and '739 patents.

2. There Was No Incorporation by Reference

Second, the Court found that, as an undisputed fact, the '127 patent did not incorporate by reference the '028 application or the '830 application. The '127 patent, during prosecution and at the time its application published, did incorporate by reference the '028 patent. However, the Examiner deleted the reference before the patent issued. The Court held that the issued patent, lacking a reference to the '028 patent, did not provide written description support for the '298 and '739 patents.

3. Cozy Could Not Claim Other Priority Chains to 1999

Third, the Court held that Cozy could not claim other priority chains, specifically rejecting Cozy's attempts to rely on priority chains neither reflected on the face of the patents nor in Cozy's interrogatory responses.

As Cozy failed to demonstrate that the '298 and '739 patents had an unbroken priority chain, the Court held that each was only entitled to its application date.

'416 and '835 Patents

Dorel also challenged that the '416 and '835 patents, as a matter of law, claim priority to September 24, 1997 as originally claimed in their applications. Dr. Rajasingham had attempted to amend the filings to claim priority to November 8, 1999, instead, but Dorel argued the attempt was unsuccessful. Both patents were subject to multiple Requests for Certificate of Correction, and the parties disagreed on the relevance of the prosecution and post issuance filings for each patent.

1. The '416 Patent

During prosecution of the '416 patent Dr. Rajasingham repeatedly argued that references from 1998 and 2000 should not be considered prior art because his applications claimed priority to September 24, 1997. When the '416 patent issued, the text described it as a divisional of an application filed in 1999 and stated that it claimed priority to an application filed in 1997.

After the patent issued in 2007, Dr. Rajasingham submitted two Requests for Certificate of Correction. The first was granted in 2012 and added two pages of text referencing multiple chains of priority to 1997 to the '416 patent's text.

The second Request for Certificate of Correction was submitted in 2016 and attempted to correct the priority claim to 1999. The Court found it remarkable that in this filing Dr. Rajasingham did not refer to the 2012 Certificate of Correction, nor did he indicate that he had previously relied on the 1997 priority date to overcome asserted prior art. The second request for correction was denied as moot by the PTO.

Cozy argued the rejection of the 2016 Request for Certificate of Correction demonstrated that the patent claimed priority to 1999, because the PTO already believed the patent claimed priority to 1999. However, the Court noted that neither the 2016 request itself, nor the documents the PTO considered, referenced the 2012 correction or the 1997 priority claim, and so the Court held that the denial of the 2016 Request for Correction did not support the priority claim to 1999.

Therefore, the Court allowed Dorel's motion for summary judgment, holding the '416 patent claimed priority to September 24, 1997.

2. The '835 Patent

The text of the '835 patent's application stated it was a divisional of an application filed in 2005, and listed multiple applications from which it claimed priority, including one filed September 24, 1997.

During prosecution of the '835 patent, the Examiner first rejected the claims based on prior art from 1999 and 2000. Cozy overcame those rejections with arguments, but never contested that the references from 1999 and 2000 were prior art. The Examiner issued subsequent office actions rejecting some of the claims in light of references from 2003 and 2008. Cozy amended the claims to overcome the rejections, and again did not allege that the references were not prior art.

After the '835 patent issued in 2012, Dr. Rajasingham filed a Request for Certificate of Correction, attempting to insert two full pages of text, listing additional applications to incorporate by reference and claim priority to. The PTO allowed the request and issued a Certificate of Correction. The amended text included many priority claims, several of which dated back to 1997.

In 2017, Cozy submitted an additional Request for Certificate of Correction, attempting to amend the priority claim to 1999, without striking any of the original patent text or the text amended into the patent by the 2012 Certificate of Correction. The PTO allowed the correction, consisting only of the requested amendments.

Dorel argued the priority date for the '835 patent was September 24, 1997, as stated in the original application and in the first Certificate of Correction in 2012. Dorel further argues that the 2017 Certificate of Correction that was granted by the PTO was ineffective because Dr. Rajasingham failed to delete the existing priority claims to 1997 or put the PTO on notice that he was deleting the claims.

Cozy argued that the 2017 Certificate of Correction was issued and edited the "exact same" section of the patent as the 2012 correction. Cozy argued that, even without specifically striking language from the 2012 correction, the 2017 Certificate of Correction should govern when any inconsistencies exist, giving the '835 patent a valid claim of priority only to 1999.

The Court held that the priority claim to 1997 contained in the 2012 Certificate of Correction was never disclaimed, and was thus still effective. Accordingly, the Court allowed Dorel's motion for summary judgement, holding the '835 patent claimed priority to September 24, 1997.

In Gratuity Solutions, LLC et. al. v. Toast, Inc., No. 22-11539, Judge Saris allowed in part and denied in part Toast's Motion to Dismiss and allowed Toast's Motion to Strike Gratuity's expert declaration.

Gratuity develops, commercializes, and sells a gratuity distribution and management software to hospitality businesses. Toast offers point of sale, operations, and financial technology solutions to restaurants. Gratuity and Toast entered into two non-disclosure agreements, first in 2016 while Toast considered using Gratuity's software, and later in 2019 when Toast considered acquiring Gratuity altogether. In 2021, Toast launched a new gratuity management software.

Gratuity sued Toast on three counts. Counts I and II alleged infringement of two U.S. Patents. Count III alleged Toast breached the two non-disclosure agreements.

Toast moved to dismiss Counts I and II on the grounds that both patents-in-suit involve patent-ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101, and moved to dismiss Count III on the grounds that Gratuity failed to plausibly allege a breach of contract claim. Toast also moved to strike an expert declaration that Gratuity submitted and cited to in their opposition to the motion to dismiss.

Motion to Strike

The Court first addressed the motion to strike. Gratuity submitted an expert declaration with their opposition brief, discussing whether the claims at issue were technical improvements over the prior art.

Toast argued that such a declaration was improper at the motion to dismiss stage, and that the declaration contained improper legal conclusions. Gratuity urged the Court to convert the motion to dismiss into a motion for summary judgment and consider the expert's declaration.

The Court declined to consider the expert declaration because it was not part of the pleadings. The Court noted that unlike the patents or the prosecution history, which are considered at the motion to dismiss stage, the declaration is not a public record. Furthermore, patent eligibility under § 101 is a matter of law, which the Court could decide without relying on the expert declaration. Therefore, the Court allowed Toast's Motion to Strike.

Motion to Dismiss Counts I and II (Patent Infringement)

Toast moved to dismiss the two counts of patent infringement, asserting that both patents were directed to patent ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101. Gratuity disputed this assertion, arguing that the claims "bring together numerous unconventional concepts and features in a system that offers tangible improvements."

Both patents-in-suit are titled "System and Method for Managing Gratuities" and are directed to "managing gratuities, and more particularly to calculating, allocating, and distributing gratuities among service employees."

The Court considered both patents under the Alice/Mayo framework. At step one of the Alice test, the Court held the claims were directed to the abstract idea of "extracting, receiving, and storing of transaction and employee information . . . followed by the executing of gratuity distribution rules and returning of gratuity allocations to client business systems." The Court noted that those steps are directed to "the collection, analysis, and display of available information in a particular field" which the Federal Circuit has previously held to be a patent ineligible abstract idea.

Under step two of the Alice test, the Court held that Gratuity had sufficiently pled that the claims of one – and only one – of the asserted patents contain an additional inventive concept. Specifically, the relevant claim is to "a cloud computing [gratuity management] system remote from the plurality of client business systems" that performs the necessary calculations "on remote servers using data received from local systems," which enables the execution of "gratuity distribution calculations without additional on-site hardware."

The Court ruled that these claim elements "plausibly improve[] computer functionality by 'offload[ing] the computationally intensive tasks from local, legacy hardware into the cloud.'"

As the other asserted patent lacked the remote, cloud-based system, the Court found that it lacked an inventive concept.

Therefore, the Court denied the motion to dismiss as to Count I (infringement of the '050 patent) and allowed the motion to dismiss with respect to Count II (infringement of the '436 patent).

Motion to Dismiss Count III (Breach of Contract)

Regarding Count III for breach of the two non-disclosure agreements, Toast argued that Gratuity had failed to allege the elements of a breach of contract claim. The Court disagreed.

Massachusetts law requires (1) the existence of a valid and binding contract, (2) breach of the contract's terms, and (3) damages as a result of that breach.

First, the Court held that Gratuity plausibly alleged the existence of two valid and binding contracts, over Toast's objections that they had not signed each NDA. The Court noted that "[a] written contract, signed by only one party, may be binding and enforceable even without the other party's signature if the other party manifests acceptance" and that "Gratuity's continuation in conversations with Toast in light of the [second] NDA was evidence of its willingness to be bound."

Second, the Court held that Gratuity plausibly alleged breach of the contract's terms by

- describing "the specific contractual promise [Toast] failed to keep";

- alleging that Toast breached the terms of the NDAs by causing the disclosure of Gratuity's propriety information; and

- alleging that Toast improperly used "the proprietary information disclosed to it by [Gratuity] to [Gratuity's] detriment."

Third, the Court held that Gratuity alleged that it was harmed by Toast's alleged breach and did not need to plead damages in detail.

Thus, the Court denied the Motion to Dismiss as to Count III.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.