Key takeaways

- Criminal fines under the revised Federal Data Protection Act of up to CHF 250'000 are to be imposed primarily on an individual and not on a legal entity.

- The catalog of criminal actions that may lead to fines is expanded but is still limited.

- The requirements that the individual acted with intent and that the data subject concerned lodges a complaint continue to be a serious threshold for convictions.

- Neither indemnification agreements nor D&O insurances, but actual internal compliance processes and reporting are necessary to mitigate the exposure of individual employees.

Introduction

As of 1 September 2023, the revised Federal Act on Data Protection (revFADP) will come into force. Under the revFADP, undertakings and their employees will not only be confronted with new obligations regarding the processing of personal data (see here: https://pestalozzilaw.com/en/insights/news/legal-insights/revised-federal-act-data-protection/) but will also face criminal sanctions in case of non-compliance with certain of these obligations.

The revFADP follows the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in many aspects; however, regarding sanctions, there are some noteworthy differences.

The revFADP's Sanctions

The catalog of offences leading to criminal sanctions is extended

Unlike for the GDPR, under which almost every non-compliance can lead to administrative or criminal sanctions, the catalog of offences in the revFADP that lead to criminal sanctions is much smaller, albeit extended in comparison to the current law.

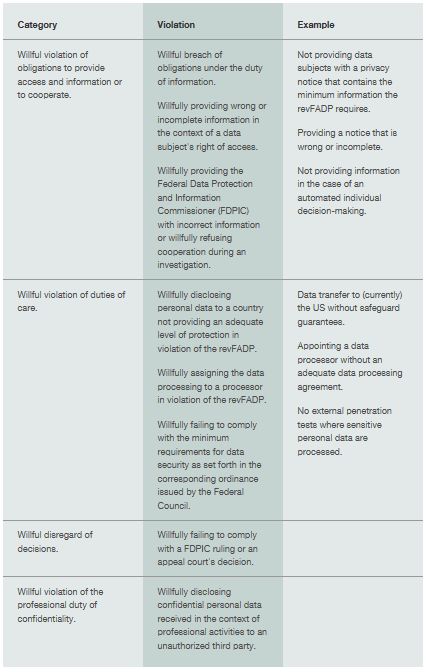

In future, the infringement of the following data protection provisions can lead to sanctions:

Other violations of the revFADP cannot be fined under the revFADP. In particular, non-compliance with the general data processing principles are not subject to criminal sanctions nor is the failure to notify the FDPIC about data security breaches.

Sanctions are higher than before

Under the revFADP, infringement of the criminal data protection provisions will be subject to a fine of up to CHF 250'000, whereas today the maximum fine is limited to CHF 10'000. Compared to the GDPR, which provides for a fine of up to EUR 20 million or four percent of an undertaking's global turnover, whichever is higher, the Swiss penalty amount may seem low. Keeping in mind that in Switzerland the fine will be imposed on individuals and not on undertakings, as in the EU, the fine's range appears in a different light.

Sanctions are (principally) directed at individuals

The aspect that Swiss law fines individuals accountable for non-compliance with certain data protection provisions makes an essential difference to the GDPR, which imposes sanctions on undertakings. Under Swiss law, however, the individual (in an undertaking) who infringed the data protection provisions punishable by fine, i.e., the individual who actually committed the violation (cf. Federal Act on Administrative Criminal Law (ACLA)), is to be held criminally liable. That individual does not necessarily need to hold a managing position. Thus, any employee managing relevant data processing activities who willfully decides to violate the revFADP, for example, by transferring data to an inadequate country, without safeguard guarantees, may be subject to criminal prosecution. Whether the violation has been committed by the individual itself or by giving another individual under its purview a corresponding instruction is not relevant. On the contrary, those who merely follow instructions or otherwise contribute to the violation in a subordinate role, cannot be fined under the revFADP.

What is worth highlighting is that the individual who has a legal obligation to prevent a violation being committed within an undertaking and who has the necessary authority to prevent such violation but fails to do so or fails to mitigate the consequences of a violation can also be fined. Possible perpetrators are company directors, employers, principals or representatives as well as corporate bodies and their members (e.g., board of directors), managers, de facto officers or liquidators. The legal obligation must refer directly to the prevention of the specific infringement (e.g., "responsibility for compliance with data protection law") or do so indirectly by referring to an obligation to protect the company's interests.

Exceptionally, following the principles of the ACLA, should the relevant fine not exceed CHF 50'000, and the investigation necessitate investigative measures out of proportion to the fine to be incurred, the authority may waive prosecution of individuals and sanction the undertaking itself to pay the fine.

Why Panic is Unnecessary but Care is Important

Only willful non-compliance is subject to sanctions

As outlined above, criminal sanctions may only be imposed on a natural person acting willfully, i.e., with intent. Only executives and other persons with a legal obligation to prevent a violation but failing to do can also be held criminally liable, again only if the underlying breach has been committed with intent. Under Swiss criminal law, a person acts willfully if he/she carries out the act in the knowledge of what he/she is doing and in accordance with his/her will. Furthermore, a person already acts willfully as soon as he/she considers the realization of the criminal act as being possible and accepts this. Hence, where an individual, although seeing the risk of the criminal success, trusts that the criminal success will not materialize, it does not meet the threshold for committing a willful crime. Willful non-compliance may, however, include cases where an individual intentionally does not want to know, for instance by willingly not investigating a matter to avoid finding out about a violation.

Prosecution mainly takes place upon complaint

Violations of the revFADP subject to criminal sanctions may only be prosecuted upon criminal complaint rather than ex officio. Any person who suffers harm due to the infringement of the criminal provisions, i.e., the data subject, is entitled to request that the person responsible for such infringement be prosecuted. It must do so within three months as of the day that the person entitled to file a complaint discovers both the violation and the identity of the suspect. Only contraventions in proceedings with FDPIC are prosecuted ex officio.

Additional procedural aspects should be considered

The FDPIC is not entitled to file a complaint but might report an offence to the competent cantonal law enforcement authorities and exercise the rights of a private claimant in the criminal proceedings. These authorities, and not the FDPIC, are responsible for enforcing the criminal provisions. This might be a difficult constellation, considering that cantonal law enforcement authorities in general do not have in depth experience with these types of questions but are entitled to take legal measures, while the FDPIC does have the experience but may not prosecute.

Finally, fines above CHF 5'000 will be registered in the judicial record but will not be visible in the private extract (which is occasionally requested in connection with job applications).

Recommendations

Whereas sanctions directly imposed by the GDPR (rather than by member state law) are considered as an administrative fine, sanctions under the revFADP are to be qualified as criminal fines; thus the undertaking may not commit to pay the fine in place of the fined individual within their company. The same holds true for classic D&O insurances, who will not cover respective criminal fines. On a practical level, this means that measures aiming to avoid the intent threshold are to be focused on. In practice, executives should consider the following:

- Verify and ensure internal processes for updating (i) data privacy notices, (ii) data processing agreements, and (iii) data security aspects.

- Verify and ensure that internal processes exist for handling of data subjects' access rights.

- Request regular reporting on all handled data access requests and data security.

- Verify and ensure adequate staffing for data protection matters.

- With delegated responsibilities, the delegating body should ensure that the person(s) charged with the task is/are fit for this task, properly instructed, and adequately supervised.

Conclusion

At least in theory, the sanctions under the revFADP will get stricter and non-compliance with the criminal law provisions in the revFADP will lead to more severe sanctions. This will now hold true for companies of all sectors, not just for banks and financial services providers who have long been accustomed to comply with specific professional confidentiality duties (e.g. Swiss bank secrecy). In contrast to the GDPR, the revFADP, however, provides for different peculiarities that might prevent the cantonal law enforcement authorities from imposing (immense) fines against individuals within a company for even the smallest non-compliance with criminal data protection provisions. Nevertheless, executives should consider stringent internal processes and reporting aimed at avoiding intentional violations of the revFADP.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.