Welcome to Volume 1 of Proskauer's Restrictive Covenants, Trade Secret & Unfair Competition Update. In this highly competitive, knowledge-driven global marketplace, a company's ability to protect its trade secrets, human capital and client relationships has become critical to its success and survival. Below is a deeper dive into the latest developments and trends impacting non-compete and trade secret law today.

Edited by Joseph C. O'Keefe and Steven J. Pearlman

Low Wage and Employee Classification Limits on Non-Compete Agreements

Originally published on November 18, 2021 and updated as of January 27, 2023.

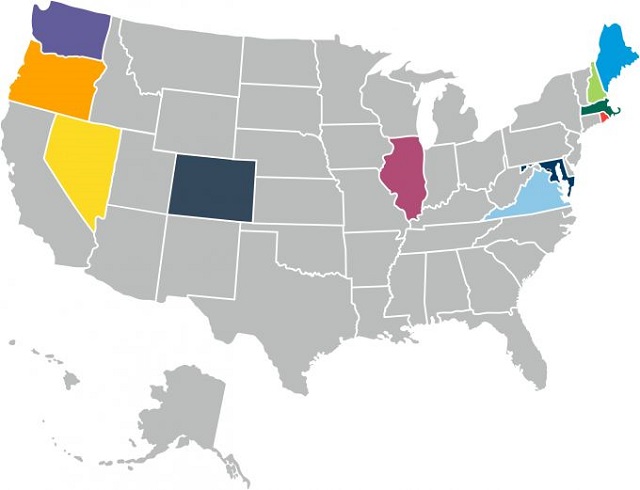

Over the past few years, states across the country have sought to limit or reduce the use of employee non-compete agreements. While some have imposed outright bans on such agreements, many more have passed laws that narrow the scope or classification of an employee who may be subject to a non-compete.

A common restriction is to prohibit the use of non-competes for employees who earn below a certain threshold – e.g., annual compensation, hourly wage, percentage of poverty level, or FLSA status. Employers operating in multiple states face a patchwork of regulations and need to keep their non-compete thresholds up to date. Setting calendar reminders for the annual wage updates and following the Proskauer Non-Compete and Trade Secrets page are the right steps to keep agreements compliant as the patchwork evolves.

Click map to download printable PDF

Colorado

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning less than $112,500 per year. Customer non-solicits prohibited for employees earning less than $67,500 per year.

Illinois

Non-competes prohibited for less than $75,000 per year. Non-solicits prohibited for employees earning less than $45,000 per year.

Maine

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning wages at or below 400% of the federal poverty level, or $58,320 per year.

Maryland

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning less than or equal to $15 per hour or $31,200 per year.

Massachusetts

Non-competes prohibited for: (i) non- exempt employees; (ii) undergraduate or graduate students participating in internships or short-term employment; employees that have been terminated without cause or laid off; and employees under the age of 18.

New Hampshire

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning an hourly wage less than or equal to 200% of the federal minimum wage ($14.50 per hour or $30,160 per year); or (ii) less than or equal to 200% of the tipped minimum wage in the state.

Nevada

Non-competes prohibited for employees who are paid solely on an hourly wage basis, exclusive of tips or gratuities.

Oregon

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning less than or equal to $100,533* per year.

Rhode Island

Non-competes prohibited for: (i) non- exempt employees; (ii) undergraduate or graduate students participating in internships or short-term employment; employees under the age of 19; and employees whose average annual earnings (excluding overtime, Sunday, or holiday premiums) are less than 250% of the federal poverty level, or $36,450 per year.

Virginia

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning less than Virginia's average weekly wage: $1,343 per week or $69,836 per year.

Washington

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning less than $116,593.18 per year, and independent contractors earning less than $291,482.95 per year.

Washington, DC

Non-competes prohibited for employees earning less than $150,000 per year.

*This number is current as of January 1, 2022.

Advanced Notice: Continuing Trends in State Restrictive Covenant Legislation

In recent years, federal and state lawmakers have been increasingly eager to limit employers' ability to enter into restrictive covenant agreements with their employees. A growing trend is legislation requiring that employers give individuals advance notice (or a "consideration period") before the employee can sign a restrictive covenant agreement. Prior to 2022, only five states (Oregon, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maine, and Washington) had such laws on the books. That number almost doubled this past year, as Illinois, Colorado, and the District of Columbia enacted statutes requiring varying degrees of advance notice.

I. Illinois

Under the Freedom to Work Act, effective as of January 1, 2022, Illinois employers must advise prospective and current employees in writing to consult with an attorney before entering any agreement that contains either a covenant not to compete or a covenant not to solicit. 820 ILCS 90. Furthermore, the employer must provide the individual with at least fourteen calendar days to review the restrictive covenant before signing it. Although an employee may voluntarily elect to sign the restrictive covenant agreement before the expiration of the 14-day consideration period, the entire period must still be provided to the individual.

The Illinois Freedom to Work Act goes on to define "adequate consideration" for restrictive covenant provisions in such a way that, even if the employer follows all of these steps, the restrictive covenants will be rendered unenforceable unless the employee works for the employer for at least two years after signing the agreement containing the non-compete or non-solicit provision. Before this legislation, Illinois statute did not specify a set length of tenure as a precondition for non-compete agreements.

II. Colorado

Effective as of August 10, 2022, before entering into a non-compete agreement with either a prospective or current employee, Colorado employers must provide the individual with advance "notice of the covenant not to compete" and the "terms of the covenant not to compete." Colo. Rev. Stat. § 8-2-113(4).

For prospective employees, the employer must provide the individual with the notice, and the terms of the proposed non-compete beforethe prospective employee even accepts an offer of employment.

For current employees, the employer must provide the employee with the notice and the terms of the proposed non-compete at least fourteen days before the earlier of (a) the effective date of the covenant; or (b) the effective date of any additional compensation or change in terms and conditions of employment that would provide consideration for the covenant.

In both cases, the required notice of the non-compete must be provided to the employee or prospective employee in "clear and conspicuous terms" and must be signed by the worker. Although it appears that employees should be able to sign the notice and the non-compete agreement before the entire consideration period has elapsed, the non-compete would still not be effective until fourteen days from the date of the notice.

The statute's required notice must be presented in a separate document from the actual non-compete agreement and signed by the employee. This means that employers must obtain two signed documents to effectuate a non-compete – first, the notice document, followed by the agreement containing the non-compete provision itself.

III. Washington, D.C.

After years of delays and amendments, the District of Columbia Ban on Non-Compete Agreements Amendment Act of 2020 finally went into effect on October 1, 2022, as modified by the District of Columbia Non-Compete Clarification Amendment Act of 2022. D.C. Law 24-175. While the statute prohibits most non-compete agreements, unlike the prior iterations of the proposed legislation, the implemented version allows employers to continue to utilize such agreements for highly compensated individuals and some additional excluded categories of employees.

To make permissible non-compete agreements enforceable, employers are now required to provide a copy of the non-compete agreement, in writing, to a prospective employee at least fourteen days before the individual commences work for the employer. For employers seeking to bind current employees to a new non-compete agreement, the employer is also required to provide a copy of the non-compete, in writing, to that individual at least fourteen days before the employee is required to execute it.

Unlike other jurisdictions, the D.C. statute also delineates specific language that must be included in the notice to current and prospective employees, along with a copy of the non-compete agreement. The language that must be included in the notices is as follows:

The District of Columbia Ban on Non-Compete Agreements Amendment Act of 2020 limits the use of non-compete agreements. It allows employers to request non-compete agreements from "highly compensated employees" under certain conditions. [Name of employer] has determined that you are a highly compensated employee. For more information about the Ban on Non-Compete Agreements Amendment Act of 2020, contact the District of Columbia Department of Employment Services (DOES).

IV. Existing Advance Notice Requirements

Although the new statutory requirements enacted in 2022 continue, and build upon, the trend of making advance notice a prerequisite for the enforcement of non-compete agreements, the five states below were early adopters of such policies:

- Oregon (effective 2007): Prospective employees must be informed, in writing, at least two weeks before their first day of work that a non-compete is a requirement of employment. For existing employees, a new non-compete agreement will only be enforceable if accompanied by a bona fide promotion. ORS 653.295(1)(a).

- New Hampshire (effective July 14, 2012): Under New Hampshire law, an employer must give prospective employees a copy of a non-compete agreement before acceptance of an offer of employment. NH RSA § 275:70.

- Massachusetts (effective October 1, 2018): Non-compete agreements must be provided to prospective employees at least ten business days before the commencement of employment or before a formal offer is extended, whichever comes earlier. For existing employees, the employer must provide notice of the non-compete agreement at least ten business days before the agreement becomes effective. MGL c.149, § 24L(b)(i)-(ii).

- Maine (effective September 18, 2019): Employees must receive notice of the non-compete agreement before an offer of employment and a copy of the agreement at least three business days before the deadline to sign. 26 MRSA §599-A(4).

- Washington (effective January 1, 2020): Employers must disclose the terms of a non-competition covenant to a prospective employee no later than the acceptance of an offer of employment. For existing employees, non-competition covenant is only enforceable due to a change in the employee's compensation and the employer must specifically disclose that the covenant may be enforceable against the employee in the future. RCW 49.62.020.

V. Pending Advance Notice Requirement Legislation

Looking ahead to 2023, another state is already considering adding an advance notice requirement for non-compete agreements: New Jersey. On May 19, 2022, the New Jersey General Assembly Labor Committee voted to advance Assembly Bill 3715 ("A3715") to the entire legislature.

If passed, A3715 would impose numerous harsh limitations on restrictive covenants, including a requirement that prospective employees must receive terms of any restrictive covenant agreement by the earlier of a formal offer of employment or 30 business days before the individual commences employment with the company. If the individual is already employed, the employer must provide the individual with the terms of the restrictive covenant at least 30 days before the agreement becomes effective.

Furthermore, the bill provides that an employer must notify a former employee, in writing, whether it intends to enforce the restrictive covenant agreement no later than ten days after the termination of the employment relationship.

Under the proposed legislation, restrictive covenants executed after adoption of A3715 would be deemed null and void if an employer fails to provide any of the above notices. At this stage, it is unclear whether A3715 – which has yet to receive a vote from the entire General Assembly – will advance further. Legislation of this nature, however, seems to be gaining steam and getting more common with each passing year.

As more and more states enact legislation requiring advance notice for restrictive covenant agreements, it would benefit employers to continually monitor legal developments in this area of law to ensure full compliance. To avoid costly and avoidable pitfalls, employers must be aware of the law in the states they operate in and give prospective and current employees the requisite advance notice to review and consider restrictive covenant agreements.

Lessons Learned From 2022's Trade Secret Verdicts

Before closing the book on 2022, we look back at the most significant verdicts issued in trade secret trials this past year. In 2022, several juries awarded extraordinary verdicts to plaintiffs. These verdicts suggest a growing trend in damages theories and illustrate the importance of expert testimony in both the prosecution and defense of trade secret misappropriation cases. The cases also highlight considerations related to the scope of the definitions of trade secrets alleged starting at the outset of a case. For companies pursuing or defending against trade secret actions in 2023, looking to these verdicts and the theories that helped persuade a jury or judge can help guide strategy from the outset of the case through trial.

1. Sky-High Verdicts Reveal a Growing Trend in Damages Theories

2022 saw substantial verdicts in trade secret actions across various industries. Most noteworthy was the verdict in Appian Corp. v. Pegasystems Inc., No. 2020-07216 (Va. Cir. Ct. Fairfax Cty. May 9, 2022), in which the jury awarded a staggering $2 billion in favor of plaintiff Appian for the misappropriation of trade secrets in violation of the Virginia Trade Secrets Act and Virginia Computer Crimes Act, in addition to willful and malicious misappropriation.

Appian alleged that Pegasystems conspired with a former Appian employee who possessed a copy of Appian's software to disclose the former employee's knowledge of the software. Pegasystems then used the information to create its own product to compete with Appian. Appian presented evidence that Pegasystems had used an individual they referred to as "our spy" to glean secrets from a trial of Appian's software.

Other sizable trade secrets verdicts from 2022 include:

- Versata Software Inc. v. Ford Motor Co., No. 2:15-cv-10628 (E.D. Mich. Oct. 26, 2022), in which the jury awarded Versata Software $105 million for its breach of contract and misappropriation of trade secrets claims against Ford Motor Co. on the theory that Ford had misappropriated software developed by Versata utilized in managing how Ford vehicles are assembled;

- Coda Development SRO v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., No. 5:15-cv-1572 (N.D. Ohio Sept. 19, 2022), in which the jury awarded Coda Development $64 million for the misappropriation of trade secrets involving self-inflating tires after Coda Development and Goodyear had discussed a potential collaboration;

- Comet Technologies USA Inc. v. XP Power LLC, No. 20-cv-06408(N.D. Cal. Mar. 23, 2022), in which Comet Technologies was awarded $40 million for the misappropriation of trade secrets related to the manufacture of semiconductor chips, which Comet alleged occurred after XP hired away Comet employees who were aware of the proprietary technology; and

- Epic Systems Corp. v. Tata Consultancy Services, Ltd., No. 14-cv-748 (W.D. Wisc. July 1, 2022), in which Epic Systems was awarded $940 million for the misappropriation of its trade secrets. The company had also introduced evidence that a Tata Consultancy employee had used fraudulent credentials to download information from Epic Systems' proprietary systems. The verdict was ultimately remitted to $280 million following the resolution of Tata Consultancy's appeals.

These verdicts may be a harbinger of rising damages awards levied by juries for claims of trade secret misappropriation.

On top of their size, what is particularly noteworthy about some of these verdicts – especially the Appian Corp. and Comet Technologies verdicts – is that the jury relied on a particular unjust enrichment theory to award damages, a theory that is available under the Defend Trade Secrets Act ("DTSA") and some state statutes. This theory focuses on avoided development costs.

Indeed, over the past year, courts have increased recognition of this remedy. Companies often spend years and thousands or even millions of dollars developing their trade secrets. When these trade secrets are stolen, either by a former employee or trusted contractor or vendor, the question often arises whether the misappropriating party can be held liable for the trade secret owner's sunk costs of creating and developing the trade secrets. The answer varies by jurisdiction, but courts increasingly have said "yes."

The DTSA allows for "damages for any unjust enrichment caused by the misappropriation of the trade secret that is not addressed in computing damages for actual loss." 18 U.S.C. § 1836(b)(2). The Uniform Trade Secrets Act ("UTSA"), which has been adopted in every U.S. state except New York and North Carolina, includes nearly identical language, allowing damages for "the unjust enrichment caused by misappropriation that is not taken into account in computing damages for actual loss."

Unjust enrichment in the context of trade secret misappropriation is often called "avoided costs" – i.e., the costs that the misappropriator has avoided by taking the completed trade secret. Under this theory, parties found liable for trade secret misappropriation would be liable for costs they "avoided" by misappropriating the trade secret in lieu of developing the trade secret themselves. Wide acceptance of the "avoided costs" remedy would add more teeth to an area of law in which actual damages have been difficult to prove.

It would be premature to say that courts across the United States have widely recognized the avoided costs theory of recovery. However, the theory is gaining traction. For example, in Appian Corp., Appian promulgated only this unjust enrichment theory of damages in the trial, which Pegasystems countered by asserting that it had not been profitable during the relevant time period and, therefore, had not been unjustly enriched. Given the verdict's size, the jury appeared to reject Pegasystems' argument.

A similar theory was promulgated in Comet Technologies, in which Comet Technologies obtained damages under an unjust enrichment theory that XP had a "head start" in developing equipment used to manufacture semiconductor chips.

In addition, a district court in California recently indicated its acceptance of the remedy. In MedImpact Healthcare Sys., Inc. v. IQVIA Inc., No. 19-cv-1865, 2022 WL 6281793, at *7 (S.D. Cal. Oct. 7, 2022), the plaintiff was denied "avoided costs" in arbitration over a trade secrets case. However, the district court held that "avoided costs" may still be an appropriate remedy for post-arbitration continuing conduct: "[I]n view of the ongoing nature of the alleged misappropriation, unjust enrichment may still a viable theory of damages under the DTSA and CUTSA for post-arbitration conduct."

In a separate ruling in the same case, the court noted that "[t]he Ninth Circuit has not yet ruled on whether avoided costs are available as damages for unjust enrichment under the DTSA but other jurisdictions have recognized that avoided costs of developing a trade secret are recoverable for unjust enrichment under the DTSA and state law counterparts." MedImpact, 2022 WL 5460971, at *5.

The court pointed to cases in other jurisdictions, such as GlobeRanger Corp. v. Software AG United States of Am., Inc., 836 F.3d 477, 499 (5th Cir. 2016) ("The costs a plaintiff spent in development ... can be a proxy for the costs that the defendant saved"), and Syntel Sterling Best Shores Mauritius Ltd. v. TriZetto Grp., Inc., No. 15 CIV. 211 (LGS), 2021 WL 1553926, at *6 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 20, 2021) ("Avoided costs damages are proper under the DTSA as a matter of law.").

Although unjust enrichment verdicts are often appealed, it is noteworthy that, in November 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit and U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit both upheld multi-million-dollar trade secret verdicts and awards based in part on unjust enrichment theories. PPG Indus. v. Jiangsu Tie Mao Glass Co., No. 21-2288, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 24411 (3d Cir. Aug. 30, 2022); Caudill Seed & Warehouse Co. v. Jarrow Formulas, Inc., 53 F.4th 368 (6th Cir. 2022).

Defendants in trade secret misappropriation actions should therefore proceed with caution given that unjust enrichment theories may become increasingly accepted by appellate courts and juries, despite some state courts previously rejecting the theory. See E.J. Brooks Co. v. Cambridge Security Seals, No. 26, 2018 BL 157167 (N.Y. May 3, 2018) (holding that compensatory damages for misappropriation of trade secrets are limited to the plaintiff's losses and do not include development costs saved by the defendant or additional damages for unjust enrichment theories).

Even with the split in authority that exists now, the increased acceptance of the "avoided costs" remedy is likely to be accompanied by an increase in litigation surrounding the methods for calculating these costs. Research and development costs are rarely finite or easily calculable, and it may be difficult to attribute particular costs to particular trade secrets. The difficulty and cost in litigating over this issue can be mitigated if businesses retain records accounting for the research and development costs for their most valuable trade secrets.

2. Litigants in Trade Secret Matters Should Consider Utilizing Expert Testimony for Damages Calculation

It is often the case that, due to the complexity of damages calculations, litigants in trade secret matters rely upon expert testimony. Indeed, experts in misappropriation cases involving unjust enrichment often assist by providing testimony comparing any benefit conferred by the alleged misappropriation versus what might have occurred if the defendant had acquired the trade secret through lawful means.

Trade secret verdicts from 2022 provide a reminder of the potential importance of such testimony and its possible impact on a jury, as expert testimony helped lead to some of the largest verdicts in 2022.

For example, in the cases cited above that relied on an unjust enrichment theory, expert testimony regarding the costs saved by the defendants ultimately helped establish the damages to be appropriately proportioned based on the unjust enrichment. In Comet Technologies USA Inc. v. XP Power LLC, Comet's expert witness testified that unjust enrichment damages should be measured by looking at the cost the defendant had saved because the defendant's products would be introduced in the future. No. 20-cv-06408(N.D. Cal. Oct. 28, 2022). The jury credited this explanation, as it awarded Comet $20 million in unjust enrichment damages (as well as $20 million in punitive damages).

3. Changing the Definition of Trade Secrets Throughout Litigation May Compromise a Plaintiff's Case

An important decision for a plaintiff filing a trade secret matter is how narrowly to define the trade secrets in the complaint. While plaintiffs are often hesitant to waive potential claims and unnecessarily narrow the scope of the matter, failing to identify trade secrets with sufficient specificity can put claims at risk of early dismissal. See, e.g., You Map Inc. v. Snap Inc., No. 20-cv-162, 2021 WL 106498 (D. Del. Jan. 12, 2021), report and recommendation adopted, No. 20-cv-162, 2021 WL 327388 (D. Del. Feb. 1, 2021) ("There are at least two problems with Plaintiff's current position. The first is that Plaintiff must adequately identify the trade secrets in the Complaint. If the claimed trade secrets are source code or software algorithms (or something else entirely), Plaintiff needs to specify that in the Complaint. The second problem is that Plaintiff's failure to adequately identify the trade secrets renders the Court unable to determine if the Complaint plausibly alleges that Defendants misappropriated them.").

However, one verdict from 2022 flagged another potential risk to plaintiffs in failing to sufficiently narrow the trade secrets at issue in a misappropriation claim. In Masimo Corp. v. True Wearables, Inc., No. 8:18-cv-02001 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 7, 2022), the court found after a bench trial that a former executive had misappropriated trade secrets and used them in products of his new company in violation of the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act. But in assessing whether an award of attorney's fees was appropriate in light of the ruling, the court found that the plaintiffs "drove the trajectory of this case in a manner that required both parties to spend a significant amount on attorney's fees as they prepared for trial. Over three years after the case was filed, at the time of trial, Plaintiffs had whittled their intellectual property case down to a handful of trade secrets and a single patent claim. Further, Plaintiffs prevailed on only a select number of their misappropriation theories, and did not prevail on their patent infringement claim. Against this backdrop, the Court [found] it would be inequitable to award Plaintiffs attorney's fees." Id. at 66.

The Masimo ruling serves as a caution that plaintiffs who fail to sufficiently define the trade secrets at issue at the outset of a case or who change or narrow the definition of the trade secrets throughout litigation may jeopardize their ability to obtain attorneys' fees under the various trade secret statutes after a verdict is rendered. Before proceeding to court, putative plaintiffs should carefully consider the benefits and drawbacks of the definitions of the trade secrets included in a complaint.

Developments in FTC Scrutiny of Non-Competes

On July 9, 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order on promoting competition in the economy, which encouraged the Federal Trade Commission ("FTC") to "curtail the unfair use of non-compete clauses and other clauses or agreements that may unfairly limit worker mobility." On January 5, 2023, the FTC proposed a new rule imposing an almost complete ban on the use of non-competes. Even prior to that proposal, the FTC's recent actions signaled that increased scrutiny of non-competes and other restraints on worker mobility would be forthcoming.

As detailed below, the FTC previously issued formal guidance, both jointly with the Department of Justice ("DOJ"), and individually, to expand the scope of enforcement under federal antitrust laws. The FTC's FY 2022-2026 Strategic Plan further underscored its upcoming focus on anti-competitive practices. In addition, the FTC has targeted non-competes in several recent enforcement actions.

Employers have a pressing need to evaluate their non-compete agreements in light of the heightened regulatory risks signaled by these recent developments.

DOJ and FTC Issue Joint Antitrust Guidance for Human Resources Professionals

The recent federal focus on non-competes was signaled as early as October 2016, when the FTC and DOJ issued joint antitrust guidance directed at human resources professionals. The guidance set forth the agencies' position that businesses that compete to hire or retain the same group of employees are competitors, regardless of whether they make the same products or provide the same services, and it is unlawful for such businesses to agree, expressly, or implicitly, not to compete with each other.

Notably, the guidance asserts that wage-fixing agreements (in which competitors agree to set employee compensation at certain levels) and no-poach agreements (in which competitors agree not to solicit or hire each other's employees) are "naked" restraints on trade and per se illegal under the antitrust laws. The DOJ announced its intention to prosecute such agreements in criminal actions, not just civil actions.

The DOJ's heightened enforcement is consistent with the Executive Order's encouragement of agencies to "coordinate their efforts," particularly with respect to "concurrent [DOJ] or FTC oversight activities under the Sherman Act or Clayton Act." Since 2016, the DOJ has sought to enforce the new per se rule announced in the joint guidance in several criminal indictments against both employers and individuals, and remains determined.

For example, in April 2022, a Colorado jury acquitted DaVita Inc.and its former CEO of all charges brought by the DOJ alleging that it formed a conspiracy with three other owners/operators of outpatient medical facilities to avoid soliciting each other's senior-level employees. In January 2022, the court ruled that such non-solicitation agreements could not be treated as a new category of restraint subject to per se treatment under the Sherman Act, as the DOJ argued, but may fall under a preexisting category of per se treatment for attempts at market allocation. United States v. DaVita Inc., No. 1:21-CR-00229-RBJ, 2022 WL 266759 (D. Colo. Jan. 28, 2022). Accordingly, at trial, the DOJ was required to prove that the companies entered into the non-solicitation agreements, and that they did so knowingly with the intent of allocating the market for senior executives and employees between themselves. The jury found that the DOJ did not satisfy this high standard.

Undeterred, however, the DOJ has continued to press criminal indictments in similar cases. See, e.g., U.S. v. Patel, No. 3:21-CR-220 (VAB), 2022 WL 17404509 (D. Conn. Dec. 2, 2022).

FTC's FY 2022-2026 Strategic Plan Includes Goals Aimed at Non-Competes

On August 26, 2022, the FTC published its 5-year strategic plan which identified several goals related to non-competes. First, under its Objective 2.1 to "identify, investigate, and take actions against anti-competitive mergers and business practices," the FTC listed as one "strategy," to "increase use of provisions to improve worker mobility including restricting the use of non-compete provisions."

Second, under its Objective 2.2 to "engage in research, advocacy, and outreach to promote public awareness and understanding of fair competition and its benefits," the FTC identified its intention to "study and investigate the impact on worker wages and benefits from merger and nonmerger conduct, as well as non-compete and other potentially unfair contractual terms resulting from power asymmetries between workers and employers."

FTC Issues Policy Statement Expanding Its Enforcement Authority Under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act

On November 10, 2022, the FTC issued a "Policy Statement Regarding the Scope of Unfair Methods of Competition Under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act" (the "Policy Statement"). The Policy Statement announced a significant expansion of the FTC's enforcement authority, intended, as FTC Chair Lina Khan explained to the Wall Street Journal, to "open the door to more legal challenges against businesses engaging in alleged coercive or deceptive conduct that undermines competition."

As one of the most substantial of the FTC's recent actions, the Policy Statement was another step toward the FTC's close examination of anti-competitive practices under the current administration.

Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act ("Section 5") broadly prohibits "unfair methods of competition in or affecting commerce." Although the FTC has historically assessed violations of Section 5 on a case-by-case basis, in 2015, the FTC issued a brief Statement of Enforcement Principles Regarding "Unfair Methods of Competition" Under Section 5 of the FTC Act (the "2015 Statement"), which was intended to align the FTC's enforcement of Section 5 with other federal antitrust laws. The FTC stated that it would be "less likely" to assert a standalone Section 5 claim "if enforcement of the Sherman or Clayton Act is sufficient to address the competitive harm."

The Policy Statement built on the FTC's rejection, earlier last year, of the 2015 Statement by setting forth new "general principles" under which, moving forward, the FTC would evaluate whether conduct violates Section 5. Notably, under the Policy Statement, a Section 5 violation may be found even where the conduct does not directly cause actual harm to the consumers, workers, or other market participants in the matter at issue, but reduces competition "in the aggregate" along with other employers engaging in similar conduct or as "the cumulative effect of a variety of different practices."

Thus, employers may face potential exposure under Section 5 even for conduct that would not be actionable under the Sherman Act, where the typical "rule of reason" inquiry involves an intensely factual assessment that considers any associated efficiencies and business justifications.

FTC Targets Non-Competes in Recent Enforcement Actions

In June 2022, the FTC challenged an acquisition by Arko Corporation ("Arko") and its subsidiaries of 60 gasoline and diesel fuel outlets from a competitor, Corrigan Oil Company ("Corrigan"), due to specific non-compete provisions included in the asset purchase agreement.

The FTC alleged that the non-compete provisions violated antitrust laws by reducing (or eliminating) Arko's competitors in market territories throughout Michigan and Ohio, and lacked any "reasonable procompetitive justification" for their application to 190 locations unrelated to the transaction.

Arko agreed to a Consent Agreement and Decision and Order which, among other conditions, (1) excluded the 190 locations from the non-compete provisions; (2) substantially restricted the duration and geographic scope of the non-compete; and (3) limited Arko's ability to enter into future non-competition provisions that would restrict competition in areas other than those surrounding an acquired location.

Traditionally, non-compete provisions in the context of mergers and acquisitions have been subjected to less scrutiny than similar provisions in employment contracts due to the buyer's legitimate business interest in protecting the customer "goodwill" and relationships acquired in the transaction. See, e.g., E.T. Products, LLC v. D.E. Miller Holdings, Inc., 872 F.3d 464 (7th Cir. 2017).

However, the FTC's action against Arko, as reflected in FTC Chair Lina Khan's accompanying statement, indicates the FTC plans to scrutinize non-competes even in such contexts, to ensure they remain "appropriately limited in geographic scope and duration" particularly if the transaction is between parties who will "remain competitors in other markets."

On January 4, 2023, the FTC invoked its recently expanded Section 5 authority and brought actions against three companies to halt their allegedly unlawful use of non-competes. The FTC asserted that Prudential Security, Inc., and Prudential Command, Inc. (together, "Prudential") required the security guards whom they employed to sign non-competes prohibiting them from working for a competing business within 100 miles of their job site for two years after leaving their employment. The FTC also objected to liquidated damages provisions in Prudential's agreements which required the employees to pay $100,000 for any conduct that violated their non-competes.

The FTC also asserted actions against the two largest manufacturers of glass food and beverage containers in the United States, O-I Glass, Inc., and Ardagh Group S.A. The actions asserted that both manufacturers imposed one-to-two year non-competes on thousands of workers who worked in a variety of roles, including glass production, engineering, and quality assurance. According to the FTC, these non-competes had the effect of locking up highly specialized workers and reducing labor mobility in a highly-concentrated sector of the economy.

In each of these actions, the FTC ordered the company to void the challenged non-competes and notify past, present, and future employees that they may freely seek other employment following separation.

These recent enforcement actions represent the FTC's novel effort to use its Section 5 authority to go beyond the bounds of traditional antitrust laws, as foreshadowed and outlined in the Policy Statement. It is a telling sign of the FTC's future expansive enforcement of Section 5.

FTC Proposes New Rule Banning Non-Competes

On January 5, 2023, the FTC proposed a sweeping new rule which would impose a near-complete ban on the use of non-competes. The rule will undergo a period of public comment and, as currently drafted, would require compliance 180 days after a final version is published.

The proposed rule defines a non-compete clause as "a contractual term between an employer and a worker that prevents the worker from seeking or accepting employment with a person, or operating a business, after the conclusion of the worker's employment with the employer." Under this definition, the proposed rule would not include restraints during employment, nor would it include other types of common restrictions such as confidentiality agreements or non-solicitation agreements.

However, under the proposed rule's "functional test," these other restrictions may be prohibited if they are drafted so broadly as to have the same effect as a non-compete.

Notably, the proposed rule's definition of the term "worker" would include interns, volunteers, independent contractors, and gig economy workers, regardless of how such individuals are classified under federal or state labor laws.

The proposed rule also requires employers to rescind existing non-compete agreements and provide current and former employees with written notices stating that their non-competes are no longer effective. Employers may satisfy this requirement by using the model notice language included in the rule.

Finally, the proposed rule establishes a narrow exception to its prohibitions for non-competes arising in the sale-of-business context. Non-competes would be permitted only when entered into by an individual who holds at least a 25% ownership interest in the business entity to be sold.

The proposed rule is expected to draw extensive comments from stakeholders, who may propose different standards for low-wage workers, as compared with senior executives or highly paid and highly skilled workers. Moreover, legal challenges to the FTC's authority to issue the proposed rule are inevitable, and it remains to be seen whether the proposed rule will survive judicial scrutiny.

For more details on the FTC's proposed rule, please see our blog post on Law and the Workplace, available here.

As highlighted by its recent actions, since President Biden's Executive Order the FTC has moved aggressively to expand its authority and rein in the use of non-competes as an anti-competitive practice. Though the courts have yet to weigh in on whether the FTC has overstepped its authority, in light of the FTC's latest actions, employers should carefully review their non-competes.

Restrictive Covenants, Trade Secret & Unfair Competition Update

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.