Gone are the days when workplace safety belongs only in factories and mines. In 2023 criminal charges can and will be brought in relation to hazards and their associated risks that traverse every industry, every workplace and cannot be seen by the naked eye. Caution signs will not "cut the mustard".

Born originally from the industrial revolution and based on United Kingdom legislation harking back to the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 (sometimes known as the Factory Act), work health and safety legislative schemes have historically been focused on visible risks to physical safety.

The discovery of the harmful effects of asbestos and, more recently, diseases such as coal workers' pneumonoconiosis and silicosis have contributed to the increased awareness of not just immediate safety – falling from heights, limbs being amputated by plant and unsafe operation of machinery – but also long-term effects of work on a person's health.

Today, the workplace health and safety risks addressed by regulators extend beyond the physical, or the health effects, to the psychological. It is a real and increasing possibility that Australian organisations and their workers may face criminal charges under work health and safety legislation for failing to control hazards and their associated risks that are psychological in nature and not necessarily visible to the human eye.

Specific regulations have been introduced in several Australian jurisdictions to deal with psychosocial hazards. Examples of psychosocial hazards include job demands, low job control, poor support, lack of role clarity, poor organisational change management, inadequate reward and recognition and poor organisational justice.

The increased focus of regulators on psychosocial risks poses unique challenges for duty holders, not in the least because it is difficult to put in place measures to control risk that you cannot see, but also because the nature of the hazards mean that workers, or others, may be affected by those hazards in widely varying ways, and this may also be different for the same worker at different times.

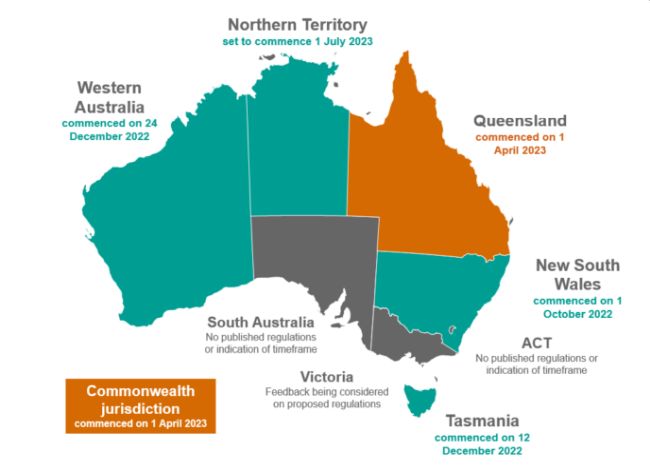

The latest jurisdiction to adopt the set of model regulations published by Safe Work Australia was the Northern Territory, announcing that its regulations will commence on 1 July 2023, joining New South Wales, Western Australia, Tasmania, Queensland and the Commonwealth where specific psychosocial regulations have already commenced.

The regulations in Queensland and the Commonwealth differ from the model regulations, which have been adopted in New South Wales, Western Australia, Tasmania and will be adopted in the Northern Territory. In the model regulations, an exception is created so that persons conducting a business or undertaking (PCBUs) do not need to apply the hierarchy of controls when determining control measures for psychosocial risk. These jurisdictions are shown in green on the map. The Queensland and Commonwealth jurisdictions, coloured orange on the map, have amended the model regulations to remove this exception, meaning duty holders there are subject to a more onerous regulation that requires they apply the hierarchy of control measures, even to psychosocial risks.

It must be noted that before these specific psychosocial regulations, PCBUs already held a duty to control psychosocial risks, as they do with any other types of risk, as part of their primary duty of care to ensure the health and safety of workers and others, so far as is reasonably practicable. While the new regulations don't create any new duties, they do:

- define the terms 'psychosocial risk' and 'psychosocial hazard';

- call out psychosocial risk specifically as something that falls within the general health and safety duty, whether or not that risk also causes a physical risk; and

- prescribe matters that a PCBU must take into account when determining control measures to implement.

It is clear that regulators are taking this area of work health and safety seriously, regardless of the industry. Examples of these issues being considered, even prior to the introduction of specific regulations, have arisen in consulting and audit firms, the university sector, the legal profession, local councils, retailers, mining, and even safety regulators. These industries have faced public scrutiny, regulatory action, and in the case of safety regulators, parliamentary inquiries, for allegedly failing to manage psychosocial hazards adequately. The legal and regulatory risk in this area is real, not theoretical.

As we have passed the six-month mark since the first of the psychosocial regulations was introduced, with all the associated commentary and guidance, it is clear that the following should be on the agenda of every organisation's leadership team:

- Take a proactive approach – like any hazard and associated risk, psychosocial hazards and risks require a risk assessment that aligns with the principles of WHS risk management.

- Policies and procedures for inappropriate workplace behaviours are important, as is the training/information/instruction and implementation in respect of these measures.

- Effective leadership is critical. At a fundamental level, this emerging area of increased regulation is intended to effect behavioural and cultural change within Australian working life and workplaces. Leaders have to be engaged and demonstrate meaningful commitments to managing psychosocial hazards and risks.

- There are no "off-the-shelf solutions". A specific and tailored approach is required.

- Consultation with workers is key.

- Focus on prevention rather than treatment.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.