1 Legal framework

1.1 Which legislative and regulatory provisions govern the banking sector in your jurisdiction?

The Bank Act, which is a federal statute enacted by the Parliament of Canada, is the primary statute that governs the banking sector in Canada. The Bank Act regulates:

- domestic banks ( Schedule I);

- foreign subsidiary banks that are controlled by eligible foreign institutions ( Schedule II); and

- bank branches of foreign institutions ( Schedule III).

It has been supplemented by numerous regulations made under its authority, which elaborate on the rules and principles it contains.

Provincial legislation generally does not apply to the banking activities of banks, as federally regulated financial institutions. However, provincial provisions may apply to banking activities as long as they do not "in any way impair any activities that are 'vital or essential to banking' such that Parliament might be forced to specifically legislate to override the provincial law" ( Bank of Montreal v Marcotte, [2014] 2 SCR 725, at para 66).

1.2 Which bilateral and multilateral instruments on banking have effect in your jurisdiction? How is regulatory cooperation and consolidated supervision assured?

Global regulatory bodies have regulatory impact on Canadian financial institutions. Both the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and the Bank of Canada participate in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) as part of their role as members of the Bank for International Settlements. While the BCBS does not issue binding regulation, it has influence internationally through its role in standard setting for prudential regulation of banks, including capital adequacy and liquidity requirements. The BCBS's recommendations are generally implemented in Canada by OSFI and the Bank of Canada.

In addition, prudential regulators such as OSFI publish guidelines and advisories for the purpose of ensuring compliance with requirements under federal financial institution legislation. The guidelines and advisories fall into four general categories:

- capital adequacy requirements (ie, Tier 1 and 2 capital and liquidity and leverage ratios);

- limits and restrictions on lending;

- accounting and disclosure; and

- sound business and financial practices.

1.3 Which bodies are responsible for enforcing the applicable laws and regulations? What powers (including sanctions) do they have?

OSFI and the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC) are the primary regulatory bodies for banks. OSFI is responsible for prudential regulation and conducts regular reviews of banks regarding compliance with the guidelines it establishes for capital, reporting and business practices. FCAC is responsible for consumer protection and oversees banks' compliance with certain voluntary codes of conduct.

Both OSFI and FCAC have the power to impose administrative monetary penalties for violations of their enabling legislation - that is, the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada Act and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Act, respectively. OSFI can also enforce penal sanctions under the Bank Act: the sanctions for contraventions include fines of up to C$5 million (C$1 million for a natural person) and imprisonment for up to five years. The sanctions will vary depending on the severity of the infraction and the size of the bank.

In addition to imposing monetary sanctions, the two regulators often require banks to improve their internal controls and governance, and have even required that directors and officers be replaced if they were involved in the wrongdoing or failed in their supervisory duties.

Several other regulatory bodies are also involved in enforcing the laws and regulations that apply to banks in Canada. The Department of Finance (Canada) is the government body responsible for banks; it proposes changes to the legislation and adopts new regulations that govern banks. Banks are also reporting entities under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, subject to reporting and compliance obligations relating to anti-money laundering and terrorist financing . These requirements are enforced by the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada.

1.4 What are the current priorities of regulators and how does the regulator engage with the banking sector?

The current priorities of the OSFI and FCAC are to monitor and address the evolving economic situation with COVID-19. As a result, both regulators are taking a number of steps to reprioritise their work and requirements to allow banks to focus on their resilience efforts.

OSFI is engaging with the banking sector by maintaining frequent contact with banks to assess their operational capacity and actions to address the current environment. It is also publishing various notices to the sector on its website.

These notices indicate the changes that OSFI is implementing to its regulatory requirements during this time as it reprioritises. For example, OSFI has suspended all of its consultations and policy development on new or revised guidance until conditions stabilise. Further, OSFI has adjusted a number of regulatory reporting requirements, and has encouraged banks to use their capital and liquidity buffers as appropriate. OSFI has also prioritised supporting the efforts of the BCBS to provide additional operational capacity for banks and supervisors to respond to the immediate financial stability priorities, outlining how these will be implemented domestically to ensure they are fit for purpose in the Canadian context.

Similarly, FCAC is engaging with the banking sector by publishing and updating an online notice adjusting its regulatory expectations in the current environment. FCAC has committed to working closely with banks to minimise the impact of regulatory requirements on their efforts to deliver essential services to Canadians.

2 Form and structure

2.1 What types of banks are typically found in your jurisdiction?

There are three types of banks in Canada:

- Schedule I banks: domestic banks, authorised under the Bank Act to accept deposits, which may be eligible for deposit insurance provided by the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation;

- Schedule II banks: foreign bank subsidiaries, authorised under the Bank Act to accept deposits, which may be eligible for deposit insurance provided by the Canada Deposit and Insurance Corporation. Foreign bank subsidiaries are controlled by eligible foreign institutions; and

- Schedule III banks: foreign banks that have been authorised under the Bank Act to operate branches in Canada. The activities of a branch may be restricted to lending or may be 'full service', which includes the offer of retail deposit accounts.

2.2 How are these banks typically structured?

Schedule I and Schedule II banks are structured as corporations.

Any acquisitions of significant interest - that is, of a level that is greater than 10% of a class of shares - in a bank must be approved by the minister of finance.

2.3 Are there any restrictions on foreign ownership of banks?

Foreign ownership is generally permitted under the Bank Act. However, it will be taken into account by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) in applications to acquire a significant interest or more in a bank.

If the applicant is a national of a country that is not a member of the World Trade Organization, prior to granting approval for the applicant to acquire more than 10% of the shares of a bank, the minister of finance must be satisfied that reciprocal treatment would be available for Canadians under the laws of that jurisdiction. Additionally, no foreign government, political subdivision of a foreign country or agent of a foreign government or entity controlled by a foreign government may be issued shares of a bank.

2.4 Can banks with a foreign headquarters operate in your jurisdiction on the basis of their foreign licence?

Banks with a foreign headquarters must obtain authorisation under the Bank Act to have a financial establishment in Canada . This includes establishing a Canadian subsidiary or a bank branch, as well as other permitted entities in Canada.

A foreign bank may also apply to OSFI to register a representative office in Canada and - with the approval of the governor in council and subject to any terms and conditions that are attached to the approval - locate its head office in Canada and, from that office, issue directions and do all other things reasonably necessary for the conduct of its banking business outside Canada.

3 Authorisation

3.1 What licences are required to provide banking services in your jurisdiction? What activities do they cover?

No bank or bank branch can carry on the business of banking in Canada without first obtaining the approval of the minister of finance and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI). In order for a bank to be authorised under the Bank Act, it requires both:

- the issuance of letters patent by the minister of finance; and

- the making of an order by OSFI.

The Bank Act provides that a bank can carry on only those activities that are considered to be the 'business of banking' and business generally related to banking. These activities include:

- taking deposits and making loans;

- providing any financial service;

- acting as a financial agent;

- providing investment counselling services and portfolio management services;

- issuing payment, credit or charge cards; and

- operating a payment, credit or charge card plan in cooperation with others (including other financial institutions).

3.2 What requirements must be satisfied to obtain a licence?

OSFI assesses applications for the incorporation of banks and makes recommendations to the minister of finance, who makes the ultimate determination. To do so, the minister of finance takes into account a number of factors, including:

- the nature and sufficiency of the financial resources of the applicant(s) as a source of continuing financial support for the bank;

- the soundness and feasibility of the plans of the applicant(s) for the future conduct and development of the business of the bank;

- the business record and experience of the applicant(s);

- the character and integrity of the applicant(s) or, if any applicant is a body corporate, its reputation for being operated in a manner that is consistent with the standards of good character and integrity;

- whether the bank will be operated responsibly by persons with the competence and experience suitable for involvement in the operation of a financial institution;

- the impact of any integration of the businesses and operations of the applicant(s) with those of the bank on the conduct of those businesses and operations;

- the extent to which the proposed corporate structure of the applicant or applicants and their affiliates may affect the supervision and regulation of the bank, having regard to the nature and:

-

- the proposed financial services activities to be carried out by the bank and its affiliates; and

- the degree of supervision and regulation applying to the proposed financial services activities to be carried out by the affiliates of the bank; and

- the best interests of the financial system in Canada.

3.3 What is the procedure for obtaining a licence? How long does this typically take?

The application process is outlined in OSFI's Guide for Incorporating Banks and Federally Regulated Trust and Loan Companies and is comprised of three phases:

- pre-application;

- letters patent; and

- order.

Pre-application (Phase 1):

- The applicant meets with OSFI to discuss the proposed application.

- The applicant submits the Phase 1 information requirements outlined in OSFI's guide (above) to OSFI.

- The applicant meets with OSFI to discuss its submissions and business plan.

- OSFI issues a letter to the applicant setting out its preliminary views and expectations.

Letters patent (Phase 2):

- The applicant publishes a notice of intention to apply for letters patent.

- The applicant submits its applications for letters patent and an order to OSFI.

- OSFI may request further information and will meet with the applicant.

- OSFI submits its recommendation to the minister regarding issuing letters patent.

Order (Phase 3):

- If letters patent are issued by the minister, OSFI will continue its review of the application with respect to issuing an order.

- OSFI may make additional requests for information and will have further meetings with the applicant.

- OSFI will carry out its onsite review.

- If any material issues or concerns identified have been adequately addressed, OSFI will issue the order.

The timeline for the assessment of each application depends on the specific facts and circumstances. However, for a newly incorporated bank, the Bank Act specifies that OSFI will not make an order more than one year after the issuance of letters patent incorporating the bank. The timing relating to the making of an order largely depends on the on-site review readiness of the bank.

4 Regulatory capital and liquidity

4.1 How are banks typically funded in your jurisdiction?

Canadian banks fund their activities through a variety of sources. They can borrow from the Bank of Canada for short-term borrowing, daylight loans and liquidity requirements. Large banks may also have stable deposit bases and issue term deposits, bank deposit notes and bankers' acceptances.

For foreign banks, funding depends on whether they have a full-service branch or a lending branch in Canada. Foreign bank full-service branches cannot accept retail deposits, but can otherwise access the Canadian markets to fund their activities. Lending branches cannot take any deposits in Canada and have no access to funding via the Canadian markets. They must get funding from outside of Canada or borrow money from other financial institutions.

4.2 What minimum capital requirements apply to banks in your jurisdiction?

Banks must maintain adequate capital and adequate and appropriate forms of liquidity pursuant to Section 485(1) of the Bank Act. This is measured by compliance with the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions' (OSFI) Capital Adequacy Requirements Guideline.

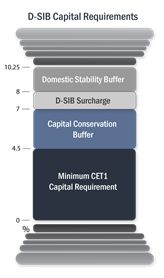

Banks must maintain a level of capital at least equal to Tier 1 capital (subject to adjustments). However, minimum capital requirements are greater for certain large financial institutions in Canada. OSFI designates banks that are domestic systemically important banks (D‑SIBs), which are of domestic systemic importance based on OSFI's assessment of a range of indicators such as:

- asset size;

- intra-financial claims and liabilities; and

- the banks' roles in domestic financial markets and in financial infrastructures.

D‑SIBs will be subject to a common equity Tier 1 capital (CET1) surcharge equal to 1% of risk‑weighted assets (RWA). The 1% capital surcharge is periodically reviewed in light of national and international developments. This is consistent with the levels and timing set out in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) D‑SIB framework.

Finally, OSFI has adopted the BCBS framework for the assessment of global systemically important banks (GSIBs). The assessment methodology for GSIBs follows an indicator-based approach agreed by the BCBS that will determine which banks are to be designated as GSIBs and subject to additional loss absorbency requirements that range from 1% to 2.5% CET1, depending on a bank's global systemic importance. For Canadian banks that are designated a GSIB, the higher of the D‑SIB and GSIB surcharges will apply in determining the buffer.

4.3 What legal reserve requirements apply to banks in your jurisdiction?

Banks must maintain a capital conservation buffer, which establishes a safeguard above the minimum capital requirements and can only be met with CET1.

D‑SIBs are subject to an additional capital buffer to protect against risks in the financial system. Referred to as the 'domestic stability buffer', it has been set at 1% of total risk-weighted assets, effective 13 March 2020. It is not a Pillar 1 buffer and breaches will not result in banks being subject to automatic constraints on capital distributions. If a D-SIB breaches the buffer (ie, dips into the buffer when it has not been released), OSFI will require a remediation plan.

5 Supervision of banking groups

5.1 What requirements apply with regard to the supervision of banking groups in your jurisdiction?

Under the Bank Act, directors have a general duty to manage or supervise the management of the business and affairs of the bank. Directors also have specific duties to establish an audit committee and a conduct review committee, and to maintain policies for, among other things, disclosure to customers, resolving conflicts of interest, and dealing with complaints (see Section 157 of the Bank Act).

Members of the board of directors of a bank can be held personally responsible for infractions under the Bank Act, which provides that offences may be imputed to officers and directors who participate in the offence or assent to or encourage the commission of the offence. Directors can also be held personally liable where they fail to act in good faith and knowingly turn a blind eye to an offence or allow it to continue to be committed.

Additionally, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) requires disclosure from all federally regulated banks on a monthly, quarterly and annual basis, and examines each bank on an annual basis to determine its compliance with the Bank Act and to assess its financial condition.

5.2 How are systemically important banks supervised in your jurisdiction?

As of March 2020, the Bank of Montreal, Bank of Nova Scotia, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, National Bank of Canada, Royal Bank of Canada, and Toronto-Dominion Bank are currently designated as domestic systemically important banks (D‑SIBs).

D-SIBs are subject to enhanced supervision by OSFI, including more frequent reviews and regular stress testing for capital and liquidity, and D-SIBs are subject to a CET1 surcharge equal to 1% of risk-weighted assets (RWA). The 1% capital surcharge will be periodically reviewed in light of national and international developments. This is consistent with the levels and timing set out in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision D-SIB framework. In addition, D-SIBs are subject to an additional capital buffer to protect against risks in the financial system. The buffer, referred to as the 'domestic stability buffer', was initially established at a rate of 2.25% of total RWA.

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (Canada)

Recently, due to COVID-19, it has been reduced from 2.25% to 1% of total RWA.

5.3 What is the role of the central bank?

Established under the Bank of Canada Act, the Bank of Canada:

- regulates credit and currency matters;

- oversees clearing and settlement systems; and

- creates Canada's monetary policy.

In addition, it consults, on an informal and confidential basis, with senior officers of banks. In its role as lender of last resort, the Bank of Canada also has the authority to provide liquidity to banks and markets to stabilise the financial sector.

6 Activities

6.1 What specific regulations apply to the following banking activities in your jurisdiction: (a) Mortgage lending? (b) Consumer credit? (c) Investment services? and (d) Payment services and e-money?

(a) Mortgage lending?

Federal statutes - including the Bank Act, SC 1991, c 46 (Bank Act) and its regulations, and the Trust and Loan Companies Act, SC 1991, c 45 (Trust and Loan Companies Act) and its regulations - set out a number of consumer protection provisions applicable to federally regulated mortgage lenders. The applicable provisions set out requirements relating to issues such as:

- credit business practices;

- disclosure requirements regarding charges;

- the cost of borrowing;

- prepayment and interest;

- notice requirements;

- complaints; and

- the establishment of consumer-focused procedures.

The Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC) has oversight of federal consumer protection legislation applicable to federally regulated financial institutions, including provisions of the Bank Act, the Trust and Loan Companies Act and their regulations.

Furthermore, mortgage lending by provincially regulated entities is governed by consumer protection legislation and/or mortgage brokerage legislation, depending on the jurisdiction (ie, credit unions and private lenders), as follows:

- British Columbia: the Mortgage Brokers Act, RSBC 1996, c 313;

- Alberta: the Real Estate Act, RSA 2000, c R-5;

- Saskatchewan: the Mortgage Brokerages and Mortgage Administrators Act, SS 2007, c M-20.1; the Trust and Loan Corporations Act, 1997, SS 1997, c T-22.2;

- Manitoba: the Mortgage Brokers Act, CCSM c M210;

- Ontario: the Mortgage Brokerages, Lenders and Administrators Act, 2006, SO 2006, c 29; Quebec: the Civil Code of Quebec, CQLR c CCQ-1991;

- Newfoundland and Labrador: the Mortgage Brokers Act, RSNL 1990, c M-18;

- Nova Scotia: the Mortgage Brokers and Lenders Registration Act, RSNS 1989, c 291;

- New Brunswick: the Mortgage Brokers Act, RSNB 2014, c 41; Cost of Credit Disclosure and Payday Loans Act, SNB 2002, c C-28.3;

- Prince Edward Island: the Business Practices Act, RSPEI 1988, c B-7; the Consumer Protection Act, RSPEI 1988, c C-19; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSPEI 1988, c U-2;

- Yukon: the Consumers Protection Act, RSY 2002, c 40;

- Northwest Territories: the Consumer Protection Act, RSNWT 1988, c C-17; the Cost of Credit Disclosure Act, SNWT 2010, c 23; and

- Nunavut: the Consumer Protection Act, RSNWT (Nu) 1988, c C-17.

The licensing and registration requirements vary by province with respect to the lending, brokering and administration of mortgages on property in that province. There are nuances for each province and territory on the procedures for registering mortgages on title to property and the priority of such registered mortgages.

There is debate as to the extent of application of the federal Interest Act, RSC, 1985, c I-15 to today's mortgage industry in Canada.

(b) Consumer credit?

The Bank Act and its regulations and the Trust and Loan Companies Act and its regulations set out a number of consumer protection provisions applicable to federally regulated financial institutions. The legislation sets out requirements relating to issues such as:

- credit business practices;

- disclosure requirements regarding charges;

- the cost of borrowing and interest;

- notice requirements;

- complaints; and

- the establishment of consumer-focused procedures.

FCAC has oversight of federal consumer protection legislation applicable to federally regulated financial institutions, including provisions of the Bank Act, the Trust and Loan Companies Act and their regulations. Similarly, most provinces and territories have a provincial body that oversees compliance of consumer protection matters, as discussed below.

Consumer credit is also regulated by provincial and territorial consumer protection legislation and their regulations, as follows:

- British Columbia: the Business Practices and Consumer Protection Act, SBC 2004, c 2;

- Alberta: the Consumer Protection Act, RSA 2000 c C-26.3; the Unconscionable Transactions Act, RSA 2000, c U-2; SK: the Consumer Protection and Business Practices Act, SS 2013, c C-30.2; the Cost of Credit Disclosure Act, RSS 1978, c C-41; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSS 1978, c U-1;

- Manitoba: the Business Practices Act, CCSM c B120; the Consumer Protection Act, CCSM C 200; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, CCSM c U20;

- Ontario: the Consumer Protection Act, 2002, SO 2002, c 30, Sch A; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSO 1990, c U2;

- Quebec: the Consumer Protection Act, CQLR c P-40.1;

- Newfoundland and Labrador: the Consumer Protection and Business Practices Act, SNL 2009, c C-31.1;

- Nova Scotia: the Consumer Protection Act, RSNS 1989, c 92; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSNS 1989, c 481; the Consumer Creditors' Conduct Act, RSNS 1989, c 91;

- New Brunswick: the Cost of Credit Disclosure and Payday Loans Act, SNB 2002, c C-28.3; the Provincial Offences Procedure Act, SNB 1987, c P-22.1; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSNB 2011, c 233;

- Prince Edward Island: the Business Practices Act, RSPEI 1988, c B-7; the Consumer Protection Act, RSPEI 1988, c C-19; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSPEI 1988, c U-2;

- Yukon: the Consumers Protection Act, RSY 2002, c 40;

- Northwest Territories: the Consumer Protection Act, RSNWT 1988, c C-17; the Cost of Credit Disclosure Act, SNWT 2010, c 23; and

- Nunavut: Consumer Protection Act, RSNWT (Nu) 1988, c C-17.

This consumer protection legislation must be considered regardless as to whether the lender is provincially or federally chartered (for more information on the interaction between federal and provincial consumer credit legislation, see question 10.1 below). Generally, provincial and territorial Consumer Protection Acts:

- provide statutory rights to consumer borrowers;

- set out specific requirements regarding the content (ie, default terms) and performance of consumer credit contracts; and

- provide detailed obligations regarding proper disclosure of the cost of consumer credit.

There are a number of notable differences between provinces with regard to the requirements of consumer protection legislation as it applies to consumer credit lenders. For example, certain provinces (ie, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island) require lenders governed by provincial legislation to obtain 'lending' licences. Furthermore, the legislation in Alberta, British Columba and Saskatchewan includes additional requirements and restrictions for 'high-cost credit', and sets the maximum amount of 'interest' that can be charged to consumers in those provinces.

In addition, all loans in Canada are governed by the cost of credit provisions contained under the Criminal Code, RSC, 1985, c C-46, and are subject to the provisions of the Interest Act, RSC, 1985, c I-15.

Finally, provincial legislation contains additional, specific statutory requirements for certain consumer credit products, such as pay-day loans and motor vehicle loans. These provisions either are found under free-standing legislation or form part of various consumer protection statutes.

Although provincial laws dealing with consumer credit are substantially similar across provinces and territories, the specific language of each applicable act should be consulted for the particular requirements in each province.

(c) Investment services?

Many different types of investment vehicles are offered and available in Canada, including annuities, treasury bills, guaranteed income certificates, exchange-traded funds, mutual funds, segregated funds, securities and stocks.

Financial institutions such as banks, credit unions, caisses populaires and trust companies can offer registered and unregistered accounts, and other deposit or saving-type products for investment purposes.

Federally regulated financial institutions are governed by federal legislation such as the Bank Act and its regulations, and the Trust and Loan Companies Act and its regulations. Provincially regulated entities, such as credit unions, are governed by provincial legislation applicable in their incorporating jurisdiction. All registered accounts must comply with the federal Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c 1 (5th Supp).

Investments in other investment vehicles - such as stocks, bonds or gold - can be made through brokers or with brokerage firms. These entities are regulated by the following provincial securities laws:

- British Columbia: the Securities Act, RSBC 1996, c 418;

- Alberta: the Securities Act, RSA 2000, c S-4;

- Saskatchewan: the Securities Act, 1988, SS 1988-89, c S-42.2;

- Manitoba: the Securities Act, RSM 1988, c S50, CCSM, c S50;

- Ontario: the Securities Act, RSO 1990, c S.5;

- Quebec: the Securities Act, CQLR, c V-1.1;

- Newfoundland and Labrador: the Securities Act, RSN 1990, c S-13;

- Nova Scotia: the Securities Act, RSNS 1989, c 418;

- New Brunswick: the Securities Act, SNB 2004, c S-5.5;

- Prince Edward Island: the Securities Act, SPEI 2007, c 17;

- Yukon: the Securities Act, SY 2007, c 16;

- Northwest Territories: the Securities Act, SNWT 2008, c 10; and

- Nunavut: the Securities Act, SNu 2008, c 12

The provincial securities regulatory authorities, which administer the securities laws applicable in their province are as follows:

- British Columbia: the British Columbia Securities Commission;

- Alberta: the Alberta Securities Commission;

- Saskatchewan: the Financial and Consumer Affairs, Saskatchewan;

- Manitoba: the Manitoba Securities Commission;

- Ontario: the Ontario Securities Commission;

- Quebec: the Autorité des marchés financiers du Québec;

- Newfoundland and Labrador: the Securities Commission of Newfoundland and Labrador;

- Nova Scotia: the Nova Scotia Securities Commission;

- New Brunswick: the Financial and Consumer Services Commission of New Brunswick;

- Prince Edward Island: the Office of the Superintendent of Securities of Prince Edward Island;

- Yukon: the Office of the Yukon Superintendent of Securities;

- Northwest Territories: the Office of the Superintendent of Securities Government of Northwest Territories; and

- Nunavut: the Office of the Superintendent of Securities for Nunavut.

These entities make up the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA). The CSA's objective is to improve, coordinate and harmonise the regulation of Canadian capital markets. The CSA enacts national instruments and national policies, and is responsible for developing the 'passport' system.

Furthermore, self-regulatory organizations such as the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada and the Mutual Funds Dealers Association of Canada, as well as the stock exchanges in Canada, also serve a regulatory function. Banks often team up with provincial brokerages (which operate nationally) in order to offer a wider selection of products to clients under the bank umbrella.

(d) Payment services and e-money?

Payments Canada (formerly the Canadian Payments Association) was created under the Canadian Payments Act, RSC, 1985, c C-21 to:

- establish and operate national systems for the clearing and settlement of payments among member financial institutions;

- facilitate the interaction of its clearing and settlement systems with other systems;

- and facilitate the development of new payment technologies.

Membership of Payments Canada is mandatory for most financial institutions.

Payments Canada owns and is responsible for operating the two national payment systems in Canada:

- the Automated Clearing Settlement System (ACSS); and

- the Large Value Transfer System (LVTS).

Payments Canada sets bylaws and rules and has created payment system procedures for both the ACSS and LVTS. These rules and procedures govern the daily operations of participants in the national clearing and settlement system. Under the Canadian Payments Act, the minister of finance has authority to review or amend such payment rules, and issue directives to make, amend or repeal bylaws, rules or standards.

Payment Canada's LVTS and ACSS are overseen by the Bank of Canada by virtue of the Payment Clearing and Settlement Act, SC 1996, c 6, Sch. The act assigns the Bank of Canada with responsibility for overseeing automated clearing and settlement systems for the purpose of controlling systemic risk or payments systemic risk.

In addition, the Bills of Exchange Act provides the statutory framework governing cheques, promissory notes and other bills of exchange.

Finally, the Bank Act and other federal financial institution statutes contain a number of payments-related provisions.

7 Reporting, organisational requirements, governance and risk management

7.1 What key reporting and disclosure requirements apply to banks in your jurisdiction?

Banks must file regular corporate returns and financial returns throughout the year . A listing of financial returns is found on the website of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) (www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/Eng/fi-if/rtn-rlv/fr-rf/Pages/dti_req.aspx).

Certain financial information filed by banks is publicly accessible on OSFI's website.

7.2 What key organisational and governance requirements apply to banks in your jurisdiction?

Corporate governance is a set of relationships between a bank's management, its board of directors, its shareholders and other stakeholders. It also provides the structure through which the objectives of the bank are set, and through which the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined.

According to OSFI, the quality of bank corporate governance practices is an important factor in maintaining the confidence of depositors.

The role of the board is to approve decisions and provide oversight relating to:

- strategy, including major strategic decisions such as M&A activity, risk management and internal controls;

- appointment, performance review and compensation of senior officers;

- succession planning; and

- internal and external audits of the bank.

The board is not responsible for the ongoing and detailed operationalisation of its decisions; this is the responsibility of senior officers of the bank. On the other hand, the board is expected to provide challenge, advice and guidance to the senior officers, as appropriate . Overall, the board should be satisfied that the decisions and actions of senior officers are consistent with the board-approved business plan, strategy and risk appetite of the bank, and that the corresponding internal controls are sound.

A bank that is part of a larger corporate group (another bank or company in Canada, or another company abroad) may be subject to or may adopt certain policies of the parent. In this situation, the subsidiary board should be satisfied that these policies are appropriate for the Canadian bank's business plan, strategy and risk appetite, and comply with specific Canadian regulatory requirements.

According to OSFI, the hallmarks of an effective board include demonstrated sound judgement, initiative, proactivity, responsiveness and operational excellence. Board members should strive to facilitate open communication, collaboration and appropriate debate in the decision-making process.

OSFI expects boards to demonstrate relevant financial industry and risk management expertise; and collectively, they should be independent from management and the operations of the bank . OSFI recommends that role of the board chair should be separate from the CEO, as this is critical in maintaining the board's independence and its ability to execute its mandate effectively.

Finally, OSFI promotes diversity on boards, which is a factor included in the checklist of assessment criteria (see www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/Eng/Docs/09-Board_of_Directors.pdf).

7.3 What key risk management requirements apply to banks in your jurisdiction?

OSFI's Corporate Governance Guideline requires banks to develop an enterprise-wide, board-approved risk appetite framework that outlines the risk-taking activities of the bank and the benchmarks and limits for the amount of risk that the bank is willing to accept. It is intended to be forward looking and should consider the material risks to the bank, in addition to its reputation. The policies, practices and procedures of the bank should all support the risk appetite framework.

Depending on the nature and size of the bank, OSFI advises the board of directors to establish a board risk committee to oversee risk management on an enterprise-wide basis. All committee members, including the chair, should be non-executives of the bank, to ensure that risk management activities are independent from operational management of the bank. The board risk committee receives reports on significant risks of the bank and its exposures relative to its risk appetite. It provides input on how material exceptions or breaches to risk policies and controls are identified, measured, monitored, controlled and addressed.

OSFI also advises that a bank should also have a senior officer (the chief risk officer) who is responsible for overseeing all risks on an enterprise-wide and disaggregated level. Like the board risk committee, the chief risk officer should work independently of the business lines or operational management, providing regular reports to the board of directors, the board risk committee and senior management on whether the bank is operating within the risk appetite framework.

The Corporate Governance Guideline also specifies that the chief risk officer and the board risk committee should not be directly involved in revenue generation or in the management and financial performance of any business line or product of the bank. In addition, the chief risk officer's compensation should not be linked to such performance.

7.4 What are the requirements for internal and external audit in your jurisdiction?

The Bank Act requires that each bank establish an audit committee comprised of non-employee directors, a majority of whom are not 'affiliated' with the bank. The statutory duties of the audit committee include:

- reviewing the bank's annual statements;

- evaluating and approving internal control procedures; and

- providing input on the effectiveness of the bank's internal controls and the adequacy of practices for reporting and determining financial reserves.

It also approves the bank's internal and external audit plans.

OSFI's Corporate Governance Guideline stipulates that the audit committee is responsible for overseeing the performance of the bank's internal audit function - whether or not part or all of the audit is outsourced. This responsibility includes:

- recommending to the shareholders the appointment or removal of an external auditor (as well as the scope and terms of this auditor); and

- reporting annually to the board of directors on the effectiveness of the external auditor and the overall results of the audit.

8 Senior management

8.1 What requirements apply with regard to the management structure of banks in your jurisdiction?

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions' (OSFI) Corporate Governance Guideline creates a critical distinction between the responsibilities of a bank's board of directors and the responsibilities of its senior management. While the board of directors sets the direction and general oversight of the management and operations of the entire bank, the senior management implements the board of directors' decisions and directs and oversees the operations of the bank.

Banks are expected to inform OSFI of changes to its senior officers and describe the mandates of any senior management committees it uses.

Senior officers are the chief executive officer (CEO) and individuals who are directly accountable to the CEO. These can include the heads of the bank's oversight functions, such as the chief financial officer, chief risk officer, chief compliance officer, chief internal auditor and chief actuary; as well as the heads of major business platforms or units.

8.2 How are directors and senior executives appointed and removed? What selection criteria apply in this regard?

The directors and senior executives of a bank are appointed and removed according to the bank's bylaws - typically, at annual meetings, shareholders elect and remove directors, and directors appoint and remove officers. As part of OSFI's ongoing supervisory process of banks, a bank should notify OSFI as early as possible in the process of any potential changes to the membership of the board of directors and senior management, and the process and criteria used by the bank to select its directors and executives should be transparent to OSFI.

The Bank Act requires a bank to have at least seven directors. At least one-half of the directors of a bank that is a subsidiary of a foreign bank and a majority of the directors of any other bank must, at the time of each director's election or appointment, be resident Canadians. Various persons are disqualified from being directors of a bank, due to factors such as the following:

- age;

- having the status of a bankrupt;

- not being a natural person; and

- being a governmental minister.

No more than 15% of the directors of a bank may, at each director's election or appointment, be employees of the bank or a subsidiary of the bank. However, up to four persons who are employees of the bank or a subsidiary of the bank may be directors of the bank if those directors constitute not more than one-half of the directors of the bank.

A director of a bank may be appointed to any office of the bank. The Bank Act also specifically requires the directors of a bank to appoint from their number a CEO who must be ordinarily resident in Canada.

8.3 What are the legal duties of bank directors and senior executives?

The Bank Act provides that the directors of a bank manage or supervise the management of the business and affairs of the bank. Their responsibilities include, but are not limited to:

- establishing the audit committee;

- establishing the conduct review committee;

- establishing procedures to resolve conflicts of interest, including techniques for the identification of potential conflict situations and for restricting the use of confidential information;

- designating a committee of the board of directors to monitor the procedures referred regarding conflicts of information and the use of confidential information;

- establishing procedures to provide for the disclosure of information to customers of the bank that is required to be disclosed by the Bank Act and for dealing with complaints;

- designating a committee of the board of directors to monitor the procedures referred to for the disclosure of information and satisfy themselves that they are being adhered to by the bank; and

- establishing investment and lending policies, standards and procedures.

The directors of a bank may, subject to the bank's bylaws, specify the duties of the bank's officers and delegate to them powers to manage the business and affairs of the bank.

Every director and officer of a bank, in exercising any of the powers of a director or an officer and discharging any of the duties of a director or an officer, is required by the Bank Act to:

- act honestly and in good faith with a view to the best interests of the bank; and

- exercise the care, diligence and skill that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances.

They must also comply with the Bank Act and its regulations, the bank's incorporating instrument and its bylaws. No contract, resolutions or bylaws can relieve any directors or officers of the bank from those duties, or from liability if they breach them.

8.4 How is executive compensation in the banking sector regulated in your jurisdiction?

The Bank Act provides that the directors of a bank may fix the remuneration of the directors, officers and employees of a bank or bank holding company.

Executive compensation is subject to disclosure rules under Canadian securities laws if the bank is a public issuer.

9 Change of control and transfers of banking business

9.1 How are the assets and liabilities of banks typically transferred in your jurisdiction?

The Bank Act provides a process for the transfer by a Canadian bank of all or substantially all of its assets to another Canadian financial institution or a foreign bank licensed to operate a branch in Canada, provided that the purchasing financial institution or authorised foreign bank assumes all or substantially all of the liabilities of the Canadian bank.

The purchaser and seller must enter into a written agreement, under which the consideration for the transfer of assets may be cash or fully paid securities of the purchaser, or any other consideration that is provided for in the agreement.

The agreement must first be submitted to the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) for approval. If approved, the selling bank must next submit the agreement to its shareholders to approve by special resolution (ie, not less than two-thirds of the shareholders of the bank entitled to vote). If approved by special resolution, the selling bank then has three months to submit the agreement to the minister of finance. The agreement is of no force and effect unless and until it is approved by the minister of finance.

The Bank Act sets out no rules on customer consent to transfers of a bank's assets and liabilities. These issues are, generally speaking, contractual matters between a bank and its customers.

9.2 What requirements must be met in the event of a change of control?

The minister of finance must approve any transaction that would result in a change of control of a bank. The definition of 'control' in the Bank Act includes any direct or indirect influence that, if exercised, would result in the person having 'control in fact' over the bank. The application to the minister of finance for such a transaction must be filed with OSFI and must contain various information prescribed by OSFI (see www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/Eng/fi-if/app/aag-gad/ti-io/tinda-iona/Pages/rpto23.aspx).

OSFI lists the following requirements that must be met for it to recommend that the minister of finance grant an approval:

- The applicant has sufficient resources to provide continuing financial support to the bank;

- The applicant's business record and experience are appropriate;

- The applicant is of good character and integrity and has a good reputation;

- Any concerns raised by the application relative to Canada's national security, international relations and international legal obligations have been addressed;

- The proposed changes to the bank's business plan are sound and feasible;

- The prospective new managers and directors of the bank have the necessary experience and competence to fulfil their roles;

- Any integration of the applicant's businesses and operations with those of the bank is appropriate for the bank;

- Any supervisory concerns presented by the proposed ownership structure of the bank are addressed;

- Any legislative compliance or public policy issues raised by the application are addressed; and

- The applicant's acquisition or increase of a significant interest in, and/or acquisition of control of, the bank, will be in the best interests of the financial system in Canada.

In addition, a Canadian bank cannot transfer more than 10% of the total value of its assets to any single person without the consent of OSFI - with some limited exceptions.

The Bank Act also prohibits a person from controlling either a bank or a bank holding company that has more than C$12 billion of equity.

10 Consumer protection

10.1 What requirements must banks comply with to protect consumers in your jurisdiction?

Banks in Canada must comply with both:

- the consumer protection provisions of applicable federal legislation including the Bank Act and the Trust and Loan Companies Act, as well as mandates from the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC); and

- requirements of provincial and territorial consumer protection legislation and their regulations.

Both the Bank Act and Trust and Loan Companies Act and their respective regulations provide direction to federally regulated financial institutions under the auspices of FCAC. FCAC is an independent agency of the government of Canada created under the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada Act, SC 2001, c 9. FCAC is responsible for ensuring compliance with the consumer protection provisions of federal statutes that address matters including the proper disclosure of cost of borrowing charges and complaint procedures. In October 2018 FCAC released a new Supervision Framework. The Supervision Framework provides FCAC stakeholders with a description of a general approach to typical supervision matters.

In addition, all of the provinces and territories in Canada have enacted consumer protection legislation that regulate businesses dealing with consumer credit and debt, as follows:

- British Columbia: the Business Practices and Consumer Protection Act, SBC 2004, c 2;

- Alberta: the Consumer Protection Act, RSA 2000 c C-26.3; the Unconscionable Transactions Act, RSA 2000, c U-2;

- Saskatchewan: the Consumer Protection and Business Practices Act, SS 2013, c C-30.2; the Cost of Credit Disclosure Act, RSS 1978, c C-41; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSS 1978, c U-1;

- Manitoba: the Business Practices Act, CCSM c B120; the Consumer Protection Act, CCSM C 200; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, CCSM c U20;

- Ontario; the Consumer Protection Act, 2002, SO 2002, c 30, Sch A; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSO 1990, c U2;

- Quebec: the Consumer Protection Act, CQLR c P-40.1;

- Newfoundland and Labrador: the Consumer Protection and Business Practices Act, SNL 2009, c C-31.1;

- Nova Scotia: the Consumer Protection Act, RSNS 1989, c 92; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSNS 1989, c 481; the Consumer Creditors' Conduct Act, RSNS 1989, c 91;

- New Brunswick: the Cost of Credit Disclosure and Payday Loans Act, SNB 2002, c C-28.3; the Provincial Offences Procedure Act, SNB 1987, c P-22.1; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSNB 2011, c 233;

- Prince Edward Island: the Business Practices Act, RSPEI 1988, c B-7; the Consumer Protection Act, RSPEI 1988, c C-19; the Unconscionable Transactions Relief Act, RSPEI 1988, c U-2;

- Yukon: the Consumers Protection Act, RSY 2002, c 40;

- Northwest Territories: the Consumer Protection Act, RSNWT 1988, c C-17; the Cost of Credit Disclosure Act, SNWT 2010, c 23;

- Nunavut: the Consumer Protection Act, RSNWT (Nu) 1988, c C-17.

Banks governed by the federal Bank Act (and other federally regulated entities) may take the position that they are not required to comply with provincial laws. However, the Supreme Court of Canada has repeatedly undermined this position in several distinct situations (eg, see Bank of Montreal v Marcotte, 2014 SCC 55). While it is incorrect to say that federally regulated banks are not subject to provincial laws, the extent to which they need to comply with provincial laws is unclear. Provincial laws regulate private dealings within the province and between residents of the province. Accordingly, banks must comply with provincial laws to the extent required to carry on their business within each province. It would therefore be prudent for banks to comply with the requirements of consumer protection legislation where possible.

Provincial consumer protection legislation sets out both general rules applicable to all interactions with consumers (eg, prohibitions regarding unfair practices) and detailed rules that regulate how specific consumer agreements, including credit agreements, are to be carried out. See question 6.1(b) for additional detail on the applicability of consumer protection legislation to consumer credit.

Although consumer protection legislation is substantially similar across provinces and territories, the specific language of each applicable act should be consulted for the particular requirements in each province.

10.2 How are deposits protected in your jurisdiction?

Federally, the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC) protects deposits. The CDIC is a federal crown corporation that provides deposit insurance against the loss of eligible deposits at member financial institutions up to C$100,000. Members of the CDIC include federally regulated deposit-taking institutions, including banks, federally regulated credit unions, and loan and trust companies and associations governed by the Cooperative Credit Associations Act, SC 1991, c 48. The terms and conditions of CDIC deposit protection are set out under the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation Act, RSC 1985, c C-3 and its regulations.

The province of Quebec has its own deposit insurance plan under the administration of l'Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF). Financial institutions that are members of both the CDIC and AMF plan are subject to an agreement between the two insurers that requires that deposits made in Quebec with provincially incorporated CDIC members are insured by AMF, and deposits made outside of Quebec with AMF members are insured by CDIC.

In addition, provincial deposit insurance plans cover deposits with regard to provincially regulated credit unions, caisses populaires, or trust and loan companies. For example, in Ontario, the Deposit Insurance Corporation of Ontario, established under the Credit Unions and Caisses Populaires Act, 1994, SO 1994, c 11, protect depositors of Ontario credit unions and caisses populaires from loss of their deposits. Deposit insurance plans vary between the ten Canadian provinces and customers should contact provincial deposit insurers directly to determine how deposits are protected through these various plans.

11 Data security and cybersecurity

11.1 What is the applicable data protection regime in your jurisdiction and what specific implications does this have for banks?

In Canada, the Federal Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, (PIPEDA), applies to the collection, use and disclosure of personal information in the course of commercial activity, and personal information regarding employees of federal works or undertakings, including banks. Under PIPEDA, 'personal information' includes any information "about an identifiable individual". This includes information where there is a serious possibility it can identify an individual.

PIPEDA is based on fair information principles, including accountability, consent, limiting collection, use, disclosure and retention of personal information, and security.

When collecting, using or disclosing personal information, subject to prescribed exceptions, PIPEDA requires the informed consent of the individual. For the consent to be valid, it must be reasonable to believe that the individual understands the "nature, purpose, and consequences" of what they are agreeing to. In recent Guidelines for Obtaining Meaningful Consent", the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) emphasised that to obtain consent, individuals must be provided with clear information emphasising:

- what personal information is being collected;

- the purposes for which the personal information is being collected, used and disclosed;

- what third parties the personal information may be shared with; and

- any associated risk of harm.

Organisations are responsible for information under their control, and must implement physical, technological and organisational security appropriate to the sensitivity of the information. Highly sensitive information, including financial information, will require higher security.

Where an organisation experiences a breach of its safeguards resulting in a "real risk of significant harm to an individual", there is a requirement to report the breach to the OPC, the affected individuals and any organisation that may reduce the risk of harm.

11.2 What is the applicable cybersecurity regime in your jurisdiction and what specific implications does this have for banks?

PIPEDA applies to the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information in commercial activity, regardless of the medium in which such processing occurs. PIPEDA will apply to personal information collected or processed though digital means.

PIPEDA requires organisations to implement security for personal information in their control that includes physical, organisational and technological measures, and that is appropriate to the sensitivity of the information. Where personal information is in electronic form, technological security will be particularly important, including measures such as encryption and access logging. Relevant industry standards, including the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, must also be considered.

Federally regulated financial institutions, including banks, are also subject to the requirements of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI). OSFI has issued guidelines on cybersecurity, including Cyber Security Self-Assessment Guidance and Technology and Cyber Security Incident Reporting Requirements.

The OSFI self-assessment guidance sets out key properties of a cybersecurity programme that organisations can assess themselves against. The assessment includes consideration of:

- the organisation's accountability and ownership of its cybersecurity program;

- whether it has implemented processes to review the risks it faces;

- the situation within the organisation with respect to its users, devices and applications;

- whether it has implemented controls to detect and prevent data loss and to rapidly respond to cybersecurity incidents; and

- the organisation's governance policies and practices.

The Cyber Security Incident Reporting Requirements oblige institutions to report to OSFI if they experience a technology or security incident they determine is reaches a "high or critical security level". The organisation must consider factors including:

- the incident's potential operational impact;

- its impact on customer data;

- disruption to business systems;

- potential for negative reputational impact;

- potential effect on other financial institutions or the Canadian financial system; and

- whether the matter has been reported to other regulatory authorities.

These requirements will apply in addition to those to which the institution may be subject under PIPEDA.

12 Financial crime and banking secrecy

12.1 What provisions govern money laundering and other forms of financial crime in your jurisdiction and what specific implications do these have for banks?

The Canadian regime covering anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF) is established in accordance with the following AML and CFT legislation:

- the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA);

- the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Suspicious Transaction Reporting Regulations;

- the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Regulations;

- the Cross-Border Currency and Monetary Instruments Reporting Regulations;

- the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Registration Regulations;

- the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Administrative Monetary Penalties Regulations; and

- the Criminal Code.

In addition, banks abide by guidance issued by the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) which enforces the PCMLTFA and its regulations.

AML/CTF policies and procedures for banks are also designed to achieve compliance with all Canadian sanctions laws and regulations, including the following:

- the United Nations Act;

- the Special Economic Measures Act;

- the Freezing Assets of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act; and

- the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act.

The PCMLTFA requires a bank to:

- apply know your client measures to all persons who open an account or otherwise enter into a business relationship with the bank;

- conduct regular AML and CFT risk assessments to identify risks in its operations and identify areas that must be reviewed and possibly changed;

- monitor transactions and submit suspicious transaction reports to FINTRAC where the bank has reasonable grounds to believe that money laundering, terrorist financing or illicit behaviour has been committed or attempted, or is about to be committed. The bank must also submit reports to FINTRAC with respect to certain transactions or assets based on the regulations under the PCMLTFA;

- maintain records relating to its customer transactions and the measures taken to comply with the requirements of the PCMLTFA; and

- ensure that international funds transfers (outbound and inbound, to the extent possible) and SWIFT messages in Canada contain originator information.

12.2 Does banking secrecy apply in your jurisdiction?

Canada does not have specific legislation governing bank secrecy. However, if banks collect customer data in Canada, they must comply with certain laws, which include:

- the common law duty of confidentiality (and in Quebec the civil law obligation to respect privacy), which banks owe to their customers;

- the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (SC 2000, c 5); and

- certain provisions of the Bank Act which protect disclosure of customer data in certain situations and ensure that communication between banks and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions is strictly confidential.

13 Competition

13.1 What specific challenges or concerns does the banking sector present from a competition perspective? Are there any pro-competition measures that are targeted specifically at banks?

The criminal prohibitions, civil reviewable practices and merger review provisions of the Competition Act apply generally with equal force and effect to all sectors of the Canadian economy, including banking. The act also specifically prohibits in Section 49 certain agreements or arrangements between federal financial institutions, such as the kinds of services provided to a customer and the charges for such services, while setting out a number of exemptions, including for joint customers where the customer has knowledge of the agreement.

Banking in Canada is highly regulated. This has been credited as creating one of the soundest financial systems in the world, but has also raised concerns - including from Canada's Competition Bureau - as it limits competition, innovation and consumers' choices. For example, foreign ownership restrictions have been criticised for insulating the Canadian banking sector from outside competitive pressures.

The financial services sector has recently emerged as a significant area of focus for the bureau's advocacy initiatives. In December 2017 the bureau published an extensive market study on fintech. The study focused on three broad service categories:

- retail payments and the retail payments system;

- lending and equity crowdfunding; and

- investment dealing and advice.

It resulted in 30 recommendations to regulators and policy makers for fostering innovation. More recently, in February 2019 the bureau submitted a response to the Department of Finance's public consultation on the topic of open banking, asserting that greater financial technology adoption would promote competition among banks and likely result in a broader range of services for consumers. Another area of keen interest for the bureau has been 'big data' and the oversight of companies that collect and use consumer data, including banks. The bureau released a discussion paper on the topic in September 2017, followed by a final report in February 2018 that summarised its enforcement approach.

14 Recovery, resolution and liquidation

14.1 What options are available where banks are failing in your jurisdiction?

The mandate of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) includes monitoring the viability of Canadian banks and conducting risk-based assessments to identify where increased supervision or corrective action or intervention is required. Where a bank is identified as experiencing difficulties, there are a variety of flexible tools available to address the situation.

The last resort of a failing bank is winding-up under the Winding-up and Restructuring Act. However, the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC) Act establishes CDIC as the resolution authority for regulated deposit-taking institutions, including banks. In addition to insuring deposits, CDIC has available to it a variety of tools to resolve a failing bank. CDIC may, for example:

- take temporary control or ownership of a failing bank;

- sell of otherwise dispose of a failing bank's assets;

- transfer certain the failing bank's assets and deposits to a 'bridge institution';

- convert preferred shares and debt to equity by way of a 'bail-in' transaction; and/or

- cause a failing bank to engage in a restructuring transaction or transactions.

CDIC may also be appointed as the receiver of a bank.

Banks that are designated by OSFI as being systemically important, which include Canada's six largest banks, must prepare a resolution plan that is reviewed and, if necessary, implemented by CDIC.

Canada has endorsed the Financial Stability Board's (FSB) Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions and CDIC's approach to the resolution of failing banks is aligned with the FSB's Key Attributes.

14.2 What insolvency and liquidation regime applies to banks in your jurisdiction?

The Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act and the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act - the standard legislation in Canada applicable to the liquidation and reorganisation of insolvency businesses - do not apply to banks. The only formal insolvency liquidation procedure that is available to an insolvent bank in Canada is winding-up under the Winding-up and Restructuring Act. This act does not include any mechanism by which an insolvent bank can be reorganised.

15 Trends and predictions

15.1 How would you describe the current banking landscape and prevailing trends in your jurisdiction? Are any new developments anticipated in the next 12 months, including any proposed legislative reforms?

Bill C-86 will introduce a comprehensive financial consumer protection framework to the Bank Act . Its entry into force has yet to be determined and we expect detailed regulations to be elaborated in many broad areas as permitted by the bill . The framework establishes new rules for fair and equitable dealings with customers and the public, with a focus on:

- sales practices, product suitability, remuneration relating to sales and application of the rules when products and services are offered by affiliates;

- opening and operation of retail deposit accounts;

- consumer lending, including provisions relating to mortgage renewals, credit cards and other consumer credit;

- prepaid payment products and charges and the requirement for express consent;

- optional products and the requirement for express consent; and

- complaints and designated complaints bodies.

In certain cases where a bank has imposed charges or penalties that are not provided for in or are contrary to an agreement, or that concern a product or service no expressly consented to, the bank is required to refund the amounts plus interest . The framework sets out separately revised disclosure requirements that apply to banks which must be made "using language, that is clear, simple and not misleading" and in writing, unless permitted otherwise by this part of the framework. Once in force, banks will be required to disclose information boxes on its application forms and agreements with customers . Particular disclosure rules (some of which are new; others which are similar to the current requirements) are provided for:

- deposit accounts;

- deposit insurance and mortgage insurance;

- deposit-type instruments and principal protected notes;

- credit agreements;

- prepaid payment products;

- product renewals and optional products and services; and

- advertising.

The bill also establishes a whistleblowing regime for employees of banks to report wrongdoing, including contraventions of:

- the Bank Act and its regulations;

- the voluntary codes of conduct that the bank has committed to adopt; and

- the policies or procedures of the bank.

In addition, the Bank of Canada has signalled an interest in innovation in the banking market, which has included investigations and considerations of digital currency, open banking and similar tools. Payments Canada, which operates the Canadian payment system, is in the midst of a multi-year modernisation. The replacement of the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate as an offering rate has led the Bank of Canada to indicate support for a replacement for the Canadian Dollar Offering Rate using an overnight repo rate.

The recent Canada-Mexico-US trade agreement also contains provision for increased cross-border banking activity, including cross-border data flows.

15.2 Does your jurisdiction regulate cryptocurrencies? Are there any legislative developments with respect to cryptocurrencies or fintech in general?

Although Canada allows the use of cryptocurrencies, the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada has provided guidance that cryptocurrencies are not considered to be legal tender in Canada; only the Canadian dollar is considered official currency in Canada. The Currency Act defines 'legal tender' to mean "bank notes issued by the Bank of Canada under the Bank of Canada Act" and "coins issued under the Royal Canadian Mint Act".

The Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) - the collective of Canada's provincial securities regulators - along with the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada, is drafting a regulatory framework applicable to crypto-asset trading platforms as they review the comments and responses to their Joint Consultation Paper 21-402, Proposed Framework for Crypto-Asset Trading Platforms. They anticipate publishing a summary of comments and responses along with guidance on the regulatory framework later this year.

Additionally, on 16 January 2020, the CSA issued CSA Staff Notice 21-327, Guidance on the Application of Securities Legislation to Entities Facilitating the Trading of Crypto Assets. The guidance provides that a cryptocurrency exchange operating in Canada or serving Canadian users is likely subject to Canadian securities legislation.

In January 2019 the Minister of Finance Advisory Committee on Open Banking conducted a first phase review on the merits of open banking, in which it identified a need for the development of more secure infrastructure to use and move financial data. In second phase, the committee will continue its work on open banking (which it prefers to call 'consumer-directed finance') with stakeholders, to consider potential solutions and standards to enhance data protection such as Canada's Digital Charter, consumer protection in the financial sector and cybersecurity. In January 2020 the Bank of Canada noted that getting to grips with digital currency would be on the Bank of Canada's agenda for the year, continuing prior investigations into this subject matter.

16 Tips and traps

16.1 What are your top tips for banking entities operating in your jurisdiction and what potential issues would you highlight?

Financial regulation is complicated and this tends to be the case in most jurisdictions. On the other hand, in our experience, the objectives of regulators are straightforward and transparent: protecting the public and their confidence in the Canadian financial system and financial markets. Regulations are protective of foreign entries into the Canadian market without compliance with law. With this in mind, we encourage financial institutions to engage proactively in dialogue with regulators.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.