Now, nearly 20 years after Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the congressional mandate to promulgate and enforce rules for corporate attorneys has gone largely unfulfilled. But all that may change. A recent speech by SEC Commissioner Allison Herren Lee brought corporate-attorney regulation back into the spotlight. Still, regulating attorneys and, in particular, the attorney-client relationship, raises difficult questions of policy and regulatory incentives. This post dives into the rule addressing reporting responsibilities of corporate lawyers — the "Up-the-Ladder Rule" — and revisits the 2002 debate surrounding the Rule's adoption. With that background, we look to Commissioner Lee's speech and recent proposals to understand where regulation in this space may be headed and where the sticking points likely still lie.

Inward, Upward and Outward: The "Up-the-Ladder Rule" Explained

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act was passed in the wake of several corporate accounting scandals that occurred in the early 2000s.1 The Act established rules for public companies regarding disclosure, governance, auditing, reporting and risk management. Among those rules, Congress mandated the SEC, under Section 307, to "adopt minimum standards of professional conduct for attorneys appearing and practicing before the Commission in the representation of issuers."2

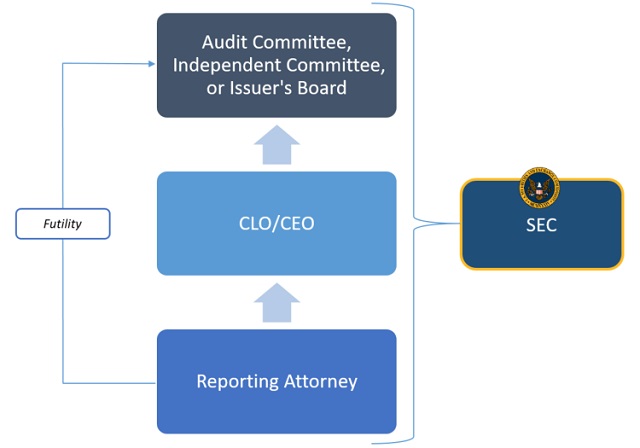

In response to that mandate, the SEC passed the so-called "Up-the-Ladder Rule," which requires an attorney to immediately report to the company's chief legal counsel (CLO) or chief executive officer (CEO) evidence that a material violation of securities laws, a breach of fiduciary duty — or a similar violation by the company or any agent thereof — has occurred, is occurring or is about to occur.3 If the attorney believes reporting to the company's CEO and/or CLO would be futile, the attorney may report to the company's audit committee, independent committee or board.4 If, within a reasonable time, the reporting attorney does not reasonably believe that the CLO or CEO has provided an appropriate response, the attorney must report the evidence of a material violation to the company's audit committee, independent committee or board, depending on the internal structure of the issuer.5 If, within a reasonable time, the reporting attorney still does not reasonably believe the issuer has made an appropriate response, the attorney must explain the reasons for this belief to the CLO, CEO and the directors to whom the attorney reported earlier.6

Throughout this process, the reporting attorney may disclose to the SEC confidential information related to her representation of the company, without the company's consent, to the extent necessary to 1) prevent the company from committing violations likely to cause substantial injury to the company or its investors; 2) prevent perjury or a fraud on the SEC; or 3) rectify the consequences of a material violation that caused substantial injury to the company or its investors.7 Although the Rule allows for this outward disclosure to the SEC throughout, it is still structured — and likely intended to function — as an inward, upward and then outward reporting mechanism.

Regulating Corporate Attorneys: The 2002 Up-the-Ladder Debate

Unsurprisingly, the Up-the-Ladder Rule was controversial when proposed in 2002 because it created tension between the protections afforded corporate clients by the attorney-client privilege and Congress' desire to impose reporting requirements on corporate gatekeepers to avoid significant financial scandals. However, regulating lawyers' relationships with their corporate clients raises thornier questions than regulating other areas of corporate governance and reporting. Section 10A of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934,8 for example, requires financial auditors to report to the SEC when they discover a likelihood of illegal activity during a financial audit. But outside auditors are generally regarded as "public watchdogs,"9 and communications with auditors are not — perhaps for that reason — entitled to any direct, affirmative privilege in their relationship with corporate clients.10 As evidenced by the 2002 debate surrounding the Up-the-Ladder Rule and Congress' Section 307 mandate, however, regulating the attorney-client relationship prompts more questions and debate.

In public comments submitted in 2002, those in favor of the Up-the-Ladder Rule emphasized that a corporate lawyer's duty is to the corporation. They argued that any illegality by the managers or directors is not authorized by the corporation, and therefore the officers or directors do not have any authority to assert the organization's confidentiality rights. Proponents further argued that corporate agents already have powerful incentives to seek legal advice, and that the communications most likely to be deterred by additional rules do not have social value or legitimacy.11

Those against the regulation emphasized the sanctity of the attorney-client relationship and the underlying importance of client candor. They countered that external reporting requirements would actually lead to an increase in corporate malfeasance because corporate clients would resist seeking informed legal advice.12 Reporting requirements, they argued, pit the attorney's self-protection against the client's best interests and, as a result, lead to less robust and nuanced legal analysis.13

Commissioner Lee's Speech: A Harbinger for Change?

Perhaps because of the difficulty in regulating in this space, the Up-the-Ladder Rule remains the SEC's only adopted rule under the Sarbanes-Oxley Section 307 mandate. What's more, the Up-the-Ladder Rule has not been enforced by the SEC — at least in terms of official enforcement actions by the SEC's Division of Enforcement — in the nearly 20 years since it was passed.14

All that may change, however. In her recent speech, Commissioner Lee expressed discontent with the singularity of the Up-the-Ladder Rule and its lack of enforcement. She lamented the current lack of standards for assessing corporate lawyers' "bad advice" and the harm that can result to "the investing public and capital markets more broadly." She also denounced the "race to the bottom" and "goal-directed reasoning" that can occur "when specialized professionals like securities lawyers compete for clients in high stakes matters and are pressured to provide the answers their clients seek."

Commissioner Lee's speech seems to signal both a renewed vigor in enforcing the Up-the-Ladder Rule and a desire to promulgate additional rules under Congress' Section 307 mandate more broadly. "The time is ripe to return to this unfinished business," Lee said. In addition to an increased focus on the Up-the-Ladder Rule, she also offered the following proposals:

- provide greater detail on a lawyer's obligation to a corporate client, including, in particular, how the lawyer's advice must reflect the interests of the corporation and its shareholders, rather than the executives who hired the lawyer

- promulgate minimum standards to ensure an "independent and rigorous analysis" of materiality issues

- promulgate minimum standards regarding attorney competence and expertise

- impose continuing education requirements that apply to securities lawyers advising public companies

- require some degree of oversight at the law firm level, akin to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) oversight of public accounting firms that prepare audit reports for public companies

Additional Considerations

Whether — and how — the SEC takes up Commissioner Lee's proposals remains an open question. But contemplated additional enforcement and rulemaking in this area would likely raise similar questions to those raised two decades ago. Expect the ensuing debate to highlight how some of Commissioner Lee's proposals are more controversial than others. For example, continuing lawyer education requirements will likely face less opposition than materiality-analysis requirements or heightened Up-the-Ladder enforcement. Either way, the Commission seems to have its eyes on this space, and you can expect additional developments to come.

Footnotes

1 15 U.S.C. §§ 7201 et seq.

2 Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 § 307, 15 U.S.C. § 7245.

3 See 17 C.F.R. §§ 205.2(i), 205.3(b)(1).

4 17 C.F.R. § 205.3(b)(4) provides that if the reporting attorney reasonably believes that it would be futile to report to the CLO and the CEO, the attorney may go directly to the issuer's audit committee. If the issuer lacks an audit committee, then the attorney may go to the issuer's independent committee. If the issuer lacks an independent committee, the attorney may go to the issuer's board.

5 17 C.F.R. § 205(b)(3). Like the structure of 17 C.F.R. § 205.3(b)(4), the attorney must go directly to the issuer's audit committee or, if the issuer lacks an audit committee, the issuer's independent committee or, if the issuer lacks an independent committee, the issuer's board.

6 17 C.F.R. § 205(b)(9).

7 17 C.F.R. § 205.3(d)(2).

8 15 U.S.C. § 78j-1.

9 See United States v. Arthur Young & Co., 465 U.S. 805, 817–18 (1984) ("[The] 'public watchdog' function demands that the accountant maintain total independence from the client at all times ... .").

10 Note that disclosure to an outside auditor generally does not waive any work-product privilege unless the disclosure was made "in a manner which substantially increases the opportunity for potential adversaries to obtain the information." E.g., Breuder v. Bd. of Trustees of Cmty. Coll. Dist. No. 502, No. 15 CV 9323, 2021 WL 4283464, at *9 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 21, 2021). But a lack of waiver is different from an affirmative privilege, as are the incentives created under each.

11 See, e.g., William H. Simon, Saunders Professor of Law at Stanford University, Comment on Proposed Rules on Standards of Attorney Conduct Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (Dec. 13, 2002).

12 See, e.g., Elliot G. Sagor, New York Council of Defense Lawyers, Comment on Proposed Rules on Standards of Attorney Conduct Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (Dec. 18, 2002).

13 See, e.g., Alfred P. Carlton Jr., President, American Bar Association, Comment on Proposed Rules on Standards of Attorney Conduct Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (April 2, 2003).

14 One U.S. District Court opinion addresses 17 C.F.R. § 205.3 in the context of an SEC enforcement action, but the agency did not allege direct violations of the statute. SEC v. Spiegel, Inc., No. Civ.A. 03 C 1685, 2003 WL 22176223, at *44–45 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 15, 2003). Some private litigation matters have considered 17 C.F.R. § 205 in certain contexts, see, e.g., Wadler v. Bio–Rad Laboratories, Inc, 212 F.Supp.3d 829, 857 (N.D. Cal. 2016) (considering Section 307 in comparison to California attorney ethics rules), but these circumstances are limited as Section 307 does not provide for a private right of action against attorneys, see 17 C.F.R. § 205.7.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.