The EU AI Act - and what it means for most companies

Much has already been written about the "AI Act" - critics see it as a regulatory monster, while its creators praise it as a shining example of global AI regulation that will promote innovation. But how does the AI Act actually work? Who does it even apply to – including outside the EU? And how do companies need to prepare? We answer these questions in part 7 of our AI series.

First of all, the AI Act (AIA) has not yet been adopted at the time of writing. Following the political agreement last autumn, the proposal for the "final" text has been available since the end of January, and most recently the EU Council of EU Ministers approved the Act on February 2nd, 2024 (this version is available here). Formal adoption by the EU Parliament is currently not expected until April. The current text is also still a draft that needs to be finalised. In particular, the recitals and articles will have to be renumbered throughout (which is why they are not referenced here). Material changes are no longer expected, though.

1. Concept

Like the GDPR, the AIA is a regulation, i.e. directly applicable EU law. Enforcement takes place both locally in the member states (each of which must designate a market surveillance authority and an authority to regulate the procedures of the bodies assessing product conformity) and centrally (for example, the EU Commission is responsible for general purpose AI models).

As with the GDPR, there are also central institutions such as the European Artificial Intelligence Board (EAIB), for which each member state appoints a delegate. A "Scientific Panel of Independent Experts" is to be created, as well as the central "AI Office" as part of the European Commission, which will support the market surveillance authorities, but will also, for example, provide certain templates and monitor certain topics such as copyright compliance in connection with AI models. The European Commission as such also has supervisory tasks.

Whether and when the EEA states will also adopt the AIA is not yet clear.

It is not yet clear whether and when the AIA will apply not only to EU Member States but also to EEA States. The AIA applies to private organisations as well as public authorities, but not to military, defence and national security uses of AI, as these areas are still largely reserved for regulation by the member states.

Although the AIA is long (245 pages in the current draft) and, like almost every EU legal text, tedious to read, the regulatory concept is not particularly complicated. In a nutshell:

- First, a distinction is made between "AI Systems" (AIS) and "General Purpose AI Models" (GPAIM).

- The personal and territorial scope of applications is defined, whereby a distinction is made in particular between those who offer AIS and GPAIM ("providers") and those who deploy them ("deployers").

- A few AI applications are banned entirely.

- Some AI applications are defined as being "high risk" ("High-Risk AI System",HRAIS): Certain requirements must be met by an HRAIS (e.g. quality and risk management, documentation, declaration of conformity), compliance is primarily the responsibility of the providers but a few obligations are also imposed on the deployers.

- For all other AIS, some more general obligations are defined for both providers and deployers, mainly for transparency.

- The GPAIM distinguishes between:

- Not recorded at all (very few cases),

- "normal" (with minimal obligations for providers),

- and "Systemic risks" (with additional obligations for providers).

- A distinction is made between GPAIMs that are not covered at all (very few), "normal" GPAIM (with minimal obligations for providers) and those that entail "systemic risks" (with additional obligations for their providers).

- The European Commission maintains a central register of HRAIS and there are various regulations (including reporting obligations) to keep track of incidents related to HRAIS and to respond to such incidents if necessary.

- Accompanying instruments are envisaged, such as

- regulatory sandboxes: (right to involve supervisors in the development of new AIS for early legal certainty),

- regulations/arrangements for testing AIS in the "real world",

- codes of conduct; and

- various provisions for the creation of standards, benchmarks and templates. How relevant they will be in practice remains to be seen.

- There are some enforcement provisions that provide for investigative and intervention powers for market surveillance authorities, administrative fines (usually slightly lower than under the GDPR) and a right of access for individuals in the EU that are affected by negative AI-assisted decisions.

- There are provisions on entry into force and very few transitional provisions.

GPAIM are noticeably milder and less thoroughly regulated than AIS and are also dealt with separately, which is partly due to the fact that they were only included in the AIA after the initial draft had been proposed in mid-2021, i.e. before the hype surrounding ChatGPT & Co. and the Large Language Models (LLM) on which these applications are based. The GPT LLM is a classical example of a GPAIM.

The AIA is primarily a market access and product regulation, as it is familiar for various products with increased risks (e.g. medtech). This is in contrast to the GDPR, which primarily regulates behaviour (processing of personal data) and data subject rights. Although a few general principles of conduct for using AI are defined in the AIA and affected persons are granted one particular "right" to information, these provisions are focused on very specific, limited use cases; even the "prohibited" AI applications are very narrowly defined. Instead, above all, the AIA regulates the accompanying measures that must be implemented in the case of AIS deemed to be particularly risky and how such AIS must be placed on the market, used and monitored.

Some HRAIS will be AIS that are part of already regulated products, in which case many of the obligations provided for by the AIA already apply in a similar way; the AIA regularly refers to them and provides for a coordinated implementation (for example with regard to risk and quality management, documentation and conformity declarations, but also with regard to regulatory supervision). The lawmakers at least tried to limit bureaucracy in these cases; however many question whether they succeeded. Nevertheless, the AIA repeatedly makes it clear that a risk-based approach should apply. Many of the requirements set forth by the AIA are rather generic, which leaves some wiggle room when it comes to their implementation.

The AIA repeatedly states that it applies in addition to existing laws and regulations, i.e. it does not restrict them in any way. This applies in particular to the GDPR. The AIA also does not in itself constitute a legal basis for the processing of personal data, with a few exceptions – namely when it would be "strictly necessary" ("reasonable" is not sufficient) to process special categories of personal data for testing and correcting an HRAIS (but not other AIS) with regard to a possible bias. Beyond that, the AIA contains hardly any provisions that deal with data protection; it is noteable, though, that the EU Data Protection Supervisor is to be assigned the task of AI market supervision over the EU institutions. It remains to be seen to what extent the EU member states will also entrust their AI market supervision obligations to their own existing data protection authorities.

What is also noticeable is that the legislator apparently had some difficulty in regulating the use of AIS by public authorities in the area of law enforcement and specifically in systems for the remote biometric identification of people in public (e.g. based on their faces or gait via cameras in public places). The use of these systems is permitted in certain cases and the AIA regulates this in much more detail than it does any other applications (although it should be noted that the area of national security is completely excluded from the scope of the AIA). Since all this will be less relevant for companies, we will not go into more detail on these and other governmental applications here.

2. Scope of application: What is an AI system?

Unfortunately, the scope of the AIA is anything but clear in various respects – and it is defined in an extremely broad manner.

This starts with the definition of AIS. It contains five elements, three of which apply to almost every IT application, namely that, in simple terms, a system (i) is machine-based, (ii) infers from an input how an output is to be generated, and (iii) this output can have an influence outside the system. This probably applies to any classic spreadsheet or image processing software, as they, as well, generate an output (result of calculations, images processed with filters) inferred from input (numbers and formulas, images) and it can have an influence outside the system.

The other criteria are that (iv) the system may be able to adapt itself after its implementation (the AIA refers to "may", meaning that the system's ability to learn is not a prerequisite) and (v) it is "designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy". This last element of the definition, i.e. partial or full autonomy, therefore appears to be the only really relevant distinguishing criteria that differentiates AI systems from other IT systems. Still, it is also not entirely clear what "autonomy" means. In our view, it draws a distinction between systems whose output is generated entirely according to rules that have been formulated by humans, i.e. a deterministically or fully statically programmed system ("if-then"-systems) and other systems, i.e. systems that, for example, use pattern recognition based on their training to determine the output. In those cases, the (human) deterministic or static programming no longer or no longer alone determines the output that results from the input. The recitals seem to support this view. While most people think of static code as code written by human programmers, it is also possible that such code has been programmed by an AI. A system with deterministic decision logic and conduct programmed by an AI is therefore not an AIS because it lacks autonomy. This leads to the interesting question of how the AIA regulations could be circumvented in this way, for example by commissioning an AI system to develop a system based on its knowledge that is based on a deterministic programming, but nevertheless so complex that we humans no longer understand its function or decision-making logic. For the time being, however, we have to assume that the applicability of the AIA can, in principle, be prevented by only using systems that do not act autonomously, even if they lead to the same result or do equally problematic things as an AIS.

The definition of GPAIM is even more vague than that of AIS. It does not even state what an "AI model" is. An AI model becomes a "general purpose" AI model if displays "significant generality" and is therefore capable of competently performing "a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market" and can be integrated into a variety of systems and applications.

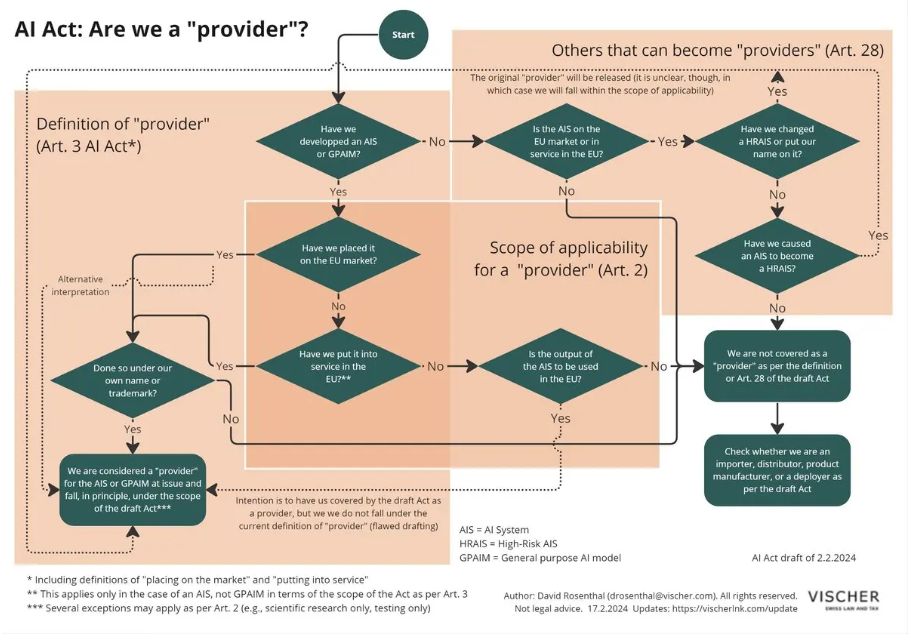

3. Scope of application: Who is considered a provider?

As already mentioned, the two most important roles in which an organisation can become subject to the AIA separately or simultaneously are that of the provider and the deployer. Although there are other roles such as importers, distributors and product manufacturers as well as the EU representative, they ultimately be attributed to the provider. The market surveillance authorities can take action against all of them, and all of them must co-operate with the authorities.

It is essential that an organisation identifies its role for each AIS or GPAIM it deals with, as this role will determine its obligations under the AIA. Most of the obligations are imposed on the provider (see below).

The provider is primarily the party that (i) develops an AIS or GPAIM (itself or on behalf of others), and (ii) places it on the market or puts it into service it under its own name:

- "Placing on the market" refers only to the EU market and means the first making available of an AIS or GPAIM on that market.

- "Putting into service" also refers only to the EU. It means the initial supply of an AIS for first use directly to a deployer or for own use by the provider (this second criteria does not apply to GPAIM because under the AIA these models are considered only a preliminary stage of an AIS).

- In both cases, the activities presumably must have been directed towards the EU; a "non-intentional spill-over" to the EU market is not sufficient.

- It does not matter whether the AIS is offered for a fee or free of charge.

Prior to this happening, the research, development and testing on and of an AIS is not subject to the the AIA, with the only exception being field trials, also referred to as testing in the "real world" (there is a separate section in the AIA regulating these trials).

This definition has some implications. Anyone who has developed an AIS and neither places it on the EU market nor supplies it for its own or a third-party use in the EU can, thus, not be considered a provider according to the definition of the AIA, even if the AIS finds its way into the EU or has effects within the EU. This even applies to companies located in the EU. While this seems logical based on the AIA's definition of "provider", it creates a loophole because the AIA's territorial scope has been defined more broadly: According to it, providers located abroad should also be covered if the output of their AIS is by intention used in the EU. This provision was to prevent the circumvention of the AIA by AIS that have effects in the EU but are operated outside the EU. The provision, however, cannot apply to providers because the legal definition of what constitutes a provider already presupposes an EU market connection. It will be interesting to see how the market surveillance authorities deal with this legislative oversight, given that the intention of the legislator is as clear as the contradictory wording.

However, there is one area of application for the aforementioned "anti-circumvention" provisions of the AIA: It applies to those who exceptionally become a provider because they (i) "put" their name or trademark on an HRAIS (whatever this means) that is already on the EU market, (ii) substantially modify such an HRAIS (but it remains an HRAIS) or (iii) modify or use an AIS on the EU market contrary to its intended purpose in such a way that it becomes an HRAIS. An example of the latter is the use of a general purpose chatbot for a high-risk application. The original provider is then no longer considered the provider. In this case, the aforementioned provision will cover such providers if they are based outside the EU, but the output of the AI is used as intended in the EU. If this were not the case, it becomes questionable whether these "secondary" providers still fall within the scope of the AIA if they themselves did not place the AIS on the EU market and have not used it there. This would be yet another loophole in the AIA.

Some legal writers have argued that the AIA directly or indirectly regulates every AIS that affects persons in the EU. According to the view expressed here, this is not the case. It is true that the AIA explicitly applies to all affected persons in the EU. However, this does not automatically mean that it also applies to all providers, deployers and other persons; their personal and territorial scope of application is defined separately and in a distinct manner by the AIA. If every AIS (including its providers, deployers and other persons involved) were automatically subject to the AIA, the differentiations of the rules discussed above would not have been necessary in the first place. Rather, the inclusion of the "affected persons" in the definition of the AIA's scope is necessary so that they can assert their (few) rights under the AIA.

The cases in which an AIS has been created bymore than one provideror where the AIS of one provider contains an AIS of another provider are regulated by the AIA only in a very rudimentary manner. The AIA provides that the provider should conclude a contract with its "sub-provider" that enables the provider to comply with the AIA; the sub-provider will presumably be covered independently pursuant to its own market activities. Furthermore, anyone who places on the EU market or puts into service in the EU an AIS with another product, is considered a "product manufacturer" under the AIA and – if it is a HRAIS (e.g. because it is a safety component of a regulated product) – will be considered its provider as per the AIA. Hence, not only the person who (i) first develops an AIS can be its provider, but also the person who (ii) further develops it and (iii) incorporates it into a new AIS or other product.

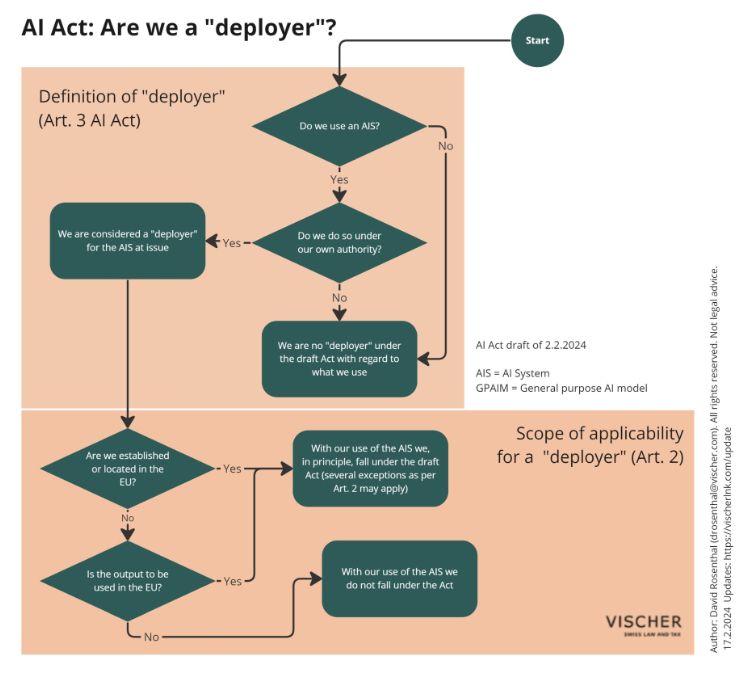

4. Scope of application: Who is considered a deployer?

Business users of AIS are referred to as "deployers" under the AIA and are subject to only a few obligations (see below). A deployer is anyone who uses an AIS under its own authority. Exempt are those persons who use an AIS only for personal, non-professional activities (although here, too, the drafting of the AIA was somewhat careless – this exception exists on two levels, but is (at least still) formulated slightly differently).

The criterion "under its authority" in our view distinguishes the mere "enjoyment" of an AIS and its output from the use of an AIS as a tool under its own control. Hence, a certain degree of control will be required for the criterion to be met. If a user uses a customer service chatbot on a website, they do not have this control; at least no such control is intended. They can ask questions and the company controls how the chatbot answers them. It would only be different if the user managed to "hack" the chatbot and cause it to make unintended statements. If, on the other hand, a company provides its customers with an AI functionality as part of a service that they can and should control for their own purposes within certain limits, then the "under its authority" criterion is likely to be met in our view. If a company such as OpenAI offers its customers the chatbot "ChatGPT", this differs from the customer service chatbot mentioned above in that it is the OpenAI customer who should instruct the chatbot what to talk about and no longer the company that operates it. Where exactly the line is to be drawn (e.g. in the case of expert chatbots) is, of course, not yet clear.

The territorial scope of the AIA covers all those deployers who are either in the EU (whether with an establishment or because they reside there as natural persons) or, if they are not in the EU, as soon as the output of the AIS they operate is "used" in the EU. According to the recitals, the latter rule is intended to prevent circumvention of the AIA by providers in third countries (such as Switzerland or the USA) who collect data in the EU or receive it from there, process it with AIS in countries outside the EU and send the result back to the EU for use without the AIS being placed on the market or put into service in the EU. The example itself raises questions, as a company based in the EU that asks a company in another EU country to process data with an AIS on its behalf will probably still be considered its deployer, just as the actions of a processor are attributed to the controller in the area of data protection. The exemption is likely to be much more relevant for those companies that are located in other countries outside the EU (e.g., Switzerland or the USA) and use AIS for themselves. Either way, the AIA is intended to protect natural persons affected by the use of AIS within the EU. According to the recitals, it is necessary that the use of the AI output in the EU was intended and not merely coincidental.

What exactly counts as "use" of AI output in the EU is not specified in the AIA. Whether it is sufficient that the AI output merely has an effect on persons in the EU is a conceivable interpretation, but in our view rather questionable. Some examples:

- Anyone who publishes AI-generated content on a non-EU-website that (also) targets users in the EU audience is likely to be covered by the rule.

- Companies that send texts generated by an AIS to customers in the EU are also likely to be covered.

- If a document created by an AIS outside the EU somehow finds its way into the EU by chance, then the rule should not apply to the deployer of the AIS.

- The use of an HRAIS or the implementation of a practice prohibited under AIA by a Swiss employer in relation to its Swiss employees should not become subject to the AIA according to the rule even if employees living in the EU are effected, provided that the Swiss employer makes use of the AIS' output only at the company's offices in Switzerland.

- However, if the employer uses a cloud provider located in the EU for storing the output, the legal situation may be different. Yet, it is still unclear whether the outsourcing of the operation of an AIS to a provider based in the EU or a provider using a data centre in the EU will mean that the output of the AIS is deemed to be "used" there. We do not believe that this is the case: In view of the purpose of primary purpose of protection, namely the protection of the health, safety and fundamental rights of natural persons in the EU (only they are in focus), the outsourcing of IT operations to the EU as such cannot be sufficient. There is no connection to the persons affected. Also, the mere commissioning of a service provider in the EU does not constitute an establishment in the EU (nor does it under the GDPR). The secondary protection objectives of the AIA also include the protection of democracy, the rule of law and the environment, but even these do not really justify an extension of the scope; in terms of the environmental protection objective, the energy consumption of data centres for AI would most likely come into question, but the AIA itself does not contain any really relevant provisions in this respect.

Irrespective of the remaining uncertainties, the regulation of the use of AIS output in the EU leads to a significant extraterritorial effect of the AIA. This means that many Swiss companies should also be concerned with complying with the transparency obligations that are imposed upon deployers under the AIA. With regard to a possible role as a provider, however, they can take the position, as mentioned above, that they are not covered if they neither placed the AIS on the EU market nor put it into service in the EU.

5. Further distinctions that may be relevant in practice

The above AIA definitions raise further issues, particularly where companies develop AIS themselves, use them for interactions with third parties or pass them along within a group of companies.

First, it is unclear what constitutes "developing" an AIS. For example, is this criteria already met if a company parameterises a commercial AI product for its own application (e.g., providing it with corresponding system prompts), fine-tunes the model or integrates it into another application (e.g., by integrating chatbot software offered on the market into its own website or app)? If this were the case, then many users would become providers themselves, as the legal definition of provider also covers those who use AIS for their own purposes, provided that this use takes place in the EU as intended and under their own name. Although such a broad understanding is not correct in our view, it is to be feared that the market surveillance authorities will take a broad view and at least consider as development those actions that go beyond prompting, parameterisation and the provision of other input. This means that fine-tuning of the model of an AIS would be deemed further developing the AIS, whereas the use of "Retrieval Augmented Generation" (RAG) would not. It would also be possible to argue that a distinction should be made based on the risk posed by the contribution in each case, but doing so would lead to considerable legal uncertainty, as the same action would result to the person acting being qualified differently depending only on the purpose of the system. It should be noted that the deployer in any event remains liable to a certain extent.

Until the legal situation has been clarified, companies are advised as a precautionary measure to also state the name of their technology supplier externally when using such AIS (e.g. "Powered by ..." for a chatbot that is offered to their own customers as a service on their website). This way, it can be argued that the AIS – even if the implementation or fine-tuning were considered a development – is not used under the user's own name or trademark. Another possible precautionary measure is to restrict the authorised use of an AIS to persons outside the EU, as the legal definition of the provider would then presumably no longer apply.

It is also unclear how the transfer of AI services or AI technology within a group of companies should be assessed. Various tricky scenarios are conceivable here. One scenario is the case in which group company X outside the EU purchases an AIS from provider Y outside the EU and then makes it available to other group companies in the EU. If the AIS has not yet been placed on the EU market or put into service in the EU, X can be deemed its "distributor" or even "importer" without having further contributed to its development. This would entail a number of special obligations. While X can probably prevent being classified as an importer (and provider) by only passing along AIS to the EU that already are on the EU market, this does not protect X from being classified a distributor. It can at least be argued that the legal term presupposes that the company is part of the "supply chain" of Y mentioned in the definition and that this does not reasonably entail any intra-group distribution of an AIS to group companies of X.

In the corporate context, the question may also arise as to the point at which a company that makes aproduct with AI-supported functionality available to its customersis itself considered a provider and the customers are considered deployers. The hurdles are not very high: Take the example of a bank outside the EU that offers its EU business customers an AI-supported analysis of their portfolios in its online banking and trading application, being part of the bank's commercial service. If the bank has developed this functionality itself or has had it developed, it will already be considered a provider due to its own use, especially since it uses it in the EU and does so under its own name.

The customers who use the AI analysis function can in turn become deployers and be subject to the AIA, even if the bank itself does not care about the AIA. Two conditions must be observed here: First, the customers must be located in the EU or the output of the AI analysis must be used in the EU. Second, they must use the AI function under their authority (see above). If the bank client (business client do not fall under the AIA exception for personal, non-professional use) thus obtains the necessary control over the AI function, it will have to ensure (and want to ensure) under its own responsibility that it is not engaging in a prohibited AI practice and that any applicable deployer obligations are complied with. The difficulty in practice may be that EU deployers may not even know where and when AIS are used in the products and services they use, if the providers of these products and services are from outside the EU.

In this context, the question may also arise as to whether a provider can logically only exist if there is also a deployer to which the provider makes the AIS available. The answer to this is probably "no". Otherwise, all providers that only offer AI services to consumers in the EU would not be covered by the AIA because such users are not considered deployers by virtue of an exemption. The definition of provider does not require a deployer: On the one hand, it is sufficient to put into service an AIS for own use in the EU. In order to fulfil this, it is presumably sufficient for the provider to target users in the EU and let them use the AIS as a service (it will be considered the provider's use own of the AIS because it remains the provider's service even from a user's perspective). On the other hand, the alternative criterion for qualifying as a provider under the AIA (the "making available on the market") is fulfilled if an AIS is supplied "for ... use on the Union market in the course of a commercial activity", which will likely be assumed to be the case here. However, this question has not been conclusively clarified either.

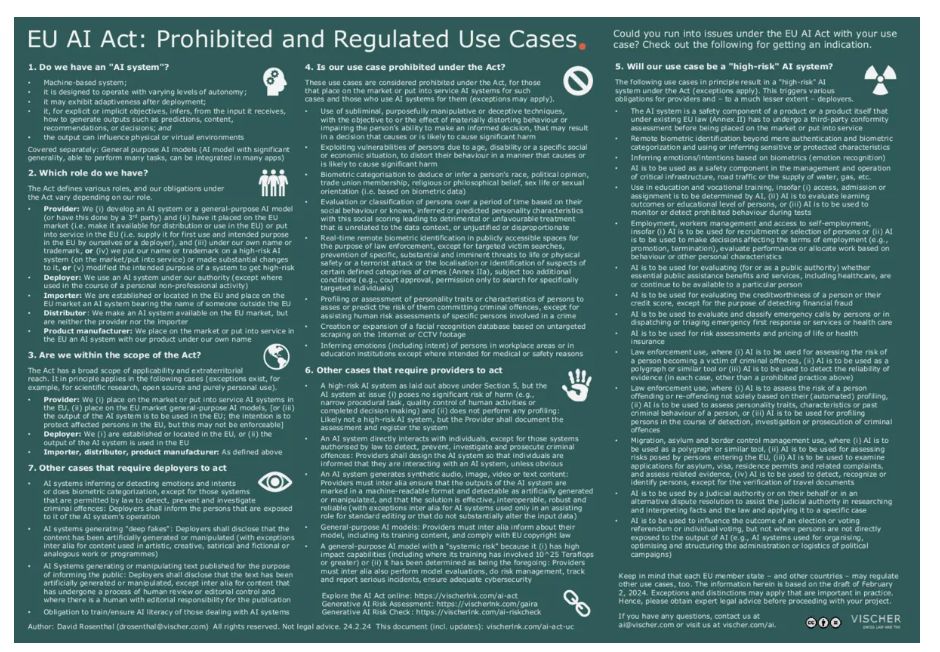

6. Prohibited AI applications

Eight specific "AI practices" are completely prohibited under the AIA. In most cases, the ban covers all those who place the AIS in question on the market in the EU, put it into service in the EU or simply uses it (which, as shown, also includes those who use them abroad, provided that the output of the AIS is also used in the EU as intended).

The list of prohibited AI practices is very specific:

- Use of subliminal, purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques, with the objective or the effect of materially distorting behaviour or impairing the person's ability to make an informed decision, that may result in a decision that causes or is likely to cause significant harm

- Exploiting vulnerabilities of persons due to age, disability or a specific social or economic situation, to distort their behaviour in a manner that causes or is likely to cause significant harm

- Biometric categorisation to deduce or infer a person's race, political opinion, trade union membership, religious or philosophical belief, sex life or sexual orientation (i.e. based on biometric data)

- Evaluation or classification of persons over a period of time based on their social behaviour or known, inferred or predicted personality characteristics with this social score leading to detrimental or unfavourable treatment that is unrelated to the data context, or unjustified or disproportionate

- Real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces for the purpose of law enforcement, except for targeted specific potential victim searches, prevention of specific, substantial and imminent threats to life or physical safety or a terrorist attack or the localisation or identification of suspects of certain defined categories of crimes (Annex IIa), subject too additional conditions (e.g., court approval, permission only to search for specifically targeted individuals)

- Profiling or assessment of personality traits or characteristics of persons to asses or predict the risk of them committing criminal offences, except for assisting human risk assessments of specific persons involved in a crime

- Creation or expansion of a facial recognition database based on untargeted scraping on the Internet or CCTV footage

- Inferring emotions (including intent) of persons in workplace areas or in education institutions except where intended for medical or safety reasons

It should be noted that these practices are only prohibited if they are carried out using an AIS. For example, anyone who carries out emotion recognition in the workplace solely on the basis of self-programmed "if-then" rules (i.e. no pattern recognition) is not covered. Moreover, the practices are formulated very specifically, so that exceptions quickly arise. For example, the use of AIS to catch students cheating in an exam is not covered by the prohibition on emotion recognition (although this is a high-risk application).

As a further example, anyone who uses an AIS to carry out "data loss prevention" (DLP) is not carrying out a prohibited practice, even if the theft of data can be a criminal offence and DLP can therefore be seen as including an assessment of the risk of a criminal offence in the broadest sense. Yet, because the intended purpose is not the assessment such risks, but the prevention of an unintentional loss of data, the prohibition does not apply, regardless of whether there is a criminal offence (moreover, the prohibited practice no. 6 above is aimed at "predictive policing" and not at the prevention of offences in progress).

Another example: In the case of prohibited practice no. 1, it is not enough for people to be manipulated by means of AI. It must also be done for the purpose of significantly influencing their behaviour, preventing them from making informed decisions, and it must also lead to a decision that can cause significant harm to the person. The recitals even state that "common and legitimate commercial practices" in the area of advertising, which are also otherwise lawful, are not covered here. The case is somewhat less clear with practice no. 4 (scoring), which can be understood quite broadly because it merely presupposes unfavourable treatment. However, the prohibition only applies if the data has nothing to do with the treatment in question or if the unfavourable treatment is disproportionate or unjustified. It will be interesting to see whether, for example, AI-supported functions to calculate the "sweet spot" price for each visitor of an online shop based on their behaviour will be covered. One way to avoid the prohibition would be to use a system that does not make judgements autonomously, but according to clearly predefined rules.

In the case of practice no. 4, the question remains whether and when it refers to AI-based credit scoring and would therefore prohibit it. Although a person's ability to pay is not a social behaviour or a personal characteristic, their willingness to pay can be. This would therefore cover anyone who places an AIS on the market which, for the purpose of determining whether credit should be granted to a person, identifies correlations between a person's behaviour and their presumed unwillingness to pay, using data from a context that has nothing to do with the person's willingness to pay or where the data usage would be disproportionate or unjustified. To counter this, the credit scoring solution provider would, of course, argue that its solution is not intended to answer the question whether a person is willing to pay, but whether it will likely pay or not. Yet, the assessment whether someone is "more likely than not to pay their bills" could arguably be understood as a "social score". If this were the case, it would have to be demonstrated that only data collected in the context of paying bills has been used to make the assessment and that the credit scoring is actually reasonably accurate and the consequences are justifiable. Notably, such an application would nevertheless be covered as a HRAIS (see below).

7. High-risk AI systems

Two types of AIS are considered "high-risk AI systems" (HRAIS). First, HRAIS are in principle all AIS that are products for which current applicable EU regulations already require a third-party conformity assessment, and all AIS used as a safety component of such products (the term "safety component" also includes those AIS whose failure can lead to a risk to the health or safety of people or property). The relevant EU regulations are listed in an annex to the AIA. In these cases, the requirements of the AIA supplement the rules that already apply to these products.

Second, all AIS listed in a further annex to the AIA are considered HRAIS, too. As with the prohibited practices, these AIS are defined very specifically, which is why the list will be regularly reviewed and amended if necessary. The list currently includes the following applications (the decisive factor in each case is whether an AIS is intended to be used for the purpose described). The annex in question usually starts with defining the area of application and then described the specific cases that are to be covered (and any exceptions):

- Remote biometric identification beyond mere authentication and biometric categorization and using or inferring sensitive or protected characteristics

- Inferring emotions or intentions based on biometrics (emotion recognition)

- AI is to be used as a safety component in the management and operation of critical infrastructure, road traffic or the supply of water, gas, etc.

- Use in education and vocational training, insofar (i) access, admission or assignment is to be determined by AI, (ii) AI is to evaluate learning outcomes or educational level of persons, or (iii) AI is to be used to monitor or detect prohibited behaviour during tests

- Employment, workers management and access to self-employment, insofar (i) AI is to be used for recruitment or selection of persons or (ii) AI is to be used to make decisions affecting the terms of employment (e.g., promotion, termination), evaluate performance or allocate work based on behaviour or other personal characteristics

- AI is to be used for evaluating (for or as a public authority) whether essential public assistance benefits and services, including healthcare, are or continue to be available to a particular person

- AI is to be used for evaluating the creditworthiness of a person or their credit score, except for the purpose of detecting financial fraud

- AI is to be used to evaluate and classify emergency calls by persons or in dispatching or triaging emergency first response or services or health care

- AI is to be used for risk assessments and pricing of life or health insurance

- Law enforcement use, where (i) AI is to be used for assessing the risk of a person becoming the victim of criminal offences, (ii) AI is to be used as a polygraph or similar tool or (iii) AI is to be used to detect the reliability of evidence (in each case, other than a prohibited practice above)

- Law enforcement use, where (i) AI is to assess the risk of a person offending or re-offending not solely based on their (automated) profiling, (ii) AI is to be used to assess personality traits, characteristics or past criminal behaviour of a person, or (iii) AI is to be used for profiling persons in the course of detection, investigation or prosecution of criminal offences

- Migration, asylum and border control management use, where (i) AI is to be used as a polygraph or similar tool, (ii) AI is to be used for assessing risks posed by persons entering the EU, (iii) AI is to be used to examine applications for asylum, visa, residence permits and related complaints, and assess related evidence, (iv) AI is to be used to detect, recognize or identify persons, except for the verification of travel documents

- AI is to be used by a judicial authority or on their behalf or in an alternative dispute resolution to assist the judicial authority in researching and interpreting facts and the law and applying it to a specific case

- AI is to be used to influence the outcome of an election or voting referendum or individual voting, but not where persons are not directly exposed to the output of AI (e.g., AI systems used for organising, optimising and structuring the administration or logistics of political campaigns)

Cases 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9 will be of particular relevance for companies in the private sector.

The following one-pager provides an overview of these and the other use cases and definitions of the AIA discussed above:

Where such an HRAIS exists, its provider has a whole range of tasks to fulfil, because it is primarily responsible for ensuring that the requirements set forth in Chapter 2 of the AIA are met by such HRAIS. These< strong>requirements for HRAIS are:

- Comprehensive risk management must be ensured, which means that in particular risk assessments are to be done and repeated over the entire lifespan of the HRAIS, supported by corresponding tests of the HRAIS and combined with the implementation of measures to mitigate the identified risks (see our GAIRAtool);

- The data used for training, verification and testing must fulfil certain quality criteria;

- Detailed technical documentation for the HRAIS must be created and kept up-to-date;

- The HRAIS must automatically record the events that occur in logs for the purpose of monitoring its correct functioning over time;

- The HRAIS must be supplied with instructions for use and designed in such a way that its users can handle it correctly, understand and assess its output adequately and that they can monitor and control the HRAIS (human oversight);

- The HRAIS must be reasonably accurate and robust (it is envisaged that the European Commission has to promote the development of appropriate standards) and be resilient regarding errors, faults and inconsistencies

- The HRAIS must have adequate cybersecurity, especially to protect it against attacks from third parties, both in the area of classical information security as well as AI-specific attacks (see part 6 of our blog series).

To demonstrate compliance with these requirements, providers must:

- Have appropriate documentation of their compliance;

- Have a quality management system;

- Keep the logs generated by their HRAIS in use (if they have them);

- Register the HRAIS in an EU database (except those used in the context of critical infrastructure);

- Have a conformity assessment carried out by an appropriate third party;

- Mark the HRAIS with a conformity mark ("CE") and their contact details; and

- Notify the supervisory authorities if a HRAIS poses a risk to the health, safety or fundamental rights of persons affected or if a serious incident occurs.

A HRAIS provider not based in the EU but subject to the AIA must appoint a representative in the EU who has the necessary documentation concerning the HRAIS at hand so that the EU authorities can access them. Interestingly, the representative is itself obliged to resign from the mandate and inform the market surveillance authority if it has reason to consider that the provider is not fulfilling its obligations under the AIA. Importers and distributors of HRAIS also have certain obligations.

Those who "only" use an HRAIS, i.e. their deployers, also have obligations under the AIA. In particular, they must ensure that:

- The HRAIS is used in accordance with the instructions for use;

- The HRAIS is monitored by qualified people;

- The logs automatically created by the HRAIS must be kept for at least six months;

- That the input data is relevant and sufficiently representative in view of the intended purpose of the HRAIS;

- The provider is informed about the operation of the HRAIS as part of its post-market monitoring;

- The market surveillance authority and the provider (and, if applicable, its distributor) are informed if the deployer has reason to consider that the HRAIS poses a risk to the health, safety or fundamental rights of affected persons;

- When an HRAIS is used in the workplace, the employeesconcerned are informed; and

- Affected persons are informed when an HRAIS is used for decisions concerning them, even if the HRAIS is only used in a supporting capacity (this goes further than under the GDPR).

These obligations are not exhaustive. There is a general clause according to which market surveillance authorities have the power to require providers, deployers and other stakeholders to implement further measures – even if HRAIS are used in compliance with the law, should this be necessary to protect the health or safety of affected persons, their fundamental rights or other public interests.

Furthermore, analogous to the GDPR, the AIA provides for a kind of right to information for affected persons in the EU (but not in Switzerland) if a deployer makes a decision based on the output of an HRAIS that has legal or similarly significant effects on the person that are detrimental to their health, safety or fundamental rights. They can then request that the deployer explains to them what role the HRAIS played in the decision and what the key elements of the decision were. This applies to all HRAIS of the 15 categories listed above, with the exception of no. 2. Raising a corresponding claim under the GDPR is also possible; however, data subject rights concerning automated decisions are a bit narrower under the GDPR in that they only relate to fully automated individual decisions.

Due to the extraterritorial application of the AIA for deployers of HRAIS, these obligations may also be relevant for companies outside the EU, even if the provider is not located in the EU but the output of the HRAIS is used in the EU (see above). Whether and how well these obligations can and will be enforced against companies for example in Switzerland is another question. Based on our experience concerning the GDPR, we believe this is rather unlikely as there significant legal barriers preventing this under Swiss law. However, it should not be possible to impose sanctions on the representative who is itself acting properly.

8. Regulation of AI models

It was only late in the legislative process that the AIA was extended to include regulations for providers of certain AI models (the role of the deployer does not exist here). However, only models that can be used for a wide variety of purposes are covered ("general purpose", GPAIM). However, it is not clear exactly how these are to be distinguished from other models. For example, it could be argued that a model for transcription such as "Whisper" or one that is used only for translations is not a GPAIM. However, if a GPAIM is "specialised" in certain topics such as legal issues through fine-tuning, but can nevertheless be used in many ways, it will probably still be considered a GPAIM.

It is clear from the recitals that GPAIM are not only covered in their actual form, i.e. as files, but also where they are offered via an API (programming interface), so to speak in the form of "model-as-a-service". Based on an interpretation of the recitals, they are not considered AIS themselves, i.e. the corresponding obligations do not apply because they lack a user interface (there is no explanation why an API is not considered a user interface). Therefore, if OpenAI offers access to GPT4 via an API in addition to "ChatGPT", it does not have to comply with the AIA requirements for AIS within the scope of such API, whereas "ChatGPT" is considered AIS. Anyone who uses the model in their application (insofar as it is considered AIS) is then subject to the AIS requirements with regard to such application; they then becomes the application's provider because they developed it and used it for themselves. If they place the application on the EU market or put it into service in the EU, the model used therein is also deemed to have been placed on the EU market.

Those who create a GPAIM but only use it internally are not covered by the requirements for GPAIM because they are only deemed to be providers if they place the GPAIM on the market; the "putting into service" trigger referred to in the "provider" definition only applies to AIS and not GPAIM, which is probably due to an oversight (and yet another loophole). According to the recitals, the exceptions should have been defined more narrowly.

GPAIM providers have in particular the following obligations:

- They must maintain and update detailed technical documentation of the model for the attention of the market surveillance authorities.

- They must maintain and update far less detailed documentation of the model for the attention of the users of the GPAIM.

- If they are located outside the EU, they must appoint a representative in the EU.

- They must introduce internal rules to comply with EU copyright law, including the so-called text and data mining ("TDM") regime and the opt-out right it provides for. The TDM regime allows third parties to extract and use content from databases to which they have legitimate access, but gives the owners of the rights to the works contained therein an "opt-out" right. Even independently of the AIA, it is not entirely clear what the TDM regime means for the training of AI models. The new provision of the AIA will make it even more difficult to train AI models, as anyone who wants to offer a GPAIM in the EU will de facto have to comply with EU copyright law when training their model, even if it is not subject to this law. The aim is to prevent, say, a US provider from creating an AI model under a less stringent foreign law and then launching it on the EU market. In other words, for the purposes of GPAIM, the AIA causes EU copyright law to de facto become applicable worldwide, as most providers of GPAIM will want to offer their products also in the EU.

- They must publicly summarise the content they have used to train their models.

Although the AIA releases GPAIM that are made available under a "free and open" licence from the first three obligations described above, it does not release them from the last two. In addition, the term "free and open" (source) license is defined rather narrowly.

Additional requirements apply to GPAIM providers that entail "systemic risks". From the legislator's point of view, a GPAIM poses systemic risks if it is particularly powerful, which in turn is measured by the computing power used to create it. The large LLMs, such as GPT4 from OpenAI, therefore, clearly qualify as GPAIM with systemic risks. However, the AIA is worded openly: Other GPAIMs can also be declared to be GPAIM with systemic risks. Their providers must then additionally evaluate their models with regard to the associated risks, take appropriate measures to address these risks and identify, document and report serious incidents to the market surveillance authorities, including any measures that can be taken in this regard. They must also ensure that GPAIM provide for adequate cyber security.

9. Further obligations for providers and deployers

The AIA also defines some case-specific transparency obligations that apply to all AIS, including those that are not HRAIS. In particular, obligations to mark and label certain AI-generated content are introduced.

Providers must ensure that:

- Persons interacting with an AIS are informed of this fact, unless it is obvious to a reasonable user.

- The text,audio, video and image contentgenerated by an AIS is labelled as AI-generated or AI-manipulated. The labelling must be machine-readable. It is not yet clear how such marks will be implemented in practice, particularly in the case of text (whereas "watermarking" image content is much easier). Although it is not mandatory to offer suitable "AI content detectors" on the basis of these watermarks, these will certainly be offered soon and hopefully more reliable than what is on the market today. Given that AIS is a very broadly defined term, the AIA provides for an exception for AIS that only assist the "standard editing" of content, provided that these tools do not substantially alter the input data provided or the semantics thereof. Providers of automated translation services such as "DeepL" will try to benefit from this exception; the are fully based on generative AI.

Deployers must ensure that:

- Affected persons are informed if they are exposed to AIS for recognising emotions or intentions or classifying them based on biometric characteristics, provided the AIS processes personal data.

- Deep fakes are identified as such, i.e. as being artificially generated or manipulated content; this does not apply to "evidently artistic, creative, satirical, fictional [or] analogous work or programme" insofar such transparency obligations would hamper the display or enjoyment of the work. It will be interesting to see to what extent this exception will also be applied to advertising.

- Published texts on topics of public interest indicate if they have been AI-generated or manipulated – unless the text has been reviewed by a human and a natural or legal person assumes editorial responsibility for its publication.

The above obligations only apply to AIS, not to GPAIM. Accordingly, if OpenAI offers an AIS such as "ChatGPT", it must ensure that AI content is marked and that such marks are machine-readable. If OpenAI offers access to its models via API, though, it does not have to do so. The obligation is then incumbent on the company that uses this API with its own application, which thus becomes an AIS, provided, of course, the company is considered a provider within the meaning of the AIA and falls within its scope because it places the AIS on the EU marketor puts it into service in the EU.

If an AIS does not fall under these provisions, is not a HRAIS and if it does not involve any prohibited AI practice, then there are basically no obligations for providers, deployers and the other stakeholders with regard to the operation of the AIS defined under the AIA. However, the AIA encourages them to voluntarily adhere to codes of conduct that will one day be developed for AIS in order to ensure the adherence to ethical principles, careful treatment of the environment, AI literacy, diversity and inclusion and the prevention of negative effects of AI on vulnerable people. Furthermore, an article that was only added in the course of the deliberations of the AIA provides for a kind of AI training obligation for providers and deployers, i.e. they must ensure to the best of their ability that the persons who deal with AIS are adequately trained in them, are informed about the applicable obligations under the AIA and are aware of the opportunities and risks of AIS ("AI literacy").

Some will find the AIA going surprisingly little further in regulating the use of AIS that are neither HRAIS nor implement a prohibited practice - i.e. the majority of cases in practice. This is despite the fact that numerous international initiatives, declarations and even the Council of Europe's draft AI Convention have repeatedly formulated requirements that have been identified as important for the responsible use of AI, such as the principles of transparency, non-discrimination, self-determination, fairness, prevention of harm, robustness and reliability of AIS, explainability of AI and human oversight (see also our 11 principles). With the exception of selected aspects of transparency, the AIA only requires compliance in the area of HRAIS, and even there primarily from providers. As shown, it does not even allow the processing of special categories of personal data in order to test a "normal" AIS for bias and eliminate it (after all the AIA does not require anyone to do so in the first place). It remains to be seen whether these principles will be enforced in other ways (e.g., via data protection or unfair competition law), via policies and codes of conduct that organizations voluntarily impose on themselves, or not at all.

10. Application in practice

In the following, we have listed some practical examples to show to whom which provision of the AIA can be applied:

|

Case |

Provider subject to the AIA* |

Deployer subject to the AIA* |

|

A company in the EU provides its employees with ChatGPT or Copilot. They use it to create emails, presentations, blog posts, summaries, translations and other texts and to generate images. |

No |

Yes |

|

The company is located in Switzerland. It is intended that people in the EU will also receive some of the AI-generated content (e.g., as emails or texts on the website). |

No |

Yes |

|

A company in the EU has developed an in-house chat tool based on an LLM and uses it internally to create emails, presentations, blog posts, summaries, translations and other texts and to generate images. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

The company is located in Switzerland. It is intended that people in the EU will also receive some of the AI-generated content (e.g., as emails or texts on the website). |

(Yes)1) |

Yes |

|

A company in the EU uses a specialised application offered on the market for the automatic pre-selection of online job applications. |

No |

Yes, HRAIS |

|

A company in the EU uses ChatGPT or Copilot to analyse job applicants' documents for any issues. The results remain internal. |

Yes2), HRAIS |

Yes, HRAIS |

|

The company is located in Switzerland and only jobs in Switzerland will be considered, although applicants living in the EU may also apply for them. |

No |

No3) |

|

A company in the EU provides a self-created chatbot on its website to answer general inquiries about the company. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

The company is located in Switzerland. The website is also aimed at people in the EU. |

Yes1)4) |

Yes |

|

A company in the EU uses the product or service of a third party to provide the chatbot on its website. The company's content is made available to the chatbot in the form of a database (RAG). The company does not disclose the provider of the chatbot on the website. |

(No)5) |

Yes |

|

The company states the name of the provider that has supplied the chatbot that has been implemented on the website. |

No |

Yes |

|

A company in the EU uses an LLM locally to transcribe texts. The Python script used for the task has been obtained from a source on the Internet and implemented without changes. |

(No)6) |

Yes |

|

A company in the EU uses a service from a US service provider that is also offered to customers in the EU to generate avatars for training videos. |

No |

Yes |

Remarks:

- According to the definitions of the AIA, the company is not a provider, but it is clear that the legislative intention was to have the AIA apply to it as a provider.

- This is due to the special rule according to which an AIS becomes a HRAIS if it is used for one of the high-risk applications; in this case, the user becomes the provider.

- There is no use of the AI outputs in the EU, as it concerns jobs in Switzerland only; the nationality or origin of the job applicants should not play a role, at least as long as the AI outputs are not sent to them (which they are not).

- The chatbot is an AIS that is also intended to be used by people who are in the EU. This means that the AIS is also used in the EU or is provided for such purpose in the EU.

- Parametrising an AIS, hooking it up to a database and implementing it within a website should in our view not yet be considered "developing" an AIS; however, the legal situation is not yet clear in that regard.

- It can be argued that adopting the script is equivalent to installing software that has already been developed and, therefore, itself does not constitute development; moreover, the company will not implement it under its own name. If the script is changed, however, the assessment could be a different one.

*The examples are to be understood as a generalised, simplified illustration of the concept, i.e. the assessment may be different in specific individual cases.

11. Enforcement

The AIA uses various authorities at the level of the individual member states and the EU to enforce its requirements. For example, GPAIMs are to be supervised by the European Commission, while the supervision of AIS lies with the member states. The AIA further separately regulates the supervision of conformity assessments and declarations on the one hand and the actual market surveillance on the other hand. The system is made even more complicated by the fact that where market supervision already exists (for regulated products and the financial industry), supervision should continue to be carried out by the existing authorities. If an AIS is, in turn, based on a GPAIM of the same provider (e.g., "ChatGPT"), then the newly created central AI Office of the European Commission is responsible for market supervision. Yet, if such an AIS is used in a way that corresponds to a HRAIS, the national market surveillance authorities are again in charge.

The market surveillance authorities are granted far-reaching powers of investigation and intervention by the AIA. This even includes the right to demand the source code of an AIS. They must investigate an AIS if they have reason to believe that there is a risk to the health, safety or fundamental rights of the affected persons or that an AIS is incorrectly not classified as HRAIS. Formal violations (missing declaration, etc.) must also be prosecuted and, of course, any affected person within the EU can report AIA violations to them.

The national market surveillance authorities are naturally limited to their own territory. It is unclear what responsibilities they have in relation to providers and deployers in countries outside the EU such as Switzerland and the USA. If the market surveillance authorities of the individual member states do not agree over the measures to be taken, the European Commission has to decide.

The AIA naturally also provides for administrative fines. Similar to under the GDPR, they should be "effective, proportionate and dissuasive". Overall, the penalties are somewhat more lenient than those under the GDPR. Only the sanctions for prohibited AI practices are significantly higher at 7% of global annual turnover or EUR 35 million, whichever is higher. Otherwise, the fines are capped at a maximum of 3% or EUR 15 million, or even lower in certain cases. Unlike under the GDPR, the AIA states that the interests of SMEs, including start-ups, should be taken into account, which is reflected, among other things, by a rule according to which the maximum penalty for SMEs is to be determined on the basis of the lower as opposed to the higher of the two maximum fine levels provided for by the AIA in the case of AIS. As under the GDPR, negligent violations of the AIA can and should be sanctioned, as well.

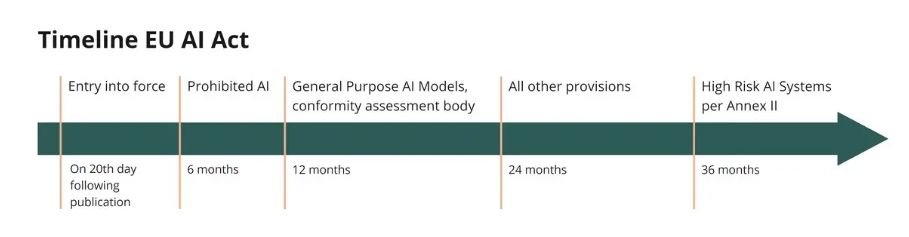

12. Transitional provisions

The AIA formally enters into force on the 20th day following its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. However, its provisions do not generally come into force until 24 months later, with the following exceptions:

- The prohibited AI practices are already banned after six months;

- The regulations on GPAIM and the bodies for performing conformity assessment already apply after twelve months;

- The HRAIS regulations based on existing EU product regulations only apply after 36 months.

As part of the "AI Pact", the European Commission has called on the private sector to implement the AIA already in advance.

In terms of transitional law, no exception applies to prohibited AI practices that existed at the time the AIA came into force.

For HRAIS that were launched on the market before the AIA, the new regulations only apply if and when there are significant changes to their design. For GPAIMs that were introduced to the market prior to the AIA, the requirements of the AIA must be met within two years of the respective rules coming into force.

13. Concluding remarks and recommendations for action

Whether the AI Act will live up to the high expectations placed on it remains to be seen. The regulation gives the impression that the legislator has attempted to bring an arsenal of defences into position against an enemy that it does not yet really known and of which it also does not know whether and how it will strike and with what effect.

It is emphasised that the AI Act is designed to be risk-based. This seems indeed to be the case, at least given that it remains (maybe surprisingly) soft in regulating "normal" AI applications, providing for only very few and specific "hard" rules.However, when it comes to applications that are considered to be particularly risky, it is quite comprehensive and expects a lot from providers – and it imposes obligations upon providers for which there are not yet any recognised best practices, such as data quality standards for AI models. Fortunately, these high-risk applications are defined comparatively narrowly and, above all, conclusively, even if the list may be adapted over time. Nevertheless, providers of products that are already regulated and providers in the area of critical infrastructures will have to deal with these requirements particularly intensively.

For most companies in the EU and to a lesser extent in Switzerland, the AIA will entail work, but this should not get out of hand if they have some control over where AIS is used in-house in their own products and services and those used by third parties. Above all, they will want to ensure that they do not get into the "minefields" of prohibited AIS or HRAIS. If they steer clear of these, they should be able to cope with the few remaining obligations (mainly on transparency) relatively easily, even if they are considered a "provider" because they have developed or further developed an application themselves. One exception may be the obligation to mark AI-generated content; here, suitable standards and ready-to-use solutions are apparently still lacking. It will be interesting to see what the market leaders will offer here, especially for AI-generated texts.

Swiss companies cannot avoid the AIA either, even if it only applies to them to a limited extent and, as in the case of the GDPR, it cannot be assumed that they will be the focus of the EU market surveillance authorities. It is not yet clear in all cases whether the AIA will apply to them because mistakes have been made in its drafting. However, it is to be expected that the use of AIS is covered in any case if AI output is sent to recipients in the EU intentionally or is otherwise used within the EU. If a Swiss company offers its customers in the EU market AI functions under its own name as part of its products, services or website, which it has at least partially developed itself, it is also covered. However, as long as it is not a HRAIS, the obligations are moderate.

This means that for most companies, the main effort will be to understand what AI is being used within their own organisation and in what form, so that they can react in good time if a project is moving towards one of the aforementioned minefields. When it comes to a HRAIS, companies will be particularly well advised to avoid the role of the provider and, therefore, avoid in-house developments given that the provider is subject to far more obligations than the mere deployer.

This leads to our recommendation for action: Companies should record all their own AIS and those used by third parties and assess whether and in which role (provider, deployer, distributor, etc.) they will fall under the AIA. Once this has been done, appropriate guidelines must be issued to ensure that these AIS are not used in a way that leads to a different qualification without prior assessment. Also, in cases where the AIA applies, the resulting obligations must be determined and a plan drawn up as to how these can be implemented within the specified deadlines. This recommendation applies by analogy to new projects.

This article is part of a series on the responsible use of AI in companies:

- Part 1: AI at work: The three most important points for employees

- Part 2: Popular AI tools: What about data protection?

- Part 3: AI: 11 principles – and an AI policy for employees

- Part 4: How to assess the risks of both small and large AI projects

- Part 5: AI governance in our company – who is responsible?

- Part 6: The flip side of the coin: Where we need to protect AI from attackers

- Part 7: The EU AI Act - what it means in practice for most companies

- Part 8: AI in financial institutions – opportunities and challenges (coming March 5, 2024)

- Part 9: Use of AI in marketing: Competition law pitfalls (coming March 12, 2024)

- Part 10: Copyright and AI: Responsibility of providers and users (coming March 19, 2024)

- Part 11: Fair play with AI: How sports organisations may use athlete data (coming March 26, 2024)

- Part 12: Feeding AI: How to commercialize data sets (coming April 2, 2024)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.